Meta is a collaboration with TextWork, editorial platform of the Fondation Pernod Ricard, which reflects on the relationship between artists and writers. Following on from her essay on the work of Benoît Maire for Textwork, the curator Caterina Riva considers how the artist’s attitude towards waste and recycling resonates with her own writing process.

Finding the right tone and structure to tackle Benoît Maire’s oeuvre was tough. My hunch was to adopt a journalistic approach—more New Yorker culture desk than contemporary art analysis—something that could bypass art criticism’s claims to objectivity, but also avoid a personal subjectivity that might risk alienating the reader. After having assembled information from and around the artist, i.e. the evidence, I had to establish my vantage point and the voice in which to make intelligible the cloud of philosophical, digital, and painterly information that surrounds and feeds Maire’s artmaking. When I studied Curating, one professor would insist on the foreground, background and middle ground as strategies to imagine the layout of an exhibition; it struck me that these three concepts could lend themselves to writing, and to this author, writing in her second language, trying to negotiate her materials and ideas within an ongoing shift of perspectives.

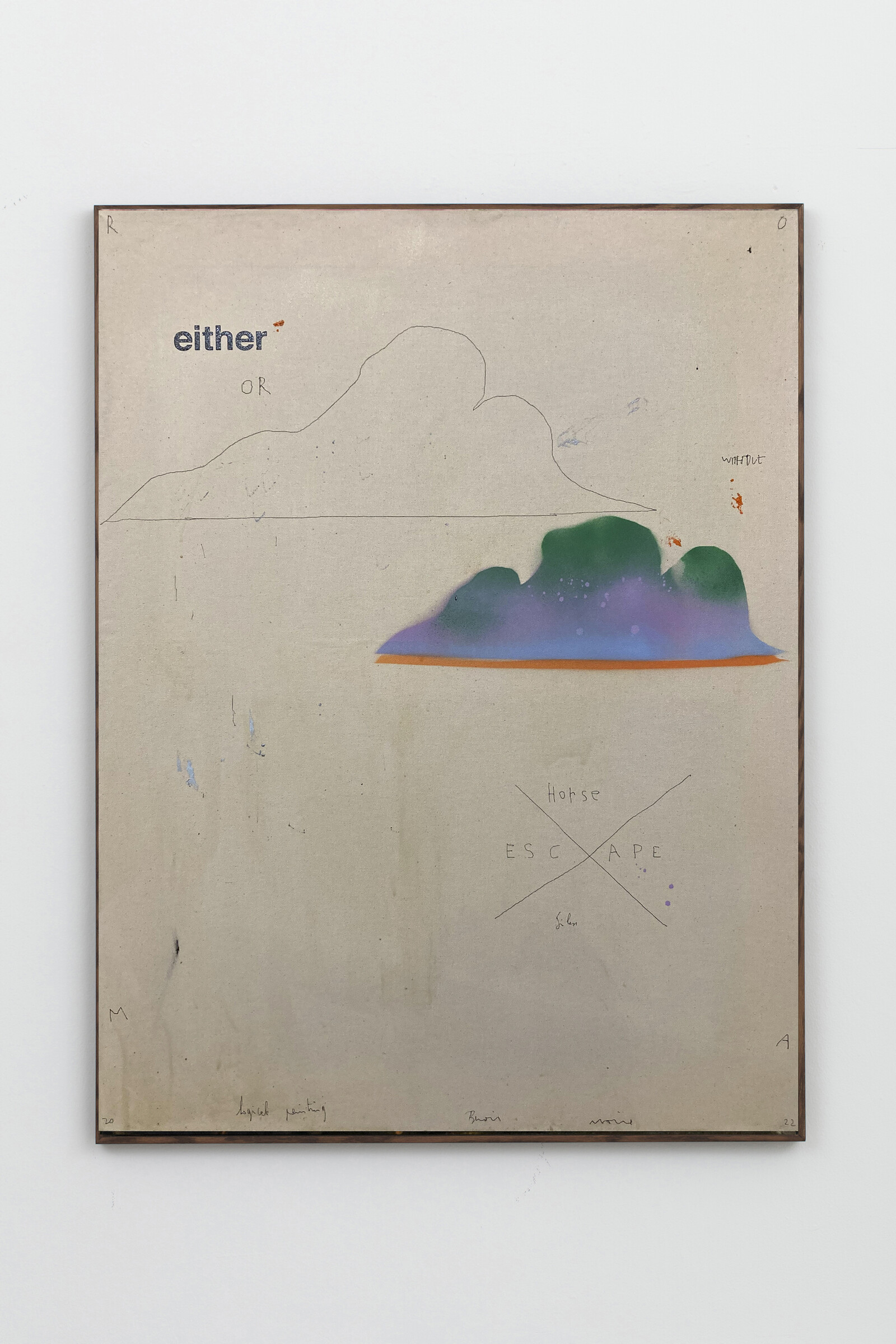

The process of editing my first draft—including the incorporation of some helpful clarifications from the French translator—required patience: re-reading the text over and over, reworking paragraphs, and deleting phrases. According to Maire’s methodology, waste is not what is rejected in the making of art, but what remains and morphs in the path towards an idea, a sculpture, an exhibition, a paragraph. Some elements might recede into the background of the wall, the painting, or the page, and others move forward in a continuous rearrangement of parts. The grid, a viewing tool used by Maire in his “Cloud paintings,” creates a new cartography meshing formats: from prison window to Instagram frame. The artwork is produced by the artist in an incessant layering of paint and meaning; likewise, for my text, I had to refocus divergent trajectories of visual and philosophical enquiry, all the while cleaving to a limited word count.

Weeks after the essay was published in mid-2022, I remember receiving the news of a show Maire had in one of his dealer galleries featuring many of the works I’d seen in Rome, and feeling both so close (in my head) and yet removed from the circulation of that body of work, which the artist had produced in his year-long residency at Villa Medici. Ten years from now, I wonder if any of, say, the T-shirts Maire made during that time will still be in the world; I wonder, also, how Maire’s artwork or my essay will be interpreted then. One possibility is that the future “cloud” development might erase both my and the artist’s authorship and make unintelligible the philosophical, art historical, and contemporary references embedded in the text. But I can hope that mutating circumstances could make a way to unforeseen readings, other codes to crack, and a fresh logical quest for artist and author to share.