Middlebrow. Middle America. Middle manager. Middle-of-the-road. Middle-age. Middle-age spread. Middle of the day.

The middle is disappearing, or as one prophetic poet put it, the center cannot hold. But it does, sort of. John Miller has placed his finger on it, holding it down like a loose sheet of paper that might blow away.

The middle, for Miller, is most clearly captured in a relatively deadpan photographic project that involves snapping places in the middle of the day. The middle is that soft vague part of anything, the flabby beer belly, the gooey center. Generally the middle is the most reviled. Hated by both the bottom and the top. When Virginia Woolf wrote about high, middle, and lowbrows in a letter published in The Death of the Moth (1942), the highbrows had a fierce commitment to beauty, value, integrity, and the lowbrows committed to the intrinsic pleasure of the physical; both were worthy of praise, but not the middles, who in their pursuit of social rise were only appreciating that which others told them to appreciate, their real pleasures the guilty kind, schlock really. One of the regular gripes heard around America these days is about the erosion of the middle class and how terrible that is. But the middle weirdly holds, for now at least, here in the middle of the day.

Miller has taken one snapshot from his series “The Middle of the Day” (1996—) and wallpapered it larger than life in one of the corners of the gallery of an urban middle-class highrise (not far from a garbage pile in the picture plane). Two pieces of plywood furniture malinger, not far away in the gallery itself; they seem like so many sticks of furniture seen curbside in the middle of the day, their long cheap lives ending abandoned in the street, the last owners either carelessly trashing the neighborhood or vaguely hoping that their junk might be another’s treasure.

These two, a side-table and a dresser, cheaply made as they may be, are still shiny and new even if knocked over and abandoned looking with the their middle-of-the-day black-and-white backdrop (always from 12—2pm). They are accompanied by a perfectly clean plinth, ready for a monumental horse-and-soldier statue, but remaining metaphysically clean, a pristine leftover prop from a lost de Chirico painting.

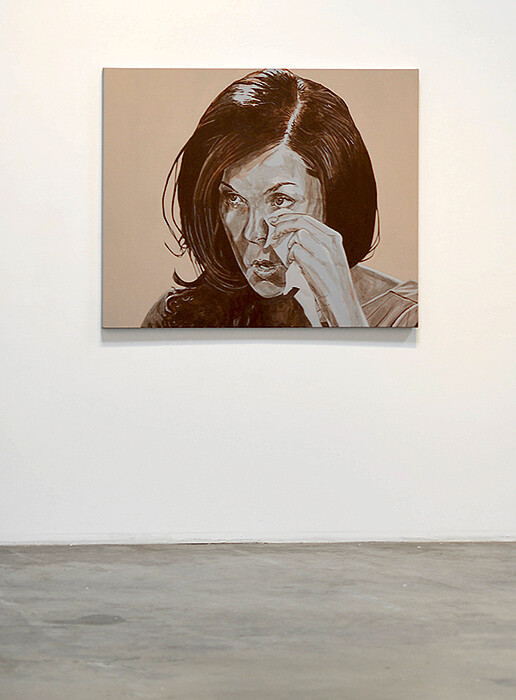

The big, vague middle isn’t just backdrops and accoutrements here. Miller has lovingly painted with a limited palette a cast of reality television performers all weeping. These emoters performing themselves performing breakdowns with weepy theatricality have perhaps cut a tidy career for themselves. Questions then begged: do we need public emoters, reality TV stars, and Republican politicos (cue US Speaker of the House John Boehner)? Is their release just sentimental drivel exponentially jacked up for effect or public catharsis, them weeping where we cannot? Or like Speaker Boehner, who famously cried about creating opportunities for working people and who has consistently voted against ever actually giving those people any opportunities: is their weeping just a big lame show, crocodile tears? In painting these lachrymose entertainers, Miller makes them both mutedly handmade and uncomfortably more important, paint being softer, more physical and grander than the crisp clarity of a photograph these days. Somehow the artist cuts together the high and the low with this raft of paintings, and we end up back where we began, in the middle. Thank you, John Miller, for documenting with bathos and pathos, this disappearing middle, reviled ever as bourgeois strivers, the soft core, the center that at the very least cannot seem to hold its tears.