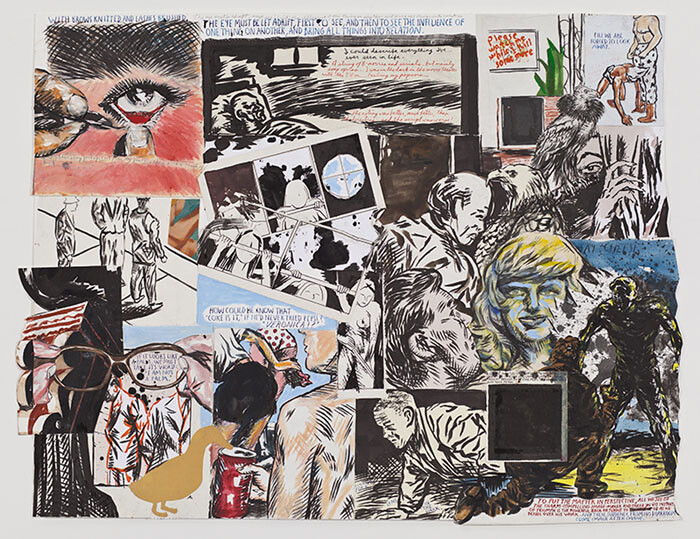

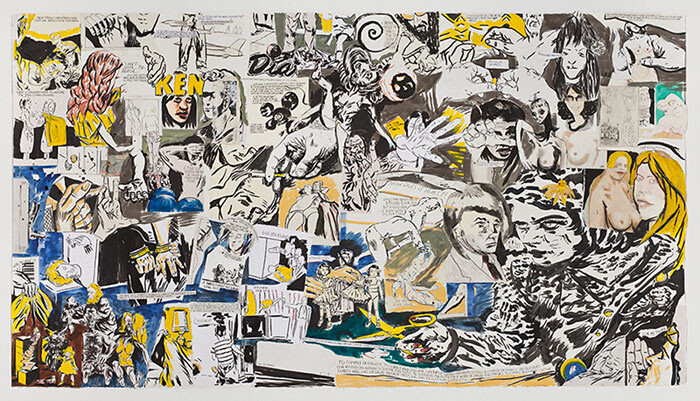

All the gang is here. An open-mouthed munchkin, mouth pitched back in roaring vavoom, the Reagan-headed claymation adventurer Gumby, weird scientists, weirder hippies, butch baseball players, and a gang of distant surfers sliding down the faces of pristine blue curls, most of it accompanied by the clipped noir narrative and untraceable quotations of Raymond Pettibon’s scattered story, the one he’s been writing for decades. Not every piece contains an old character though, and there’s even an unfamiliar stage: a clutch of collages occupy part of the exhibition, curled edges of layer after layer, old ads and celebrity snapshots, battered Valentines and newspaper clippings, but mostly just drawings layered on drawings, some stripped and simple, others spooky and complex, all of them an all-over-the-place mess.

But there’s something about looking at a new exhibition by Raymond Pettibon that is always like looking at an exhibition by Raymond Pettibon. In a first blushing witness of the work, the language, the voice was all there, and this last viewing finds the same: the pitched-punk anger balanced against something altogether fragile, heartbroken, and literary. The visual language is like that of a cartoon that’s wandered far from its comic book origins and found an oasis where Egon Schiele nudes trade baseball cards and read hellfire religious tracts chock-full of hard-luck stories, good Christians falling prey to hippie Satanists. Since its public inception under the banner of SoCal punks Black Flag, Pettibon’s distinct visual style has grown older, stronger, the lines so confident that even when reckless are still inimitable (though many try). The style has not grown less thrilling in its familiarity. Pettibon is still like a good punk record, even if he’s managed a nuance and subtlety that was never punk.

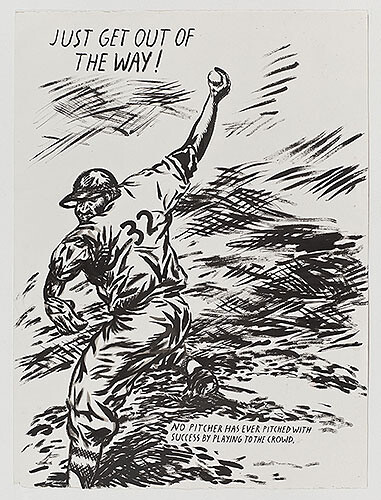

This exhibition is even more like looking at an exhibition by Raymond Pettibon than the previous ones. Pettibon winks at us with his title, “Desire in Pursuyt of the Whole,” a curious misspelling of a Frederick Rolfe (the self-proclaimed Baron Corvo) novel that like many of Rolfe’s novels is a thinly disguised autobiography, this one starring a stand-in named Nicholas Crabbe. A would-be priest and practicing homosexual, Rolfe had a particular talent for invective, aided and abetted by a vocabulary that broke three of my dictionaries—only the Complete Oxford did not shudder and crack under the force of his personal lexicon, aggressively obscure and often wonderful. I suspect snatches of prose from the novel find places in Pettibon’s collages, though currently unverifiable, but the real trick of the show is almost that the artist has been playing his own version of Corvo/Crabbe. It’s as if Pettibon has taken his vast archive of words and pictures to play some meta-role in an interlocking and difficult-to-trace autobiography of imagery. Pettibon is playing Pettibon for us (the name Pettibon, like Corvo, is also a nom de plume). But the illusion of clarity in this game gets violently scrambled in the chaotic collages. An autobiography, veiled in erudite fiction, held together by vituperation is the form of Rolfe’s novel and perhaps the form of this exhibition that shares its name. Pettibon’s invective has long been against the curdled fear of perceived fascism and its economic arm, unfettered capitalism, as the artist has made clear in any number of interviews and works. The artist’s talent for highly critical language is best hinted at in the poster for the exhibition, handmade by the artist and hanging as a work of art at the front of the gallery. Amidst a collage of drawings and scraps of ephemera, Pettibon has written in the artist’s signature lettering: his name, the gallery name, the address, the phone number, and if you keep reading, the web address written as www.regennomicsprojects.com.