“You gotta love Jack Pierson” begins the flagrantly winking press release the artist wrote for his latest solo show, “The End of the World” at Regen Projects’s new palatial quarters located squarely in Hollywood, California. A literary effort, the statement morphs the typical promotional details of an artist bio into entertainment business buzz: previous exhibitions are described as “comeback attempts,” relationships with large galleries as “big budget studio roles.” Pierson’s rise to commercial success and (having out-earned contemporaries like “It-girl Nan Goldin”) his subsequent expulsion from the upper echelons of art discourse—the gatekeepers of which he refers to as the International Cultural Elite (ICE)—are chronicled here with a well-reasoned paranoia.

He claims, paradoxically, in the third person, that the artist is “oblivious to the fact that museums and art journals had long since slammed the door in his face,” concisely outlining his critical dilemma with the following: “his early downtrodden exercises in blitheness seemed to speak so lyrically about lost youth, AIDS, and Beauty that we became blind as his overpowering self obsession morphed into a topiary of empty cultural signifiers.”

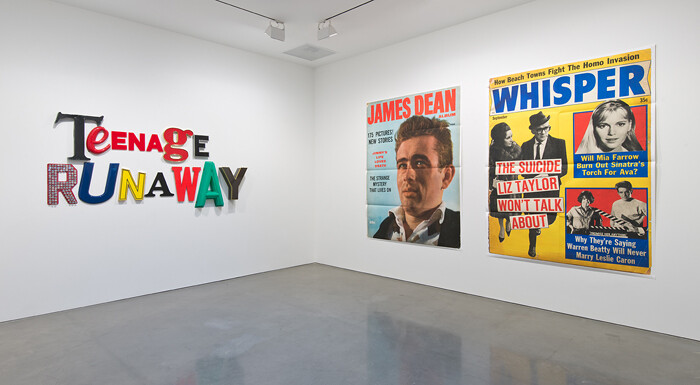

Self-deprecating and clever, that summary may ring true to many. The truth is, of course, you don’t gotta love Jack Pierson, especially if you count yourself among the chilly International Cultural Elite. You might find his signature sculptures to be too decorative, or sentimental, or too easily made to order—even if they are often successful in mining the evocative terrain of American nostalgia. There are several of this type of sculpture on view here, cobbled together from repurposed elements of forlorn signage, spelling out the glib highs and lows of stardom—“A TRIUMPH!”—“SAD”—and perhaps the existential synthesis of a life onboard the roller coaster—“MOTHERFUCKER.”

But the words that rightfully hog the spotlight are executed in a different mode. Cutting diagonally across the entirety of the main gallery are monolithic, three-dimensional letters made of silver spray-painted particle board: “THE END OF THE WORLD.” In font and scale, they are an appropriation of the Hollywood sign, letters that—better than any building—monumentalize the spirit of Los Angeles. A doleful song loops on a plastic phonograph on the ground and a large, unusual painting hangs on the opposite wall: an extreme close-up of Little Richard, blanched, eyes and mouth wildly wide open, evincing an anguished star quality.

In light of Pierson’s artist statement, what comes to mind in this room is the superhuman dehumanizing effects brought about by the successful branding of an artist. These frustrations seem to be channeled into an earnest, nihilistic embrace of spectacle, which, in the context of a big fish commercial gallery, tells a story of life in the golden cage that is more engaging than the sum of its parts.

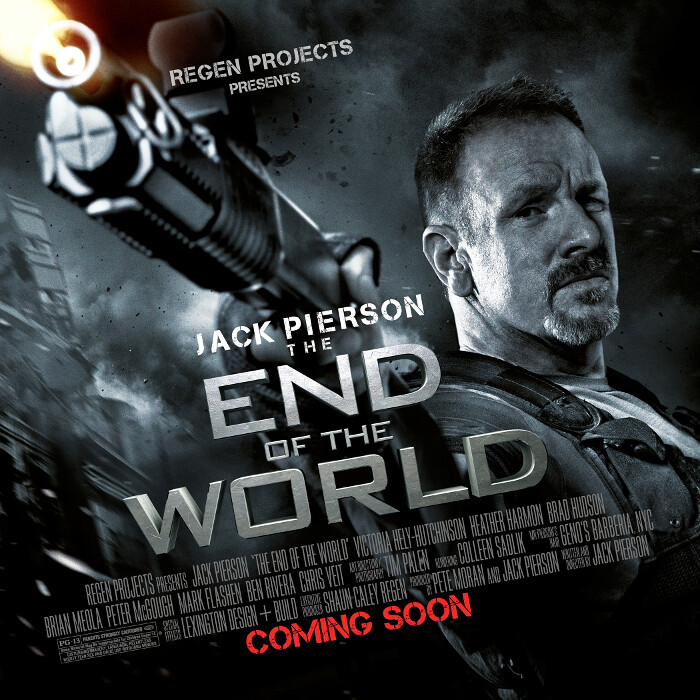

Lending corporate gravitas to the exhibition’s extensive conceptual wrapping is a poster photographed and designed by Lionsgate’s Chief Marketing Officer Tim Palen. Done pitch perfect in the style of a post-apocalyptic action blockbuster, a brooding Pierson aims a long barreled automatic weapon into the foreground and fires away. Again, “THE END OF THE WORLD,” skewed and silver, floats on the surface of the image. Below it there is a roll call of production credits: gallery staff, etc.

Riddle or gag, that the artist does not unravel the age-old quandaries of the art market here is not, after all, the end of the world. Questions are generally more productive than answers anyway. However, exactly what is being asked is certainly not crystal clear. The most interesting elements of the show deflect from the actual work on view, with the exception of the solid slogan writ large in the center of the gallery. The ways and extent to which the production is inflated press against the boundaries of an artist’s customary place in situating one’s practice for public consumption, and that’s a promising new role for Pierson.