An Architektur: The term “commons” occurs in a variety of historical contexts. First of all, the term came up in relation to land enclosures during pre- or early capitalism in England; second, in relation to the Italian autonomia movement of the 1960s; and third, today, in the context of file-sharing networks, but also increasingly in the alter-globalization movement. Could you tell us more about your interest in the commons?

Massimo De Angelis: My interest in the commons is grounded in a desire for the conditions necessary to promote social justice, sustainability, and happy lives for all. As simple as that. These are topics addressed by a large variety of social movements across the world that neither states nor markets have been able to tackle, and for good reasons. State policies in support of capitalist growth are policies that create just the opposite conditions of those we seek, since they promote the working of capitalist markets. The latter in turn reproduce socio-economic injustices and hierarchical divisions of power, environmental catastrophes and stressed-out and alienated lives. Especially against the background of the many crises that we are facing today—starting from the recent global economic crisis, and moving to the energy and food crises, and the associated environmental crisis—thinking and practicing the commons becomes particularly urgent.

Massimo De Angelis: Commons are a means of establishing a new political discourse that builds on and helps to articulate the many existing, often minor struggles, and recognizes their power to overcome capitalist society. One of the most important challenges we face today is, how do we move from movement to society? How do we dissolve the distinctions between inside and outside the movement and promote a social movement that addresses the real challenges that people face in reproducing their own lives? How do we recognize the real divisions of power within the “multitude” and produce new commons that seek to overcome them at different scales of social action? How can we reproduce our lives in new ways and at the same time set a limit to capital accumulation?

The discourse around the commons, for me, has the potential to do those things. The problem, however, is that capital, too, is promoting the commons in its own way, as coupled to the question of capitalist growth. Nowadays the mainstream paradigm that has governed the planet for the last thirty years—neoliberalism—is at an impasse, which may well be terminal. There are signs that a new governance of capitalism is taking shape, one in which the “commons” are important. Take for example the discourse of the environmental “global commons,” or that of the oxymoron called “sustainable development,” which is an oxymoron precisely because “development” understood as capitalist growth is just the opposite of what is required by “sustainability.” Here we clearly see the “smartest section of capital” at work, which regards the commons as the basis for new capitalist growth. Yet you cannot have capitalist growth without enclosures. We are at risk of getting pushed to become players in the drama of the years to come: capital will need the commons and capital will need enclosures, and the commoners at these two ends of capital will be reshuffled in new planetary hierarchies and divisions.

Massimo De Angelis: Let me address the question of the definition of the commons. There is a vast literature that regards the commons as a resource that people do not need to pay for. What we share is what we have in common. The difficulty with this resource-based definition of the commons is that it is too limited, it does not go far enough. We need to open it up and bring in social relations in the definition of the commons.

Commons are not simply resources we share—conceptualizing the commons involves three things at the same time. First, all commons involve some sort of common pool of resources, understood as non-commodified means of fulfilling peoples needs. Second, the commons are necessarily created and sustained by communities—this of course is a very problematic term and topic, but nonetheless we have to think about it. Communities are sets of commoners who share these resources and who define for themselves the rules according to which they are accessed and used. Communities, however, do not necessarily have to be bound to a locality, they could also operate through translocal spaces. They also need not be understood as “homogeneous” in their cultural and material features. In addition to these two elements—the pool of resources and the set of communities—the third and most important element in terms of conceptualizing the commons is the verb “to common”—the social process that creates and reproduces the commons. This verb was recently brought up by the historian Peter Linebaugh, who wrote a fantastic book on the thirteenth-century Magna Carta, in which he points to the process of commoning, explaining how the English commoners took the matter of their lives into their own hands. They were able to maintain and develop certain customs in common—collecting wood in the forest, or setting up villages on the king’s land—which, in turn, forced the king to recognize these as rights. The important thing here is to stress that these rights were not “granted” by the sovereign, but that already-existing common customs were rather acknowledged as de facto rights.

An Architektur: We would like to pick up on your remark on the commons as a new political discourse and practice. How would you relate this new political discourse to already existing social or political theory, namely Marxism? To us it seems as if at least your interpretation of the commons is based a lot on Marxist thinking. Where would you see the correspondences, where lie the differences?

Massimo De Angelis: The discourse on the commons relates to Marxist thinking in different ways. In the first place, there is the question of interpreting Marx’s theory of primitive accumulation. In one of the final chapters of volume one of Capital, Marx discusses the process of expropriation and dispossession of commoners, which he refers to as “primitive accumulation,” understood as the process that creates the precondition of capitalist development by separating people from their means of production. In sixteenth- to eighteenth-century England, this process became known as “enclosure”—the enclosure of common land by the landed nobility in order to use the land for wool production. The commons in these times, however, formed an essential basis for the livelihood of communities. They were fundamental elements for people’s reproduction, and this was the case not only in Britain, but all around the world. People had access to the forest to collect wood, which was crucial for cooking, for heating, for a variety of things. They also had access to common grassland to graze their own livestock. The process of enclosure meant fencing off those areas to prevent people from having access to these common resources. This contributed to mass poverty among the commoners, to mass migration and mass criminalization, especially of the migrants. These processes are pretty much the same today all over the world. Back then, this process created on the one hand the modern proletariat, with a high dependence on the wage for its reproduction, and the accumulation of capital necessary to fuel the industrial revolution on the other.

Marx has shown how, historically, primitive accumulation was a precondition of capitalist development. One of the key problems of the subsequent Marxist interpretations of primitive accumulation, however, is the meaning of “precondition.” The dominant understanding within the Marxist literature—apart from a few exceptions like Rosa Luxemburg—has always involved considering primitive accumulation as a precondition fixed in time: dispossession happens before capitalist accumulation takes place. After that, capitalist accumulation can proceed, exploiting people perhaps, but with no need to enclose commons since these enclosures have already been established. From the 1980s onwards, the profound limitations of this interpretation became obvious. Neoliberalism was rampaging around the world as an instrument of global capital. Structural adjustment policies, imposed by the IMF (International Monetary Fund), were promoting enclosures of “commons” everywhere: from community land and water resources to entitlements, to welfare benefits and education; from urban spaces subject to new pro-market urban design and developments to rural livelihoods threatened by the “externalities” of environmentally damaging industries, to development projects providing energy infrastructures to the export processing zones. These are the processes referred to by the group Midnight Notes Collective as “new enclosures.”

Image found on Wikicommons (searchword: IMF) “Monetary Fund Headquarters, Washington, DC.”

The identification of “new enclosures” in contemporary capitalist dynamics urged us to reconsider traditional Marxist discourse on this point. What the Marxist literature failed to understand is that primitive accumulation is a continuous process of capitalist development that is also necessary for the preservation of advanced forms of capitalism for two reasons. Firstly, because capital seeks boundless expansion, and therefore always needs new spheres and dimensions of life to turn into commodities. Secondly, because social conflict is at the heart of capitalist processes—this means that people do reconstitute commons anew, and they do it all the time. These commons help to re-weave the social fabric threatened by previous phases of deep commodification and at the same time provide potential new ground for the next phase of enclosures.

Thus, the orthodox Marxist approach—in which enclosure and primitive accumulation are something that only happens during the formation of a capitalist system in order to set up the initial basis for subsequent capitalist development—is misleading. It happens all the time; today as well people’s common resources are enclosed for capitalist utilization. For example, rivers are enclosed and taken from local commoners who rely on these resources, in order to build dams for fueling development projects for industrialization. In India there is the case of the Narmada Valley; in Central America there is the attempt to build a series of dams called the Puebla-Panama Plan. The privatization of public goods in the US and in Europe has to be seen in this way, too. To me, however, it is important to emphasize not only that enclosures happen all the time, but also that there is constant commoning. People again and again try to create and access the resources in a way that is different from the modalities of the market, which is the standard way for capital to access resources. Take for example the peer-to-peer production happening in cyberspace, or the activities in social centers, or simply the institutions people in struggle give themselves to sustain their struggle. One of the main shortcomings of orthodox Marxist literature is de-valuing or not seeing the struggles of the commoners. They used to be labeled as backwards, as something that belongs to an era long overcome. But to me, the greatest challenge we have in front of us is to articulate the struggles for commons in the wide range of planetary contexts, at different layers of the planetary wage hierarchy, as a way to overcome the hierarchy itself.

An Architektur: The notion of the commons as a pre-modern system that does not fit in a modern industrialized society is not only used by Marxists, but on the neoliberal side, too. It is central to neoliberal thinking that self-interest is dominant vis-à-vis common interests and that therefore the free market system is the best possible way to organize society. How can we make a claim for the commons against this very popular argument?

Massimo De Angelis: One of the early major pro-market critiques of the commons was the famous article “The Tragedy of the Commons” by Gerrit Hardin, from 1968. Hardin argued that common resources will inevitably lead to a sustainability tragedy because the individuals accessing them would always try to maximize their personal revenue and thereby destroy them. For example, a group of herders would try to get their own sheep to eat as much as possible. If every one did that then of course the resource would be depleted. The policy implications of this approach are clear: the best way to sustain the resource is either through privatization or direct state management. Historical and economic research, however, has shown that existing commons of that type rarely encountered these problems, because the commoners devise rules for accessing resources. Most of the time, developing methods of ensuring the sustainability of common resources has been an important part of the process of commoning.

There is yet a third way beyond markets or states, and this is community self-management and self-government. This is another reason why it is important to keep in mind that commons, the social dimension of the shared, are constituted by the three elements mentioned before: pooled resources, community, and commoning. Hardin could develop a “tragedy of the commons” argument because in his assumption there existed neither community nor commoning as a social praxis, there were only resources subject to open access.

Furthermore, it is important to note that the problem of the commons cannot be simply described as a question of self-interest versus common interests. Often, the key problem is how individual interests can be articulated in such a way as to constitute common interests. This is the question of commoning and of community formation, a big issue that leads to many open questions. Within Marxism, there is generally a standard way to consider the question of common interests: these are given by the “objective” conditions in which the “working class” finds itself vis-à-vis capital as the class of the exploited. A big limitation of this standard interpretation is that “objectivity” is always an inter-subjective agreement. The working class itself is fragmented into a hierarchy of powers, often in conflicts of interest with one another, conflicts materially reproduced by the workings of the market. This means that common interests cannot be postulated, they can only be constructed.

Comic strip of Marx’s Capital explaining “What is Society?”

An Architektur: This idea of the common interest that has to be constructed in the first place—what consequences does it have for conceptualizing possible subjects of change? Would this have to be everybody, a renewed form of an avant-garde or a regrouped working class?

Massimo De Angelis: It is of course not possible to name the subject of change. The usefulness of the usual generalizations—“working class,” “proletariat,” “multitude,” etc.—may vary depending on the situation, but generally has little analytical power apart from indicating crucial questions of “frontline.” This is precisely because common interests cannot be postulated but can only be constituted through processes of commoning, and this commoning, if of any value, must overcome current material divisions within the “working class,” “proletariat,” or “multitude.” From the perspective of the commons, the wage worker is not the emancipatory subject because capitalist relations also pass through the unwaged labor, is often feminized, invisible, and so on. It is not possible to rely on any “vanguard,” for two reasons. Firstly, because capitalist measures are pervasive within the stratified global field of production, which implies that it hits everybody. Secondly, because the most “advanced” sections of the global “working class”—whether in terms of the level of their wage or in terms of the type of their labor (it does not matter if these are called immaterial workers or symbolic analysts)—can materially reproduce themselves only on the basis of their interdependence with the “less advanced” sections of the global working class. It has always been this way in the history of capitalism and I have strong reasons to suspect it will always be like this as long as capitalism is a dominant system.

To put it in another way: the computer and the fiber optic cables necessary for cyber-commoning and peer-to-peer production together with my colleagues in India are predicated on huge water usage for the mass production of computers, on cheap wages paid in some export-processing zones, on the cheap labor of my Indian high-tech colleagues that I can purchase for my own reproduction, obtained through the devaluation of labor through ongoing enclosures. The subjects along this chain can all be “working class” in terms of their relation to capital, but their objective position and form of mutual dependency is structured in such a way that their interests are often mutually exclusive.

An Architektur: Stavros, what is your approach towards the commons? Would you agree with Massimo’s threefold definition and the demands for action he derives from that?

Stavros Stavrides: First, I would like to bring to the discussion a comparison between the concept of the commons based on the idea of a community and the concept of the public. The community refers to an entity, mainly to a homogeneous group of people, whereas the idea of the public puts an emphasis on the relation between different communities. The public realm can be considered as the actual or virtual space where strangers and different people or groups with diverging forms of life can meet.

The notion of the public urges our thinking about the commons to become more complex. The possibility of encounter in the realm of the public has an effect on how we conceptualize commoning and sharing. We have to acknowledge the difficulties of sharing as well as the contests and negotiations that are necessarily connected with the prospect of sharing. This is why I favor the idea of providing ground to build a public realm and give opportunities for discussing and negotiating what is good for all, rather than the idea of strengthening communities in their struggle to define their own commons. Relating commons to groups of “similar” people bears the danger of eventually creating closed communities. People may thus define themselves as commoners by excluding others from their milieu, from their own privileged commons. Conceptualizing commons on the basis of the public, however, does not focus on similarities or commonalities but on the very differences between people that can possibly meet on a purposefully instituted common ground.

We have to establish a ground of negotiation rather than a ground of affirmation of what is shared. We don’t simply have to raise the moral issues about what it means to share, but to discover procedures through which we can find out what and how to share. Who is this we? Who defines this sharing and decides how to share? What about those who don’t want to share with us or with whom we do not want to share? How can these relations with those “others” be regulated? For me, this aspect of negotiation and contest is crucial, and the ambiguous project of emancipation has to do with regulating relationships between differences rather than affirming commonalities based on similarities.

An Architektur: How does this move away from commons based on similarities, towards the notion of difference, influence your thinking about contemporary social movements or urban struggles?

Stavros Stavrides: For me, the task of emancipatory struggles or movements is not only what has to be done, but also how it will be done and who will do it. Or, in a more abstract way: how to relate the means to the ends. We have suffered a lot from the idea that the real changes only appear after the final fight, for which we have to prepare ourselves by building some kind of army-like structure that would be able to effectively accomplish a change in the power relations. Focused on these “duties” we tend to postpone any test of our values until after this final fight, as only then we will supposedly have the time to create this new world as a society of equals. But unfortunately, as we know and as we have seen far too often, this idea has turned out to be a nightmare. Societies and communities built through procedures directed by hierarchical organizations, unfortunately, exactly mirrored these organizations. The structure of the militant avant-garde tends to be reproduced as a structure of social relations in the new community.

Thus, an essential question within emancipatory projects is: can we as a group, as a community or as a collectivity reflect our ideas and values in the form that we choose to carry out our struggle? We have to be very suspicious about the idea of the avant-garde, of those elected (or self-selected) few, who know what has to be done and whom the others should follow. To me, this is of crucial importance. We can no longer follow the old concept of the avant-garde if we really want to achieve something different from today’s society.

Here are very important links to the discussion about the commons, especially in terms of problematizing the collectivity of the struggle. Do we intend to make a society of sharing by sharing, or do we intend to create this society after a certain period in which we do not share? Of course, there are specific power relations between us, but does this mean that some have to lead and others have to obey the instructors? Commons could be a way to understand not only what is at stake but also how to get there. I believe that we need to create forms of collective struggle that match collective emancipatory aims, forms that can also show us what is worthy of dreaming about an emancipated future.

An Architektur: Massimo, you put much emphasis on the fact that commoning happens all the time, also under capitalist conditions. Can you give a current example? Where would you see this place of resistance? For Marx it was clearly the factory, based on the analysis of the exploitation of labor, which gave him a clear direction for a struggle.

Massimo De Angelis: The factory for Marx was a twofold space: it was the space of capitalist exploitation and discipline—this could of course also be the office, the school, or the university—but it was also the space in which social cooperation of labor occurred without the immediate mediation of money. Within the factory we have a non-commoditized space, which would fit our definition of the commons as the space of the “shared” at a very general level.

An Architektur: Why non-commoditized?

Massimo De Angelis: Because when I work in a capitalist enterprise, I may get a wage in exchange for my labor power, but in the moment of production I do not participate in any monetary transactions. If I need a tool, I ask you to pass me one. If I need a piece of information, I do not have to pay a copyright. In the factory—that we are using here as a metaphor for the place of capitalist production—we may produce commodities, but not by means of commodities, since goods stopped being commodities in the very moment they became inputs in the production process. I refer here to the classical Marxian distinction between labor power and labor. In the factory, labor power is sold as a commodity, and after the production process, products are sold. In the very moment of production, however, it is only labor that counts, and labor as a social process is a form of “commoning.” Of course, this happens within particular social relations of exploitation, so maybe we should not use the same word, commoning, so as not to confuse it with the commoning made by people “taking things into their own hands.” So, we perhaps should call it “distorted commoning,” where the measure of distortion is directly proportional to the degree of the subordination of commoning to social measures coming from outside the commoning, the one given by management, by the requirement of the market, etc. In spite of its distortions, I think, it is important to consider what goes on inside the factory as also a form of commoning. This is an important distinction that refers to the question of how capital uses the commons. I am making this point because the key issue is not really how we conceive of commoning within the spheres of commons, but how we reclaim the commons of our production that are distorted through the imposition of capital’s measure of things.

Image found on Wikicommons (searchword: commoners) “Wigpool Common.This was open land, grazed through commoner’s rights.”

This capitalist measure of things is also imposed across places of commoning. The market is a system that articulates social production at a tremendous scale, and we have to find ways to replace this mode of articulation. Today, most of what is produced in the common—whether in a distorted capitalist commons or alternative commons—has to be turned into money so that commoners can access other resources. This implies that commons can be pitted against one another in processes of market competition. Thus we might state as a guiding principle that whatever is produced in the common must stay in the common in order to expand, empower, and sustain the commons independently from capitalist circuits.

Stavros Stavrides: This topic of the non-commodified space within capitalist production is linked to the idea of immaterial labor, theorized, among others, by Negri and Hardt. Although I am not very much convinced by the whole theory of “empire” and “the multitude,” the idea that within the capitalist system the conditions of labor tend to produce commons, even though capitalism, as a system acts against commons and for enclosures, is very attractive to me. Negri and Hardt argue that with the emergence of immaterial labor—which is based on communicating and exchanging knowledge, not on commodified assets in the general sense, but rather on a practice of sharing—we have a strange new situation: the change in the capitalist production from material to immaterial labor provides the opportunity to think about commons that are produced in the system but can be extracted and potentially turned against the system. We can take the notion of immaterial labor as an example of a possible future beyond capitalism, where the conditions of labor produce opportunities for understanding what it means to work in common but also to produce commons.

Of course there are always attempts to control and enclose this sharing of knowledge, for example the enclosure acts aimed at controlling the internet, this huge machine of sharing knowledge and information. I do not want to overly praise the internet, but this spread of information to a certain degree always contains the seed of a different commoning against capitalism. There is always both, the enclosures, but also the opening of new possibilities of resistance. This idea is closely connected to those expressed in the anti-capitalist movement claiming that there is always the possibility of finding within the system the very means through which you can challenge it. Resistance is not about an absolute externality or the utopia of a good society. It is about becoming aware of opportunities occurring within the capitalist system and trying to turn them against it.

Massimo De Angelis: We must, however, also make the point that seizing the internal opportunities that capitalism creates can also become the object of co-optation. Take as an example the capitalist use of the commons in relation to seasonal workers. Here commons can be used to undermine wages or, depending on the specific circumstances, they can also constitute the basis for stronger resistance and greater working-class power. The first case could be seen, for example, in South African enclaves during the Apartheid regime, where lower-level wages could be paid because seasonal workers were returning to their homes and part of the reproduction was done within these enclaves, outside the circuits of capital. The second case is when migrant seasonal workers can sustain a strike precisely because, due to their access to common resources, their livelihoods are not completely dependent on the wage, something which happened, for example, in Northern Italy a few decades ago. Thus, the relation between capitalism and the commons is always a question of power relations in a specific historic context.

An Architektur: How would you evaluate the importance of the commons today? Would you say that the current financial and economic crisis and the concomitant delegitimation of the neoliberal model brought forward, at least to a certain extent, the discussion and practice of the commons? And what are the respective reactions of the authorities and of capitalism?

Massimo De Angelis: In every moment of crisis we see an emergence of commons to address questions of livelihood in one way or the other. During the crisis of the 1980s in Britain there was the emergence of squatting, alternative markets, or so called Local Exchange Trading Systems, things that also came up in the crisis in Argentina in 2001.

Regarding the form in which capitalism reacts and reproduces itself in relation to the emergence of commoning, three main processes can be observed. First, the criminalization of alternatives in every process of enclosure, both historically and today. Second, a temptation of the subjects fragmented by the market to return to the market. And third, a specific mode of governance that ensures the subordination of individuals, groups and their values, needs and aspirations under the market process.

An Architektur: But then, how can we relate the commons and commoning to state power? Are the commons a means to overcome or fight the state or do you think they need the state to guarantee a societal structure? Would, at least in theory, the state finally be dissolved through commoning? Made useless, would it thus disappear? Stavros, could you elaborate on this?

Stavros Stavrides: Sometimes we tend to ignore the fact that what happens in the struggle for commons is always related to specific situations in specific states, with their respective antagonisms. One always has to put oneself in relation to other groups in the society. And of course social antagonisms take many forms including those produced by or channeled through different social institutions. The state is not simply an engine that is out there and regulates various aspects of production or various aspects of the distribution of power. The state, I believe, is part of every social relation. It is not only a regulating mechanism but also produces a structure of institutions that mold social life. To be able to resist these dominant forms of social life we have to eventually struggle against these forces which make the state a very dominant reality in our societies.

In today’s world, we often interpret the process of globalization as the withering away of states, so that states are no longer important. But actually the state is the guarantor of the necessary conditions for the reproduction of the system. It is a guarantor of violence, for example, which is not a small thing. Violence, not only co-optation, is a very important means of reproducing capitalism, because by no means do we live in societies of once-and-for-all legitimated capitalist values. Instead, these values must be continuously imposed, often by force. The state is also a guarantor of property and land rights, which are no small things either, because property rights establish forms of control on various aspects of our life. Claims of property rights concern specific places that belong to certain people or establishments, which might also be international corporations. The state, therefore, is not beyond globalization; it is in fact the most specific arrangement of powers against which we can struggle.

Stavros Stavrides: I am thus very suspicious or reserved about the idea that we can build our own small enclaves of otherness, our small liberated strongholds that could protect us from the power of the state. I don’t mean that it is not important to build communities of resistance, but rather than framing them as isolated enclaves, we should attempt to see them as a potential network of resistance, collectively representing only a part of the struggle. If you tend to believe that a single community with its commons and its enclosed parameter could be a stronghold of liberated otherness, then you are bound to be defeated. You cannot avoid the destruction that comes from the power of the state and its mechanisms. Therefore, we need to produce collaborations between different communities as well as understand ourselves as belonging to not just one of these communities. We should rather understand ourselves as members of different communities in the process of emerging.

An Architektur: But how can it be organized? What could this finally look like?

Stavros Stavrides: The short answer is a federation of communities. The long answer is that it has to do with the conditions of the struggle. I think that we are not for the replacement of the capitalist state by another kind of state. We come from long traditions, both communist and anarchist, of striving for the destruction of the state. I think we should find ways in today’s struggles to reduce the presence of the state, to oblige the state to withdraw, to force the state to be less violent in its responses. To seek liberation from the jurisdiction of the state in all its forms, that are connected with economical, political, and social powers. But, for sure, the state will be there until something—not simply a collection of struggles, but something of a qualitatively different form—happens that produces a new social situation. Until then we cannot ignore the existence of the state because it is always forming its reactions in terms of what we choose to do.

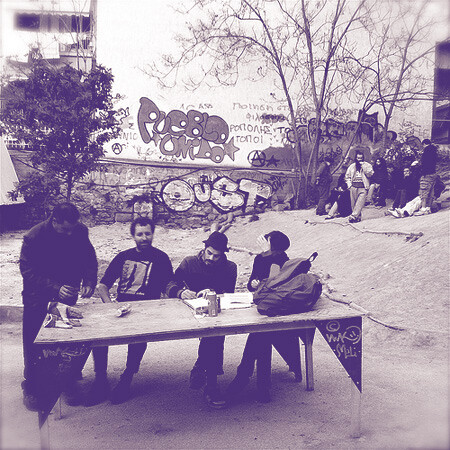

Massimo De Angelis: Yes, I agree that is crucial. The state is present in all these different processes, but it is also true that we have to find ways to disarticulate these powers. One example is the occupied park in Exarcheia, a parking lot that was turned into a park through an ongoing process of commoning. The presence of the state is very obvious, just fifty meters around the corner there is an entire bus full of riot police and rows of guards. One of the problems in relation to the park is the way in which the actions of the police could be legitimized by making use of complaints about the park by its neighbors. And there are of course reasons to complain. Some of the park’s organizers told me that apparently every night some youth hang out there, drinking and trashing the place, making noise and so on. The organizers approached them, asking them not to do that. And they replied “Oh, are you the police?” They were also invited to participate in the assembly during the week, but they showed no interest. According to some people I have interviewed, they were showing an individualistic attitude, one which we have internalized by living in this capitalist society; the idea that this is my space where I can do whatever I want—without, if you like, a process of commoning that would engage with all the issues of the community. But you have to somehow deal with this problem, you cannot simply exclude those youngsters, not only as a matter of principle, but also because it would be completely deleterious to do so. If you just exclude them from the park, you have failed to make the park an inclusive space. If you do not exclude them and they continue with their practices, it would further alienate the local community and provide an opening for the police and a legitimization of their actions. So in a situation like this you can see some practical answers to those crucial questions we have discussed—there are no golden rules.

Stavros Stavrides: I would interpret the situation slightly differently. Those people you refer to were not saying that they have a right as individual consumers to trash the park. They were saying that the park is a place for their community, a place for alternative living or for building alternative political realms. They certainly refer to some kind of commoning, but only to a very specific community of commoners. And this is the crucial point: they did not consider the neighbors, or at least the neighbors’ habitude, as part of their community. Certain people conceive of this area as a kind of liberated stronghold in which they don’t have to think about those others outside. Because, in the end, who are those others outside? They are those who “go to work everyday and do not resist the system.”

To me, these are cases through which we are tested, through which our own ideas about what it means to share or what it means to live in public are tested. We can discuss the park as a case of an emergent alternative public space. And this public space can be constituted only when it remains contestable in terms of its use. Public spaces which do not simply impose the values of a sovereign power are those spaces produced and inhabited through negotiating exchanges between different groups of people. As long as contesting the specific character and uses of alternative public spaces does not destroy the collective freedom to negotiate between equals, contesting should be welcome. You have to be able to produce places where different kinds of lives can coexist in terms of mutual respect. Therefore any such space cannot simply belong to a certain community that defines the rules; there has to be an ongoing, open process of rulemaking.

Massimo De Angelis: There are two issues here. First of all, I think this case shows that whenever we try to produce commons, what we also need is the production of the respective community and its forms of commoning. The Navarinou Park is a new commons and the community cannot simply consist of the organizers. The organizers I have talked to act pretty much as a sort of commons entrepreneurs, a group of people who are trying to facilitate the meeting of different communities in the park, to promote encounters possibly leading to more sustained forms of commoning. Thus, when we are talking about emergent commons like these ones, we are talking about spaces of negotiation across diverse communities, the bottom line of what Stavros referred to as “public space.” Yet, we also cannot talk about the park as being a “public space” in the usual sense, as a free-for-all space, one for which the individual does not have to take responsibility, like a park managed by the local authority.

The second point is that another fundamental aspect of commoning can be exemplified by the park—the role of reproduction. We have learned from feminists throughout the last few decades that for every visible work of production there is an invisible work of reproduction. The people who want to keep the park will have to work hard for its reproduction. This does not only mean cleaning the space continuously, but also reproducing the legitimacy to claim this space vis-à-vis the community, vis-à-vis the police and so on. Thinking about the work of reproduction is actually one of the most fundamental aspects of commoning. How will the diverse communities around this park come together to share the work of reproduction? That is a crucial test for any commons.

An Architektur: But how can we imagine this constant process of negotiation other than on a rather small local level?

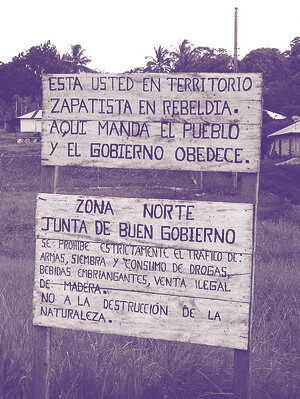

Stavros Stavrides: To me this is not primarily a question of scale, it is more a fundamental question of how to approach these issues. But if you want to talk about a larger-scale initiative, I would like to refer to the Zapatista movement. For the Zapatistas, the process of negotiation takes two forms: inter-community negotiation, which involves people participating in assemblies, and negotiations with the state, which involves the election of representatives. The second form was abruptly abandoned as the state chose to ignore any agreement reached. But the inter-community negotiation process has evolved into a truly alternative form of collective self-government. Zapatistas have established autonomous regions inside the area of the Mexican state in order to provide people with the opportunity to actually participate in self-governing those regions. To not simply participate in a kind of representative democracy but to actually get involved themselves. Autonomous communities established a rotation system that might look pretty strange to us, with a regular change every fifteen or thirty days. So, if you become some kind of local authority of a small municipality, then, just when you start to know what the problems are and how to tangle with them, you have to leave the position to another person. Is this logical? Does this system bring about results that are similar to other forms of governing, or does it simply produce chaos? The Zapatistas insist that it is more important that all the people come into these positions and get trained in a form of administration that expresses the idea of “governing by obeying the community” (mandar obedeciendo). The rotation system effectively prevents any form of accumulation of individual power. This system might not be the most effective in terms of administration but it is effective in terms of building and sustaining this idea of a community of negotiation and mutual respect.

Zapatista “rebel” territory. Photo: Hajor, 2005

Yes, establishing rules and imposing them is more effective, but it is more important to collectively participate in the process of creating and checking the rules, if you intend to create a different society. We have to go beyond the idea of a democracy of “here is my view, there is yours—who wins?” We need to find ways of giving room to negotiate the differences. Perhaps I tend to overemphasize the means, the actual process, and not the effective part of it, its results. There are of course a lot of problems in the Zapatista administration system but all these municipalities are more like instances of a new world trying to emerge and not prototypes of what the world should become.

We can also take as an example the Oaxaca rebellion, which worked very well. Those people have actually produced a city-commune, which to me is even more important than the glorious commune of Paris. We had a very interesting presentation by someone from Oaxaca here in Athens, explaining how during those days they realized that “they could do without them”—them meaning the state, the power, the authorities. They could run the city collectively through communal means. They had schools, and they had captured the radio and TV station from the beginning. They ran the city facing all the complexities that characterize a society. Oaxaca is a rather small city of around 600,000 inhabitants and of course it is not Paris. But we had the chance to see these kind of experiments, new forms of self-management that can produce new forms of social life—and as we know, the Oaxaca rebellion was brutally suppressed. But, generally speaking, until we see these new forms of society emerging we don’t know what they could be like. And I believe we have to accept that!

An Architektur: Stavros, you mentioned that the administration and rotation system of the Zapatistas should not be taken as a prototype of what should come. Does this mean that you reject any kind of idea of or reflection about models for a future society?

Stavros Stavrides: I think it is not a question of a model. We cannot say that some kind of model exists, nor should we strive for it. But, yes, we need some kind of guiding principles. For me, however, it is important to emphasize that the commons cannot be treated only as an abstract idea, they are inextricably intertwined with existing power relations. The problem is, how can we develop principles through which we can judge which communities actually fight for commons? Or, the other way round, can struggles for commons also be against emancipatory struggles? How do we evaluate this? I think in certain historical periods, not simply contingencies, you can have principles by which you can judge. For example, middle-class neighborhoods that tend to preserve their enclave character will produce communities fighting for commons but against the idea of emancipation. Their notion of commons is based on a community of similar people, a community of exclusion and privilege.

Principles are however not only discursive gestures, they have to be seen in relation to the person or the collective subject who refers to these principles in certain discourses and actions. Therefore, reference to principles could be understood as a form of performative gesture. If I am saying that I am for or against those principles what does this mean for my practice? Principles are not only important in judging discursive contests but can also affect the way a kind of discourse is connected to practice. For example, if the prime minister of Greece says in a pre-election speech that he wants to eradicate all privileges we of course know he means only certain privileges for certain people. So, what is important is not only the stating of principles, but also the conditions under which this statement acquires its meaning. That is why I am talking about principles presuming that we belong to the same side. I am of course also assuming that we enter this discussion bearing some marks of certain struggles, otherwise it would be a merely academic discussion.

An Architektur: Let’s imagine that we were left alone, what would we do? Do we still need the state as an overall structure or opponent? Would we form a state ourselves, build communities based on commons or turn to egoistic ways of life? Maybe this exercise can bring us a little further …

Massimo De Angelis: I dare to say that “if we are left alone” we may end up doing pretty much the same things as we are now: keep the race going until we re-program ourselves to sustain different types of relations. In other words, you can assume that “we are left alone” and still work in auto-pilot because nobody knows what else to do. There is a lot of learning that needs to be done. There are a lot of prejudices we have built by becoming—at least to a large extent—homo economicus, with our cost-benefit calculus in terms of money. There is a lot of junk that needs to be shed, other things that need to be valorized, and others still that we need to just realize.

Yet auto-pilots cannot last forever. In order to grow, the capitalist system must enclose, but enclosures imply strategic agency on the part of capital. Lacking this under the assumption that “we are left alone,” the system would come to a standstill and millions of people would ask themselves: What now? How do we reproduce our livelihoods? The question that needs to be urgently problematized in our present context would come out naturally in the (pretty much absurd) proposition you are making. There is no easy answer that people could give. Among other things, it would depend a lot on power relations within existing hierarchies, because even if “we are left alone” people would still be divided into hierarchies of power. But one thing that is certain to me is that urban people, especially in the North, would have to begin to grow more food, reduce their pace of life, some begin to move back to the countryside, and look into each other’s eyes more often. This is because “being left alone” would imply the end of the type of interdependence that is constituted with current states’ policies. What new forms of interdependence would emerge? Who knows. But the real question is: what new forms of interdependence can emerge given the fact that we will never be left alone?

Image found on Wikicommons (searchword: money) “English ‘Money-tree’ near Bolton Abbey, North Yorkshire, Papa November (cc)”

Concerning the other part of your question, yes, we could envisage a “state,” but not necessarily in the tragic forms we have known. The rational kernel of “the state” is the realm of context—the setting for the daily operations of commoners. From the perspective of nested systems of commons at larger and larger scales, the state can be conceptualized as the bottom-up means through which the commoners establish, monitor, and enforce their basic collective and inter-commons rules. But of course the meaning of establishing, monitoring, and—especially—enforcing may well be different from what is meant today by it.

Stavros Stavrides: Let’s suppose that we have been left alone, which I don’t think will ever be the case. But anyway. Does that mean that we are in a situation where we can simply establish our own principles, our own forms of commons, that we are in a situation where we are equal? Of course not!

A good example is the case of the occupied factories in Argentina. There, the workers were left alone in a sense, without the management, the accountants, and engineers, and without professional knowledge of how to deal with various aspects of the production. They had to develop skills they did not have before. One woman, for example, said that her main problem in learning the necessary software programs to become an accountant for the occupied factory, was that she first had to learn how to read and write. So, imagine the distance that she had to bridge! And eventually, without wanting it, she became one of the newly educated workers that could lead the production and develop strategies for the factory. Although she would not impose them on the others, who continued to work in the assembly line and did not develop skills in the way she did, she became a kind of privileged person. Thus, no matter how egalitarian the assembly was, you finally develop the same problems you had before. You have a separation of people, which is a result of material circumstances. Therefore, you have to develop the means to fight this situation. In addition to producing the commons, you have to give the power to the people to have their own share in the production process of these commons—not only in terms of the economic circumstances but in terms of the socialization of knowledge, too. You have to ensure that everybody is able to speak and think, to become informed, and to participate. All of these problems have erupted in an occupied factory in Argentina, not in a future society.

Anthropological research has proved that there have been and still exist societies of commoning and sharing and that these societies—whether they were food gatherers or hunters—do not only conceive of property in terms of community-owned goods, but that they have also developed a specific form of eliminating the accumulation of power. They have actively produced forms of regulating power relations through which they prevent someone from becoming a leader. They had to acknowledge the fact that people do not possess equal strength or abilities, and at the same time they had to develop the very means by which they would collectively prevent those differences from becoming separating barriers between people, barriers that would eventually create asymmetries of power. Here you see the idea of commons not only as a question of property relations but also as a question of power distribution.

So, coming back to your question, when we are left alone we have to deal with the fact that we are not equal in every aspect. In order to establish this equality, we have to make gestures—not only rules—but gestures which are not based on a zero-sum calculus. Sometimes somebody must offer more, not because anyone obliges him or her but because he or she chooses to do so. For example, I respect that you cannot speak like me, therefore I step back and I ask you to speak in this big assembly. I do this knowing that I possess this kind of privileged ability to talk because of my training or talents. This is not exactly a common, this is where the common ends and the gift begins—to share you have to be able to give gifts. To develop a society of equality does not mean leveling but sustaining the ability of everybody to participate in a community, and that is not something that happens without effort. Equality is a process not a state. Some may have to “yield” in order to allow others—those more severely underprivileged—to be able to express their own needs and dreams.

Massimo De Angelis: I think that the gift and the commons may not be two modalities outside one another. “Gift” may be a property of the commons, especially if we regard these not as fixed entities but as processes of commoning. Defining the “what,” “how,” and “who” of the commons also may include acts of gifts and generosity. In turn, these may well be given with no expectation of return. However, as we know, the gift, the act of generosity, is often part of an exchange, too, where you expect something in return.

Massimo De Angelis: The occupied factory we just talked about exemplifies an arena in which we have the opportunity to produce commons, not only through making gift gestures but also by turning the creative iteration of these gestures into new institutions. And these arenas for commoning potentially exist everywhere. Yet every arena finds itself with particular boundaries—both internal and external ones. In the case of the occupied factory, the internal boundaries are given by the occupying community of workers, who have to consider their relation to the outside, the unemployed, the surrounding communities, and so on. The choices made here will also affect the type of relations to and articulation with other arenas of commoning.

Another boundary that comes up in all potential arenas of commoning, setting a limit to the endeavors of the commoners, is posited outside them, and is given by the pervasive character of capitalist measure and values. For example, the decision of workers to keep the production going implies to a certain extent accepting the measuring processes given by a capitalist market which puts certain constraints on workers such as the need for staying competitive, at least to some degree. All of a sudden they had to start to self-organize their own exploitation, and this is one of the major problems we face in these kind of initiatives, an issue that can only be tackled when a far higher number of commoning arenas arise and ingenuity is applied in their articulation.

But before we reach that limit posed by the outside, there is still a lot of scope for constitution, development, and articulation of subjectivities within arenas of commoning. This points to the question of where our own responsibility and opportunity lie. If the limit posed from the outside on an arena of commoning is the “no” that capital posits to the commons “yes,” to what extent can our constituent movement be a positive force that says no to capital’s no?

An Architektur: But then, when will a qualitative difference in society be achieved such that we are able to resist those mechanisms of criminalization, temptation, and governance Massimo spoke about before? What would happen if half of the factories were self-governed?

Stavros Stavrides: I don’t know when a qualitative difference will be achieved. 50% is a very wild guess! Obviously that would make a great difference. But I think a very small percentage makes a difference as well. Not in terms of producing enclaves of otherness surrounded by a capitalist market, but as cases of collective experimentation through which you can also convince people that another world is possible. And those people in the Argentinean factories have actually managed to produce such kind of experiments, not because they have ideologically agreed on the form of society they fight for, but because they were authentically producing their own forms of everyday resistance, out of the need to protect their jobs after a major crisis. Many times they had to rediscover the ground on which to build their collectively sustained autonomy. The power of this experiment, however, lies on its possibility to spread—if it keeps on enclosing itself in the well-defined perimeter of an “alternative enclave,” it is bound to fail.

I believe that if we see and experience such experiments, we can still hope for another world and have glimpses of this world today. It is important to test fragments of this future in our struggles, which is also part of how to judge them—and I think these collective experiences are quite different from the alternative movements of the 1970s. Do we still strive for developing different life environments that can be described as our own “Christianias”? To me, the difference lies in the porosity, in the fact that the areas of experiment spill over into society. If they are only imagined as liberated strongholds they are bound to lose. Again, there is something similar we could learn from the Zapatista movement that attempted to create a kind of hybrid society in the sense that it is both pre-industrial and post-industrial, both pre-capitalist and post-capitalist at the same time. To me, this, if you want, unclear situation, which of course is only unclear due to our frozen and limited perception of society, is very important.

An Architektur: How would you describe Athens’ uprising last December in this relation? At least in Germany much focus was put on the outbreak of violence. What do you think about what has happened? Have things changed since then?

Stavros Stavrides: One of the things that I have observed is that at first both the leftists and the anarchists didn’t know what to do. They were not prepared for this kind of uprising which did not happen at the very bottom of the society. There were young kids from every type of school involved. Of course there were immigrants taking part but this was not an immigrant revolt. Of course there were many people suffering from deprivation and injustice who took part but this was not a “banlieue type” uprising either. This was a peculiar, somehow unprecedented, kind of uprising. No center, just a collective networking without a specific point from which activities radiated. Ideas simply criss-crossed all over Greece and you had initiatives you couldn’t imagine a few months ago, a lot of activities with no name or with improvised collective signatures. For example, in Syros, an island with a long tradition of working-class struggles, the local pupils surrounded the central police station and demanded that the police officers come outside, take off their hats and apologize for what happened. And they did it. They came out in full formation. This is something that is normally unimaginable.

This polycentric eruption of collective action, offering glimpses of a social movement, which uses means that correspond to emancipating “ends,” is, at least to my mind, what is new and what inspired so many people all over the world. I tend to be a bit optimistic about that. Let me not overestimate what is new, there were also some very unpleasantly familiar things happening. You could see a few “Bonapartist” groups behaving as if they were conducting the whole situation. But this was a lie, they simply believed that.

The Navarinou Park in Exarcheia, Athens

What is also important is that the spirit of collective, multifarious actions did not only prevail during the December days. Following the December uprising, something qualitatively new happened in various initiatives. Take the initiative of the Navarinou Park in Exarcheia. This would not have been possible without the experience of December. Of course, several anarchist and leftist projects around Exarcheia already existed and already produced alternative culture and politics, but never before did we have this kind of initiative involving such a variety of people in such different ways. And, I think, after December various urban movements gained a new momentum, understanding that we weren’t simply demanding something but that we had a right to it. Rejecting being governed and taking our lives into our own hands, no matter how ambiguous that may be, is a defining characteristic of a large array of “after December” urban movement actions.

An Architektur: We have discussed a large variety of different events, initiatives, and projects. Can we attempt to further relate our findings to their spatial and urban impacts, maybe by more generally trying to envision a city entirely based on the commons?

Stavros Stavrides: To think about a city based on commons we have to question and conceptualize the connection of space and the commons. It would be interesting to think of the production of space as an area of commons and then discuss how this production has to be differentiated from today’s capitalist production of space. First of all, it is important to conceive space and the city as not primarily quantities—which is the dominant perception—the quantified space of profit-making, where space always has a value and can easily be divided and sold. So, starting to think about space as related to the commons means to conceptualize it as a form of relations rather than as an entity, as a condition of comparisons instead of an established arrangement of positions. We have to conceive space not as a sum of defined places, which we should control or liberate but rather as a potential network of passages linking one open place to another. Space, thus, becomes important as a constitutive dimension of social action. Space indeed “happens” as different social actions literally produce different spatial qualities. With the prospect of claiming space as a form of commons, we have to oppose the idea that each community exists as a spatially defined entity, in favor of the idea of a network of communicating and negotiating social spaces that are not defined in terms of a fixed identity. Those spaces thus retain a “passage” character.

Once more, we have to reject the exclusionary gesture which understands space as belonging to a certain community. To think of space in the form of the commons means not to focus on its quantity, but to see it as a form of social relationality providing the ground for social encounters. I tend to see this kind of experiencing-with and creation of space as the prospect of the “city of thresholds.” Walter Benjamin, seeking to redeem the liberating potential of the modern city, developed the idea of the threshold as a revealing spatiotemporal experience. For him, the flaneur is a connoisseur of thresholds: someone who knows how to discover the city as the locus of unexpected new comparisons and encounters. And this awareness can start to unveil the prevailing urban phantasmagoria which has reduced modernity to a misfired collective dream of a liberated future. To me, the idea of an emancipating spatiality could look like a city of thresholds. A potentially liberating city can be conceived not as an agglomerate of liberated spaces but as a network of passages, as a network of spaces belonging to nobody and everybody at the same time, which are not defined by a fixed-power geometry but are open to a constant process of (re)definition.

There is a line of thinking that leads to Lefebvre and his notion of the “right to the city” as the right that includes and combines all rights. This right is not a matter of access to city spaces (although we should not underestimate specific struggles for free access to parks, etc.), it is not simply a matter of being able to have your own house and the assets that are needed to support your own life, it is something which includes all those demands but also goes beyond them by creating a higher level of the commons. For Lefebvre the right to the city is the right to create the city as a collective work of art. The city, thus, can be produced through encounters that make room for new meanings, new values, new dreams, new collective experiences. And this is indeed a way to transcend pure utility, a way to see commons beyond the utilitarian horizon.