Headlines, 2012: “Next time you’re hiring, forget personality tests, just check out the applicant’s Facebook profile instead.” – “Stephanie Watanabe spent nearly four hours Thursday night unfriending about 700 of her Facebook friends—and she isn’t done yet” – “Facebook apology or jail time: Ohio man gets to choose” – “Study: Facebook users getting less friendly” – “Women tend to have stronger feelings regarding who has access to their personal information” (Mary Madden) – “All dressed up and no place to go” (Wall Street Journal) – “I’m making more of an effort to be social these days, because I don’t want to be alone, and I want to meet people” (Cindy Sherman) – “30 percent posted updates that met the American Psychiatric Association’s criteria for a symptom of depression, reporting feelings of worthlessness or hopelessness, insomnia or sleeping too much, and difficulty concentrating” – Control your patients: “Do you hire someone in the clinic to look at Facebook all day?” Dr. Moreno asked. “That’s not practical and borders on creepy.” – “Hunt for Berlin police officer pictured giving Nazi salute on Facebook” – “15-year-old takes to Facebook to curse and complain about her parents. The disgusted father later blasts her laptop with a gun.”

The use of the word “social” in the context of information technology goes back to the very beginnings of cybernetics. It later pops up in the 1980s context of “groupware.” The recent materialist school of Friedrich Kittler and others dismissed the use of the word “social” as irrelevant fluff—what computers do is calculate, they do not interfere in human relations. Holistic hippies, on the other hand, have ignored this cynical machine knowledge and have advanced a positive, humanistic view that emphasizes computers as tools for personal liberation. This individualistic emphasis on interface design, usability, and so on was initially matched with an interest in the community aspect of computer networking. Before the “dot-com” venture capitalist takeover of the field in the second half of the 1990s, progressive computing was primarily seen as a tool for collaboration among people.

In a chapter entitled “How Computer Networks Became Social,” Sydney media theorist Chris Chesher maps out the historical development of computer networks, from sociometry and social network analysis—an “offline” science (and a field of study that goes back to the 1930s) that examines the dynamics of human networks—to Granowetter’s theory of the strengths of weak links in 1973, to Castells’s The Network Society in 1996, to the current mapping efforts of the techno-scientists that gather under the umbrella of Actor Network Theory.1 The conceptual leap relevant here concerns the move from groups, lists, forums, and communities to the emphasis on empowering loosely connected individuals in networks. This shift happened during the neoliberal 1990s and was facilitated by growing computing power, storage capacity, and internet bandwidth, as well as easier interfaces on smaller and smaller (mobile) devices. This is where we enter the Empire of the Social. It must also be said that “the social” could only become technical, and become so successful, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when state communism no longer posed a (military) threat to free-market capitalism.

If we want to answer the question of what the “social” in today’s “social media” really means, a starting point could be the notion of the disappearance of the social as described by Jean Baudrillard, the French sociologist who theorized the changing role of the subject as consumer. According to Baudrillard, at some point the social lost its historical role and imploded into the media. If the social is no longer the once dangerous mix of politicized proletarians, of the frustrated, unemployed, and dirty clochards that hang out on the streets waiting for the next opportunity to revolt under whatever banner, then how do social elements manifest themselves in the digital networked age?

The “social question” may not have been resolved, but for decades it felt as if it was neutralized. In the West after World War II, instrumental knowledge of how to manage the social was seen as necessary, and this reduced the intellectual range of the question to a somewhat closed circle of professional experts. Now, in the midst of a global economic downturn, can we see a renaissance of the social? Is all this talk about the rise of “social media” just a linguistic coincidence? Can we speak, in the never-ending aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, of a “return of the social”? Is there a growing class awareness, and if so, can it spread electronically? Despite widespread unemployment, growing income disparities, and the Occupy protests, it seems unlikely that we will see a global networked uprising. Protests are successful precisely because they are local, despite their network presence. How can the two separate entities of work and networked communication connect?

We can put such considerations into a larger, strategic context that the “social media question” poses. Do all these neatly administrated contacts and address books at some point spill over and leave the virtual realm, as the popularity of dating sites seems to suggest? Do we only share information, experiences, and emotions, or do we also conspire, as “social swarms,” to raid reality in order to create so-called real-world events? Will contacts mutate into comrades? It seems that social media solves the organizational problems that the suburban baby-boom generation faced fifty years ago: boredom, isolation, depression, and desire. How do we come together, right now? Do we unconsciously fear (or long for) the day when our vital infrastructure breaks down and we really need each other? Or should we read this Simulacrum of the Social as an organized agony over the loss of community after the fragmentation of family, marriage, and friendship? Why do we assemble these ever-growing collections of contacts? Is the Other, relabeled as “friend,” nothing more than a future customer or business partner? What new forms of social imaginary exist? At what point does the administration of others mutate into something different altogether? Will “friending” disappear overnight, like so many new media-related practices that vanished in the digital nirvana?

The container concept “social media,” describing a fuzzy collection of websites like Facebook, Digg, YouTube, Twitter, and Wikipedia, is not a nostalgic project aimed at reviving the once dangerous potential of “the social,” like an angry mob that demands the end of economic inequality. Instead, the social—to remain inside Baudrillard’s vocabulary—is reanimated as a simulacrum of its own ability to create meaningful and lasting social relations. Roaming around in virtual global networks, we believe that we are less and less committed to our roles in traditional community formations such as the family, church, and neighborhood. Historical subjects, once defined as citizens or members of a class possessing certain rights, have been transformed into subjects with agency, dynamic actors called “users,” customers who complain, and “prosumers.” The social is no longer a reference to society—an insight that troubles us theorists and critics who use empirical research to prove that people, despite all their outward behavior, remain firmly embedded in their traditional, local structures.

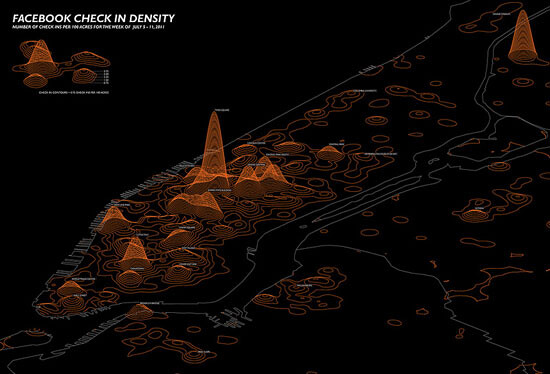

The social no longer manifests itself primarily as a class, movement, or mob. Neither does it institutionalize itself anymore, as happened during the postwar decades of the welfare state. And even the postmodern phase of disintegration and decay seems over. Nowadays, the social manifests itself as a network. Networked practices emerge outside the walls of twentieth-century institutions, leading to a “corrosion of conformity.” The network is the actual shape of the social. What counts—for instance, in politics and business—are the “social facts” as they present themselves through network analysis and its corresponding data visualizations. The institutional part of life is another matter, a realm that quickly falls behind, becoming a parallel universe. It is tempting to remain positive and portray a synthesis, further down the road, between the formalized power structures inside institutions and the growing influence of informal networks. But there is little evidence of this Third Way approach coming to pass. The PR-driven belief that social media will, one day, be integrated is nothing more than New Age optimism in a time of growing tensions over scarce resources. The social, which used to be the glue for repairing historical damage, can quickly turn into unstable, explosive material. A total ban is nearly impossible, even in authoritarian countries. Ignoring social media as background noise also backfires. This is why institutions, from hospitals to universities, hire swarms of temporary consultants to manage social media for them.

Social media fulfill the promise of communication as an exchange; instead of forbidding responses, they demand replies. Similar to an early writing of Baudrillard’s, social media can be understood as “reciprocal spaces of speech and response” that lure users to say something, anything.2 Later, Baudrillard changed his position and no longer believed in the emancipatory aspect of talking back to the media. Restoring the symbolic exchange wasn’t enough—and this feature is precisely what social media offer their users as an emancipatory gesture. For the late Baudrillard, what counted was the superior position of the silent majority.

In their 2012 pamphlet Declaration, Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri avoid discussing the larger social dimensions of community, cohesion, and society. What they witness is unconscious slavery: “People sometimes strive for their servitude as if it were their salvation.”3 It is primarily individual entitlement in social media that interests these theorists, not the social at large. “Is it possible that in their voluntary communication and expression, in their blogging and social media practices, people are contributing to instead of contesting repressive forces?” For us, the mediatized, work, and leisure can no longer be separated. But what about the equally obvious productive side of being connected to others?

Hardt and Negri make the mistake of reducing social networking to a media question, as if the internet and smartphones are only used to look up and produce information. Concerning the role of communication, they conclude that “nothing can beat the being together of bodies and the corporeal communication that is the basis of collective political intelligence and action.” Social links are probably nothing but fluff, a veritable world of sweet sassiness. In this way, the true nature of social life online remains out of sight, and thus unscrutinized. The meeting of the social and the media doesn’t have to be sold as some Hegelian synthesis, a world-historical evolution; however, the strong yet abstract concentration of social activity on today’s networked platforms is something that needs to be theorized. Hardt and Negri’s call to refuse mediation will have to move further. “We need to make new truths, which can be created by singularities in networks communicating and being there.” We need both networking and encampment. In their version of the social, “we swarm like insects” and act as “a decentralized multitude of singularities that communicates horizontally.”4 The actual power structures, and frictions, that emerge out of this constellation have yet to be addressed.

The search for the social online—it seems a brave but ultimately unproductive project to look for the remains of nineteenth-century European social theory. This is what makes the “precarious labor” debate about Marx and exploitation on Facebook so tricky.5 What we need to do instead is take the process of socialization at face value and refrain from well-meaning political intentions (such as the “Facebook revolutions” of the 2011 Arab Spring and the movement of the squares). The workings of social media are subtle, informal, and indirect. How can we understand the social turn in new media, beyond good and evil, as something that is both cold and intimate, as Israeli sociologist Eva Illouz described it in her book Cold Intimacies?6 Literature from the media industry and the IT industry tends to shy away from the question posed here. Virtues such as accessibility and usability do not explain what people are looking for “out there.” There are similar limits to the (professional) discourse of trust, which also tries to bridge the informal sphere and the legal sphere of rules and regulations.

The “obliteration of the social” has not led to a disappearance of sociology, but it has downgraded the importance of social theory in critical debates. A “web sociology” that has freed itself of the real-virtual dichotomies, not limiting its research scope to the “social implications of technology” (such as, for example, internet addiction), could play a critical role in developing a better understanding of how “class analysis” and mediatization are intertwined. As Eva Illouz wrote to me in response to this question: “If sociology has traditionally called on us to exert our shrewdness and vigilance in the art of making distinctions (between use value and exchange value; life world and colonization of the life world, etc.), the challenge that awaits us is to exercise the same vigilance in a social world which consistently defeats these distinctions.”7 Albert Benschop, the Amsterdam pioneer of web sociology and editor of SocioSite.net, proposes that we overcome the real-virtual distinction altogether. He makes an analogy to the Thomas theoreme, a classic theory in sociology, when he says, “If people define networks as real, they are real in their consequences.” For Benschop, the internet is not some “second-hand world.” The same could be said of the social. There is no second life, with different social rules and conventions. According to Benschop, this is why there is, strictly speaking, no additional discipline necessary.8 The discussion about the shape of the social relates to all of us; it should not be cooked up—and owned—solely by geeks and startup entrepreneurs. As Johan Sjerpstra puts it:

Welcome to the social abyss. We can no longer close our eyes for the real existing stupidity out there. We’re in it all together. Pierre Levy, please help us out: where is the collective intelligence now that we need it?

The social is not merely the (digital) awareness of the Other, even though the importance of “direct contact” should not be underestimated. There needs to be actual, real, existing interaction. This is the main difference between old broadcast media and the current social network paradigm. “Interpassivity,” the concept which points at a perceived growth of the delegation of passions and desires to others (the outsourcing of affect) as discussed, for instance, by Pfaller, Žižek, and van Oenen, is a nice but harmless concept in this (interactive) context.9 To question the current architectures and cultures of social media is not to be motivated by some kind of hidden, oppressed offline romanticist sentiment. Is there something like a justified feeling of overexposure, not just to information in general but to others as well? We all need a break from the social circus every now and then, but who can afford to cut off ties indefinitely? In the online context, the social requires our constant involvement, in the form of clicking. We need to make the actual link. Machines will not make the vital connection for us, no matter how much we delegate. It is no longer enough to build on your existing social capital. What social media do is algorithmically expand your reach—or at least they promise to.

Instead of merely experiencing our personal history as something that we reconcile with and feel the need to overcome (think of family ties, the village or suburb, school and college, church and colleagues from work), the social is seen as something that we are proud of, that we love to represent and show off. Social networking is experienced in terms of an actual potentiality: I could contact this or that person (but I won’t). From now on I will indicate my preferred brand (even without being asked). The social is the collective ability to imagine the connected subjects as a temporary unity. The power of connection is felt by many, and the simulations of the social on websites and in graphs are not so much secondary experiences or representations of something real; they are probes into a post-literate world ruled by images.

Martin Heidegger’s dictum “We don’t call, we are being called” runs empty here.10 On the internet, bots will contact you regardless, and the status updates of others, relevant or not, will pass before your eyes anyway. The filter failure is real. Once inside the busy flow of social media, the Call to Being comes from software and invites you to reply. This is where the cool and laid-back postmodern indifference of quasi-subversive attitudes comes to an end. It is meaningless not to bother—we are not friends anyway. Why stay on Facebook? Forget Twitter. These are cool statements, but they are now beside the point. The user is no longer in a “state of stupor.” The silence of the masses that Baudrillard spoke about has been broken. Social media has been a clever trick to get them talking. We have all been reactivated. The obscenity of common opinions and the everyday prostitution of private details is now firmly embedded in software and in billions of users.

The example Baudrillard used was the opinion poll, which he said undermines “the authentic existence of the social.” Baudrillard replaced the sad vision of the masses as an alienated entity with an ironic and object-centered vision. Now, thirty years deeper into the media era, even this vision has become internalized. In the Facebook age, surveys can be done continuously—without people’s direct participation in questionnaires and the like—through data mining. These algorithmic calculations run in the background and measure every single click, touch of the keyboard, and use of a keyword. For Baudrillard, this “positive absorption into the transparency of the computer” is even worse than alienation.11 The public has become a database full of users. The “evil genius of the social” has no other way to express itself than to go back to the streets and squares, guided and witnessed by the multitude of viewpoints that tweeting smartphones and recording digital cameras produce. In the same way that Baudrillard questioned the outcome of opinion polls as a subtle revenge of the common people on the political/media system, we should question the objective truth of the so-called Big Data originating from Google, Twitter, and Facebook. Most of the traffic on social media originates from millions of computers talking to each other. Active participation of ten percent of the user base is high. These users are assisted by an army of dutiful, hardworking software bots. The rest are inactive accounts. This is what object-oriented philosophy has yet come to terms with: a critique of the useless contingency.

The social media system no longer “plunges us into a state of stupor,” as Baudrillard said of media experience decades ago. Instead, it shows us the way to cooler apps and other products that elegantly make us forget yesterday’s flavor of the day. We simply click, tap, and drag the platform away, finding something else to distract us. This is how we treat online services: we leave them behind, if possible on abandoned hardware. Within weeks we have forgotten the icon, bookmark, or password. We do not have to revolt against the media of the Web 2.0 era, abandoning it in protest because of allegedly intrusive privacy policies; rather, we can confidently discard it, knowing it will eventually join the good old HTML ghost towns of the nineties.

Here is Baudrillard parsing the situation back in the old media days: “This is our destiny, subjected to opinion polls, information, publicity, statistics: constantly confronted with the anticipated statistical verification of our behavior, absorbed by this permanent refraction of our slightest movements, we are no longer confronted with our own will.” He discusses the move towards obscenity that is made in the permanent display of one’s own preferences (in our case, on social media platforms). There is a “redundancy of the social,” a “continual voyeurism of the group in relation to itself: it must at all times know what it wants … The social becomes obsessed with itself; through this auto-information, this permanent auto-intoxication.”12

The difference between the 1980s, when Baudrillard wrote these theses, and thirty years later can be found in the fact that all aspects of life have opened up to the logic of opinion polls. Not only do we have personal opinions about every possible event, idea, or product, but these informal judgments are also valuable to databases and search engines. People start to talk about products of their own accord; they no longer need incentives from outside. Twitter goes for the entire specter of life when it asks, “What’s happening?” Everything, even the tiniest info spark provided by the online public, is (potentially) relevant, ready to be earmarked as viral and trending, destined to be data-mined and, once stored, ready to be combined with other details. These devices of capture are totally indifferent to the content of what people say—who cares about your views? That’s network relativism: in the end it’s all just data, their data, ready to be mined, recombined, and flogged off. “Victor, are you still alive?”13 This is not about participation, remembrance, and forgetting. What we transmit are the bare signals indicating that we are still alive.

A deconstructivist reading of social media shouldn’t venture, once again, to reread the friendship discourse (“from Socrates to Facebook”) or to take apart the Online Self. No matter how hard it is to resist the temptation, theorists should shy away from their built-in “interpassive” impulse to call for a break (“book your offline holiday”). This position has played itself out. Instead, we need cybernetics 2.0—initiatives such as a follow-up to the original Macy conferences (1946 to 1953), but this time with the aim of investigating the cultural logic inside social media, inserting self-reflexivity in code, and asking what software architectures could be developed to radically alter the online social experience. We need input from the critical humanities and the social sciences; these disciplines need to start a dialogue with computer science. Are “software studies” initiatives up to such a task? Time will tell. Digital humanities, with its one-sided emphasis on data visualization, working with computer-illiterate humanities scholars as innocent victims, has so far made a bad start in this respect. We do not need more tools; what’s required are large research programs run by technologically informed theorists that finally put critical theory in the driver’s seat. The submissive attitude in the arts and humanities towards the hard sciences and industries needs to come to an end.

And how can philosophy contribute? The Western male self-disclosing subject no longer needs to be taken apart and contrasted with the liberated cyber-identity or “avatar” that roams around the virtual game worlds. Interesting players in the new media game can be found across the globe, from Africa to Brazil, India, and East Asia. For this, an IT-informed postcolonial theory has yet to be assembled. We should look today’s practices of the-social-as-electronic-empathy right in the eyes. How do you shape and administer your online affects? To put it in terms of theory: we need to extend Derrida’s questioning of the Western subject to the non-human agency of software (as described by Bruno Latour and followers of his Actor Network Theory). Only then we can get a better understanding of the cultural policy of aggregators, the role of search engines, and the editing wars on Wikipedia.

With its emphasis on Big Data, we can read the “renaissance of the social” in the light of sociology as the “positivist science of society.” As of yet there is no critical school in sight that could help us to properly read the social aura of the citizen as user. The term “social” has effectively been neutralized in its cynical reduction to data porn. Reborn as a cool concept in the media debate, the social manifests itself neither as dissent nor as subcultural. The social organizes the self as a techno-cultural entity, a special effect of software, which is rendered addictive by real-time feedback features. In the internet context, the social is neither a reference to the Social Question nor a hidden reminder of socialism as a political program. The social is precisely what it pretends to be: a calculated opportunity in times of distributed communication. In the end, the social turns out to be a graph, a more or less random collection of contacts on your screen that blabber on and on—until you intervene and put your own statement out there.

Thanks to Facebook’s simplicity, the online experience is a deeply human experience: the aim is to find the Other, not information. Ideally, the Other is online, right now. Communication works best if it is 24/7, global, mobile, fast, and short. Most appreciated is instantaneous exchange with “friended” users at chat-mode speed. This is social media at its best. We are invited to “burp out the thought you have right now—regardless of its quality, regardless of how it connects to your other thoughts.”14 The social presence of young people is the default here (according to the scholarly literature). We create a social sculpture, and then, as we do with most conceptual and participatory artworks, we abandon it, leaving it to be trashed by anonymous cleaners. This is similar to the faith inherent in all social media: it will be remembered as an individual experience of online community in the post-9/11 decade. And happily forgotten as the next distraction consumes our perpetual present.

It is said that social media has outgrown virtual communities (as described by Howard Rheingold in his 1993 book of the same name), but who really cares about the larger historical picture here? Many doubt whether Facebook and Twitter, in their current manifestations as platforms for the millions, still generate authentic online community experiences. What counts are the trending topics, the next platform, and the latest apps. Silicon Valley historians will one day explain the rise of “social networking sites” out of the ashes of the dot-com crisis, when a handful of survivors from the margins of the e-commerce boom-and-bust reconfigured viable concepts of the Web 1.0 era, stressing the empowerment of the user as content producer. The secret of Web 2.0, which kicked off in 2003, is the combination of (free) uploads of digital material with the ability to comment on other people’s efforts. Interactivity always consists of these two components: action and reaction. Chris Cree defines social media as “communication formats publishing user generated content that allow some level of user interaction,” a problematic definition that could include most of early computer culture.15 It is not enough to limit social media to uploading and self-promotion. It is the personal one-to-one feedback and small-scale viral distribution elements that are essential.

As Andrew Keen indicates in Digital Vertigo (2012), the social in social media is first and foremost an empty container; he adduces the exemplary hollow platitude that says the internet is “becoming the connective tissue of twenty-first century life.” According to Keen, the social is becoming a tidal wave that is flattening everything in its path. Keen warns that we will end up in an anti-social future, characterized by the “loneliness of the isolated man in the connected crowd.”16 Confined inside the software cages of Facebook, Google, and their clones, users are encouraged to reduce their social life to “sharing” information. The self-mediating citizen constantly broadcasts his or her state of being to an amorphous, numb group of “friends.” Keen is part of a growing number of (mainly) US critics warning us of the side effects of extensive social media use. From Sherry Turkle’s rant on loneliness, Nicholas Carr’s warnings on the loss of brain power and the ability to concentrate, to Evgeny Morozov’s critique of the utopian NGO world, to Jaron Lanier’s concern over the loss of creativity, what unites these commentators is their avoidance of what the social could alternatively be, were it not defined by Facebook and Twitter. The problem here is the disruptive nature of the social, which returns as a revolt against an unknown and unwanted agenda: vague, populist, radical-Islamist, driven by good-for-nothing memes.

The Other as opportunity, channel, or obstacle? You choose. Never has it been so easy to “auto-quantify” one’s personal surroundings. We follow our blog statistics and our Twitter mentions, check out friends of friends on Facebook, or go on eBay to purchase a few hundred “friends” who will then “like” our latest uploaded pictures and start a buzz about our latest outfit. Listen to how Dave Winer sees the future of news: “Start a river, aggregating the feeds of the bloggers you most admire, and the other news sources they read. Share your sources with your readers, understanding that almost no one is purely a source or purely a reader. Mix it all up. Create a soup of ideas and taste it frequently. Connect everyone that’s important to you, as fast as you can, as automatically as possible, and put the pedal to the metal and take your foot off the brake.”17 This is how programmers these days loosely glue everything together with code. Connect persons to data objects to persons. That’s the social today.

Chris Chesher, “How Computer Networks Became Social,” in Chris Chesher, Kate Crawford, and Anne Dunn, Internet Transformations: Language, Technology, Media and Power (forthcoming from Palgrave Macmillan in 2014).

Jean Baudrillard, “The Masses: Implosion of the Social in the Media,” New Literary History 16:3 (John Hopkins University Press, 1985), 1. See →.

All quotes here in and in the next paragraph are from Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Declaration (New York: Argo-Navis, 2012), 18–21.

Ibid., 35 (both quotes).

See the exchange “The $100bn Facebook question: Will capitalism survive ‘value abundance’?” on the nettime email list, early March 2012. Brian Holmes writes there in various postings: “What I have found very limiting in the discourse around so-called web 2.0 is the use of Marx’s notion of exploitation in the strict sense, where your labor power is alienated into the production of a commodity and you get an exchange value in return”… “For years I have been dismayed by a very common refusal to think. The dismaying part is that it’s based on the work of European history’s greatest political philosopher, Karl Marx. It consists in the assertion that social media exploits you, that play is labor, and that Facebook is the new Ford Motor Co.” … “The ‘apparatus of capture,’ introduced by Deleuze and Guattari and developed into a veritable political economy by the Italian Autonomists and the Multitudes group in Paris, does something very much like that, though without using the concept of exploitation” … “Social media do not exploit you the way a boss does. It emphatically _does_ sell statistics about the ways you and your friends and correspondents make use of your human faculties and desires, to nasty corporations that do attempt to capture your attention, condition your behavior and separate you from your money. In that sense, it does try to control you and you do create value for it. Yet that is not all that happens. Because you too do something with it, something of your own. The dismaying thing in the theories of playbour, etc, is that they refuse to recognize that all of us, in addition to being exploited and controlled, are overflowing sources of potentially autonomous productive energy. The refusal to think about this—a refusal which mostly circulates on the left, unfortunately—leaves that autonomous potential unexplored and partially unrealized.”

Eva Illouz, Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007).

Private email correspondence, March 5, 2012.

Albert Benschop, “Virtual Communities.” See →.

See Robert Pfaller, Ästhetik der Interpassivität (Hamburg: Plilo Fine Arts, 2008) (in German) and Gijs van Oenen, Nu even niet! Over de interpassieve samenleving (Amsterdam: van Gennep, 2011) (in Dutch).

See Avital Ronell, The Telephone Book (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1989).

Jean Baudrillard, “The Masses: Implosion of the Social in the Media,” New Literary History, 16:3 (John Hopkins University Press, 1985), 5.

Ibid., 580.

Standard phrase uttered by Professor Professor, a Bavarian character who speaks English with a heavy German accent in the BBC animated series “The Secret Show” from 2007.

See →.

Read more at →.

Andrew Keen, Digital Vertigo (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2012), 13.

See →.