Categories

Subjects

Authors

Artists

Venues

Locations

Calendar

Filter

Done

September 18, 2024 – Review

Whitney Biennial Performance Program

Sanna Almajedi

Taja Cheek—currently artistic director at Performance Space New York, and an artist in her own right as L’Rain—has long advocated for the inclusion of sound artists and musicians in the gallery space, as central figures rather than an entertainment vehicle to lure crowds. This year’s Whitney Biennial featured a five-part performance program, curated by Cheek, featuring an array of performances deeply rooted in sound. Artists Debit, Sarah Hennies, Holland Andrews, Alex Tatarsky, and JJJJJerome Ellis presented electronic music, improvised sounds, an experimental music ensemble, and a sonic exploration of language.

The program began with Debit, playing music from her album The Long Count (2022), which imagines the music of the Mayan civilization through a theatrical and fantastical three-act performance, using intense drone sounds and samples of precious and eerie wind instrumentation. The stage consisted of a mountain made out of a pile of dirt/wood, spot lights and a curtain that was lifted at the end of the show to unveil the Whitney’s majestic view of the Hudson River, alluding perhaps to a call for the land. Debit used synthesizers which, according to the press release, “have sampled and processed the sounds of Late Postclassic Maya wind instruments. Using tones from …

March 30, 2024 – Review

81st Whitney Biennial, “Even Better Than the Real Thing”

Ben Eastham

Walking through this survey of American art in the age of anger and anxiety, I kept returning to the curatorial statement’s seemingly innocuous proposal that new technologies are “complicating our understanding of what is real.” Are our horizons now so narrow, it occurred to me, that an algorithm’s ability to generate a derivative image is really more consciousness-expanding than such longstanding preoccupations of art as spiritual experience or the natural world? Or might the title’s appeal to something “better” serve to distract us from the already complicated and unarguably real events playing out beyond the walls of the museum, with which this biennial can seem reluctant to engage?

A generation of artists are, on the show’s evidence, retreating from a hostile public sphere into their own carefully cultivated worlds. This tendency manifests both in the valorization of marginalized identities through the adaptation of folk traditions to the present—notably ektor garcia’s use of crochet to articulate a nomadic cross-border experience—and in the tendency towards opacity, most explicitly in the panels of smoked black glass suspended precariously over the audience’s heads by Charisse Pearlina Weston (of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust, 2022). Many of the realities …

April 21, 2023 – Review

“Refigured”

Travis Diehl

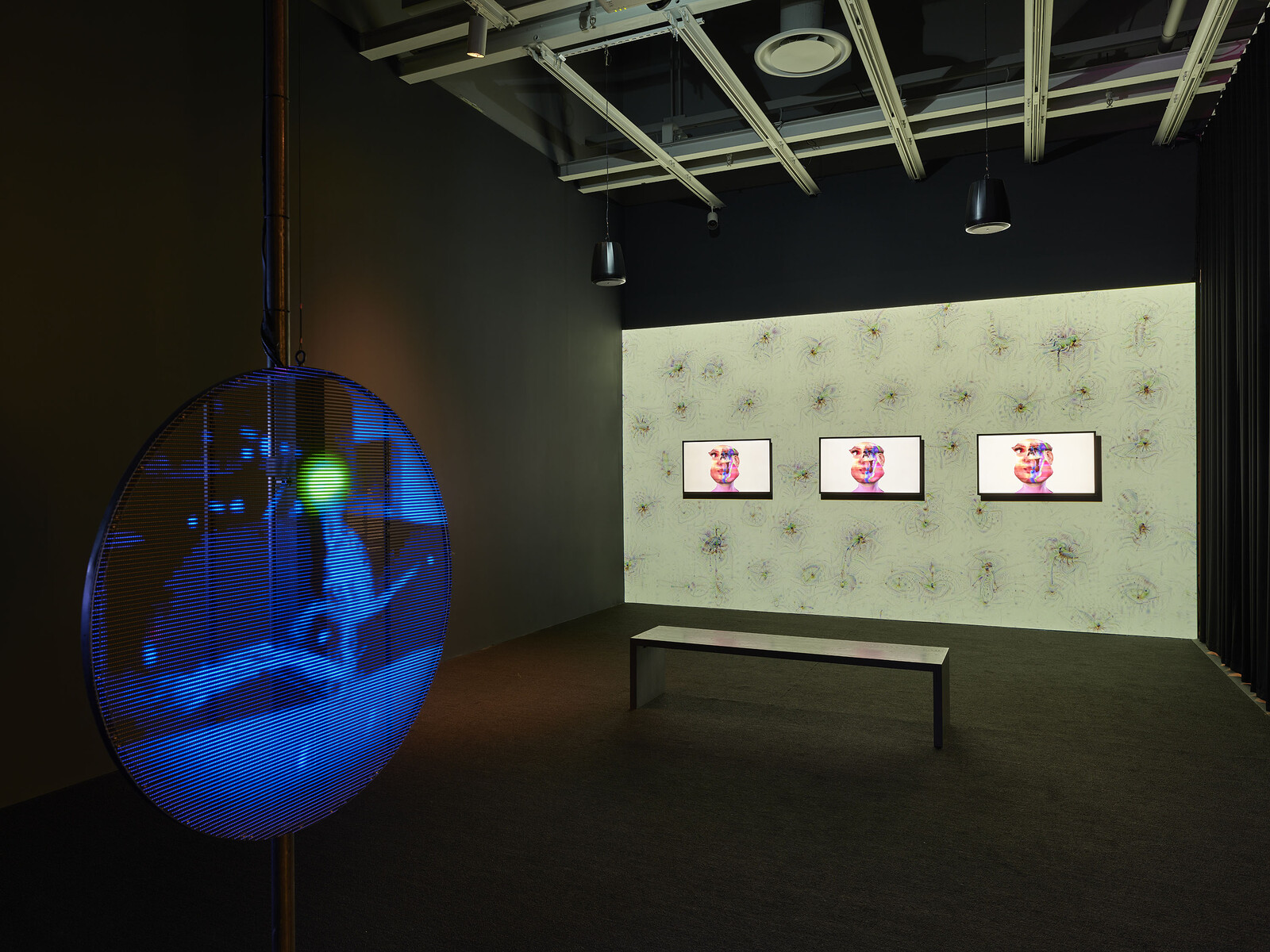

Among a spring flush of screen-, code-, and tech-related museum shows, “Refigured” at the Whitney stands out for its concision. The exhibition’s frame may seem vague—the human figure vis-a-vis technology at times verges on a universalized body—but the five works by six artists pulled by in-house curator Christiane Paul from the Whitney’s holdings maintain a fairly tight focus on the physical possibilities of digital bodies, from statues to demigods to talking heads. In Auriea Harvey’s Ox (2020) and Ox v1-dv2 (apotheosis) (2021), for instance, a muscular, berobed humanoid called Ox—which the wall label describes as an avatar for the artist—appears three times over: a pigmented statuette around 20 cm tall, a 3D model presented on a monitor, and an AR version pinned nearby and visible through an iPad tethered to its plinth. The artist’s intentions notwithstanding, Ox exists in digital and psychic “space” as a concept, a potentiality, and these various renderings are all concessions to display in a physical room.

In fact, as each new struggling trillion-dollar metaverse venture demonstrates, even state-of-the-art interfaces between the digital and physical “realms” remain pretty clunky (and the hardware here is not state of the art). The redundancy of Ox means there are …

April 5, 2022 – Review

80th Whitney Biennial, “Quiet as It’s Kept”

Dina Ramadan

In her 1988 lecture, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature,” Toni Morrison explained that the opening sentence of her 1970 novel The Bluest Eye—“Quiet as it’s kept”—was a familiar idiom from her childhood, usually whispered by Black women exchanging gossip, signaling a confidence shared. “The conspiracy is both held and withheld, exposed and sustained,” Morrison tells us. By borrowing this expression for the 80th edition of the Whitney Biennial, curators David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards promise the intimacy of knowledge bestowed, an exploration of the tantalizing space between hidden and revealed, a quiet reflection on whispered truths.

Unfortunately, the possibilities of this title are not fully explored; the curators instead pursue a series of “hunches” which are much less satisfying. The two main floors of the biennial are constructed in opposition to each other, the upper story a dark maze, restricted and confined, while the lower level is an airy relief, open and invigorating. This contrast is intended to reflect what the curatorial statement describes as “the acute polarity of our society,” although it is never clear how the works on each floor speak specifically to these fissures.

A recurring concern through the exhibition is a palpable disillusionment …

December 4, 2020 – Review

Salman Toor’s “How Will I Know”

Murtaza Vali

Nine months since the pandemic first hit New York, it is hard not to be moved by Salman Toor’s tender and luminous paintings, fifteen of which make up “How Will I Know,” his first solo show in a museum. In them young queer men gather inside and outside bars, dance joyously in apartments, embrace tenderly, and chat quietly on stoops and sofas, banal scenes of everyday intimacy and sociality that our seemingly interminable forced isolation has rendered both unfamiliar and precious. Skillfully composed of accumulations of short sketchy brush strokes, they picture the innocent ease of pre-pandemic revelry when the simple act of coming together was still untainted by the invisible threat of contagion.

Though inspired by moments from his life, Toor’s scenes are composed entirely from memory and imagination, and form visual analogues to the literary genre of autofiction, as co-curator Ambika Trasi persuasively argues in an accompanying essay published online. Some are given a dazzling emerald tint, energizing their quotidian settings with the buzz of dreamy fabulation. Toor conceives of his slender young male figures as marionettes, a quality emphasized through their slightly elongated noses á la Pinocchio. However, their sleepy downcast eyes, drooped shoulders, and limp, …

May 24, 2019 – Review

79th Whitney Biennial

Travis Diehl

Remember when America was hard to see? Boy, is it obvious now. The Whitney Biennial 2019, curated by Jane Panetta and Rujeko Hockley, has a marked interest in the alter-local, doing some overdue national soul-searching, as well as catching up to artists who have been doing this kind of reparative work all along. There is Joe Minter from Birmingham, Alabama, whose assemblages of rusty tools and metal imagine an “African village” in America, a stunning euphemism that is lost on no one. The agglomerations of plant matter and mass commodities by Puerto Rican artist Daniel Lind-Ramos (such as Maria-Maria [2019], in which an emergency FEMA tarp clothes a Virgin-like figure) are at once elusively bitter, ritualistic, and ruthlessly compromised, like a straw on a Caribbean beach. Curran Hatleberg’s lucid photographs document America’s rural poor over the past decade: folks on their stoops between weedy squares of lawn (Untitled [Front Porch], 2016), children in what seems like the aftermath of a natural disaster (Untitled [Girl with Snake], 2016), a half-dozen men in an auto junkyard waiting (for what?) around a fresh, grave-sized pit (Untitled [Hole], 2016). A half-hour video by Steffani Jemison, Sensus Plenior (2017), portrays a gospel mime in Harlem …

March 26, 2019 – Feature

New York City Roundup

Amy Zion

Twenty-five years ago, a group of young dealers, including Pat Hearn, Colin de Land, and Matthew, Marks started the first contemporary art fair in New York at the Gramercy Park Hotel. Titled the Gramercy International Art Fair, it spanned floors 12, 14, and 15 (there is no 13, of course) of the hotel, with each gallery taking over a room or suite. In the first iteration in 1994, Tracey Emin slept in the bed in the room where her work was displayed (by Jay Jopling/White Cube). In 1997, Holly Solomon installed two TV screens as part of a work by Nam June Paik in her room’s bathtub. After outgrowing the hotel, in 1999, the fair moved to the original site of the infamous 1913 Armory Show and changed its name. Now it fills two West Side piers and includes a modern/twentieth-century art portion alongside the contemporary. There are more fairs that share the week with the Armory—the Independent, which celebrated its 10th anniversary, Volta (more on that later), and Spring Break, among others.

Amid talks and other initiatives marking the quarter-century celebrations, at the fair there was a room several booths wide that included documentation and restaging of works from the …

March 21, 2017 – Feature

78th Whitney Biennial

Chris Sharp

The stakes surrounding this Whitney Biennial are, to say the least, high. Indeed, it’s hard to imagine a biennial being under more pressure to signify, to mean, to produce meaning, to attempt to offer some special and tangible insight into our current moment. Instead, what the curators Christopher Lew and Mia Locks offer is art. This is not to say, of course, that the art presented here is divorced from our current harrowing reality, by any means, but that it does not forfeit its unique transformative power in the face of it. Lew’s and Locks’s love of and faith in art is refreshingly unequivocal. Nor is this to say that the biennial they have curated is devoid of the political, insofar as one of the capacities of the political is to seek to imagine alternatives to the status quo. In the alternative imagined here, an ideal diversity and gender balance reigns. Of the agreeably modest and negotiable number of 63 artists and artist collectives, this biennial possesses more artists of color than any other in its past. That diversity is not limited to ethnicity, gender, and geography (artists hail from as far afield here as Puerto Rico and Seattle, although …

March 7, 2014 – Review

77th Whitney Biennial

Kevin McGarry

The most streamlined mythology of the past two decades of the Whitney Biennial goes something like this: 1993 represented the Big Bang of art and identity politics, and since then, the curve has bobbed up and down like a sine wave, going above and below the axis of overthought mediocrity towards an ever more platitudinous parody of itself. It is, after all, the biennial that everyone… loves to hate. Shoot me now. Framing it this way can be as mind numbing as discussing the weather, and yet, it is nearly as inescapable.

Perhaps drawing from its upper Manhattan terroir, the Whitney Biennial is an inimitable, enduringly anachronistic, and extremely self-referential institution. Each edition rehashes the questions “What is contemporary?” and “What is American?”—often to post-rational ends. Convoluted curatorial conceit is the most dangerous pitfall threatening state-of-the-art-world survey shows today. The best biennial I’ve seen in the past couple of years was Luiz Pérez-Oramas, André Severo, and Tobi Maier’s 2012 30th São Paulo Biennial about, simply, “poetics”—a theme so loose and extensible that the exhibition wore it as a heartening halo rather than a pretentious noose. In this respect, the 2014 Whitney Biennial does not fail. Well, actually, it does, but only …

March 23, 2012 – Review

76th Whitney Biennial

Stephen Squibb

Partial, relaxed, and idiosyncratic are not typically positive associations for large survey shows. But these have been multiplying recently, and perhaps that is why that most venerable of panoramas, the Whitney Biennial, finds itself relieved, a little, of its historical pretensions towards completeness. Any survey is just one of an infinite number that could have been, after all, but it’s rare that curators are secure enough to start with that knowledge rather than resort to it as an excuse after the fact. The 2012 Biennial is so blessed—Thomas Beard, Ed Halter, Jay Sanders, and Elisabeth Sussman are to blame—and the result is a wonderfully open, strange presentation. Other editions have contained a larger selection of more successful works, but I’ve never before left a biennial so keen to return, or found myself wishing that the Whitney weren’t quite so far away.

The chief reason is that so much of the work is spread out over the run of the show, appearing only at specific times. Thus, as you have perhaps heard, almost the entire fourth floor is given over to a large performance space to be inhabited by various artists in various ways. And if the show has a signature, …

March 9, 2012 – Review

"Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials"

Cindy Nemser / Anna Gritz

Cindy Nemser’s “The Art of Frustration” warrants a second take because of her critical view onto a time period that is now fetishized almost blindly. At hand of what is most likely the exhibition “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials” at the Whitney Museum in 1969, the review reveals a writer coming to terms with the birth of conceptual and process art. Linking both conceptual and process art’s inherent critique of the art “establishment” to the student revolts of the time, Nemser identifies a lack of influence as the root of the frustration. Nemser claims that this privation leads to a self-referential system of art as entertainment that vies for attention via shock while no longer carrying any greater relevancy. Significantly, she doesn’t mention a single artist by name nor does she focus in depth on any of the work. Whether or not one agrees with her sweeping criticism, this type of writing, detached from formal concerns, favors a socio-political analysis that links artistic strategies to measures beyond the art world. Pitching art against technology, Nemser says, “The greatest example of art today is to be found in the IBM building,” a statement which after 40 years still leaves a sting.

—Anna Gritz …

August 4, 2010 – Review

"Jill Magid: A Reasonable Man in a Box," the Whitney Museum, New York

Paddy Johnson

When Jill Magid wrote “What is a reasonable man in a box?” on the Whitney’s wall I suspect she already knew the answer. The text references the a leaked 2004 memorandum from the US Justice Department prescribing legal means for the CIA to employ illegal torture techniques such as confinement with insects. Slightly more complex than typically seen on an episode of Law and Order, the government’s jargon reduces “legal” torture to: “remove the possibility of permanent physical harm and you can do what you want”, the core of which Magid questions. After all, if you’re imprisoned in a box, how could anyone assume that it would not damage your physical and mental health?

Departing from her usual performative based works, Magid re-imagines the first floor gallery as a dark confinement box and projects a sentimental sepia-toned video of a scorpion’s shadow on the back wall. Every once and a while a pair of long tweezers descend to toy with the bug, catching and releasing it repeatedly. This is its own torturous game, and the shadow suggests only an imagined presence. At the opposite end of the gallery a vinyl-type reproduction of the memo—albeit marred by redaction—is affixed to the wall.

Magid …

Load more