Eileen Quinlan’s second exhibition at Overduin and Kite explores an array of departures from the old tricks of her “Smoke and Mirrors” series (2004–2007): signature photographic still lifes of colored light passing through said materials, capturing all the flecks and blemishes that mar the ethereal compositions with engrossing, analog textures. Quinlan’s fascination with photographic mechanics and accoutrements continues here, and like the tableaux through which she has established a self-reflexive discourse on image-making, the discrete elements of this show collude as a carefully scattered puzzle.

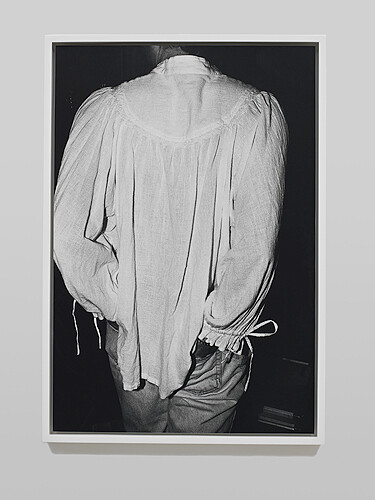

To begin with the oddest inclusions, there are three black-and-white photographs dated 2011 but which the artist shot many years ago when she first took up photography: Sisters of Mercy, depicting the rough granite contours of the castle walls of a former convent near her New England childhood home; The Pond, a back-of-the-head self-portrait in which the artist’s figure slips into surrounding bog brush; and Paul as Poet, framing the back of a man in a white tunic and jeans. These images set the tone for subjective excavations, tunneling into matters of difference and repetition not with regard to seriality as much as context, and, specifically, how re-situating images in different temporal and relational contexts alters their meanings.

The show’s title, “Constant Comment,” is borrowed not only from the still-popular 1940s brand of orange pekoe blended by the Bigelow Tea Company, but also from the title of a large print of a white quilt which is the exhibition’s central figure. The pattern of the quilt maps a triangular motif of hard angles, reminiscent of the artist’s stacked mirrors and their slanted reflections, and, more obliquely, perhaps of the softness of the cloth in the aforementioned poet’s shirt. This photograph also begins a series for which the artist has employed a batch of aged, large-scale, black-and-white Polaroid stock whose chemical decomposition causes erratic faults and absences in developed pictures.

But in Constant Comment (2011), the image is largely intact. Only the bottom right edge is seared black, stitched to the photographic likeness of the quilt by tendrils of light. These stringy bits are actually chemical traces occurring in the liminal area between imprint and void; nevertheless, at first glance they look more like threads unraveling from the antique blanket, and in Forgetting (2011)—a more vastly corroded picture of ferns—they can be mistaken for botanic ornamentation, while the actual outlines of foliage are beneath, riddled with cavities that obstruct their view. Other more abstract works, like Portrait of Space (2011), call attention to the visceral materiality of the scratched, streaked, and erased film stock.

In a recent series Quinlan re-photographed identical stagings of mirrors, etc., but with different lighting palettes and arrangements. For Creep 1 and Creep 2 (both 2011) she has repurposed the same shot of the quilt in Constant Comment as a canvas primed for iteration. Then, there are the most familiar pieces—kaleidoscopic, saturated with refracted light and color—mirror still lifes that signal an unprecedented turn in the artist’s practice for the fact that they feature subjects other than themselves. In Cock Rock (2011), a red bow tie triples across the frame and a twenty-dollar bill wafts around in a background of greens and golds. The two triangle shapes that come together to form the bow tie are proportionally similar to the triangles dotting the recurring image of the quilt, further webbing formal associations whose ultimate significance is vague, but touches on synchronicity, which in turn points to time.

Quinlan’s methods are predicated on the construction of coincidences, from binding transient placements and vantages as photographs, to curating their constellations for presentation. One final piece, Crazy Quilt (2011), fragments the colorful triangular patchwork of a different quilt than seen elsewhere. Its design is only visible in the three panes whose reflections strike directly into the camera lens (rather than ricochet among themselves). Each view is in foggy focus, bounded by the dusty glass’s crisp edges, two of which meet at a chipped point. Is that imperfection a post-human memento mori? The surrogate hand of the artist? A fractal of visual glitches? On the surface it’s a happenstance flaw, and these photographs are all surface, densely compressed. Quinlan’s interest in artifice has consistently been an avenue for looking at its behind-the-scenes actuality. Rather than critique the facades and fetishes these simple apparatuses—old film, mirrors, appropriated images—effect, she exploits them herself to create theater, an emotive art, and an exciting terrain for manipulations.