After being featured in both the 2012 Whitney Biennial and the New Museum’s Triennial, the young artist and filmmaker Wu Tsang is set to enter the art world at large in a big way. His film Wildness (2012), which was featured in the Biennial, documented a recurring party Tsang and his friends held at Silver Platter, a legendary bar in the MacArthur Park area of Los Angeles that had been a center of Latin and LGBT communities since the early 1960s. Wildness operates as a documentary while also artfully inserting fantastical elements into its concerns with the party’s place in the bar and the broader issues of transgendered life. Though performative and fictional, Tsang’s two new pieces on view at Michael Benevento in Los Angeles aptly address the sociopolitical as well as interpersonal relations within a community. These relations are frequently explored through performance and the performative nature of narrative film, and this witty melding of fact and fiction itself functions within the artist’s intention and desire to explore how the “narrative” functions in relation to “real life.”

Mishima in Mexico (2012), a film produced collaboratively by Tsang and his scriptwriter Alex Segade, draws inspiration from Yukio Mishima’s 1950 novel Thirst for Love. Set in Mexico City’s modish Camino Real Hotel, a writer and director rent a room in order to work through the creative process, melding Mishima’s fiction into the performative nature of their work (and lives). Tsang cleans the couple’s “house” costumed in a kimono, while a monologue addressing love provides the soundtrack. The struggles of work and love are prevalent throughout the film, and reiterating this is a scene in which Segade is shown running laps, again accompanied by a poetic monologue. The programmed, color-changing LED lights placed beside the video evoke a club atmosphere and create a chameleonic space, further inscribing a sense of performativity into the gallery itself.

Tied and True (2012), the other work on view, is a collaborative effort as well, co-directed with Ghanaian filmmaker Nana Oforiatta-Ayim. Set in a fictional postcolonial city, this shorter video also deals with the classic narrative of the struggles of life and love, albeit tinged with the conflicts created by social prejudice. Again, the script takes its cues from an existing film, this time Douglas Sirk’s All That Heaven Allows (1955), the melodramatic American equivalent of Mishima’s novel (in both, older women fall in love with younger gardeners). With Tied and True, we see Tsang addressing broader social issues and how behavior is largely constructed by the dictates of society. Once more, the aesthetics of cinema play an important role in translating the piece’s sensibility and themes. The settings are highly artificial and the colors in high contrast, reflecting the film’s theme of interracial love: in one scene, a conversation between lovers is held against a striking background split between yellow and blue.

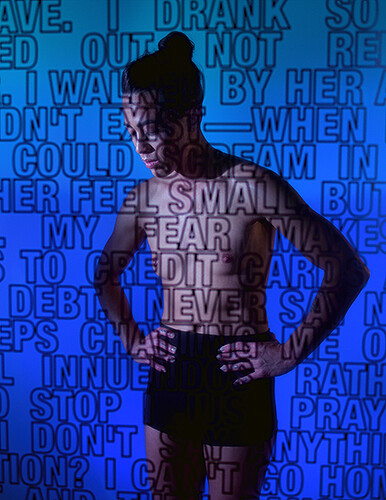

The photographic works on view in the exhibition are derived from a performance that took place at The Suzanne Geiss Company gallery in New York, in which audience members were invited to cut Tsang’s hair. With this performance, Tsang surrenders himself to the communal, while freeing himself “from a certain gender presentation.” The photographs themselves are dramatic yet poetic, the artist’s silhouette exposed and elaborated upon by text fragments on the wall. Psychologically charged, the photographs evoke the artist’s own taut tussle “with the subject of myself as a performer.”

Alongside the photographs are wall texts that read like diary entries; in fact they stem from a screenwriting exercise in which the author is encouraged to write down whatever comes to mind. Here the “automatic writing,” like the films’ subject matter, crosses broad stretches of reality and the imaginary, recounting social relations (romantic and otherwise), personal impulses, emotions, and anxiety.

Like Tsang’s aforementioned performance in New York, the works on view in the gallery (both collaborative and independent) take their cues from broader social engagement, yet are framed by potent shifts into the personal and psychological realms. Thus, while retaining his interest in the specific problematics of the lives of transsexuals, the show is a conceptual departure and progression for the artist, where the personal is indeed transposed into the political in ways that continue to engage and inform.