A recent billboard project in Los Angeles featured an image of a shirtless black man (the artist Kori Newkirk) on a white background, his mouth stuffed to bursting with a snowball. LA Times critic Christopher Knight observed that it looked like a ball of cotton, thus in some ways conjuring up the history of African-Americans as slaves in Antebellum cotton fields, as well as the systematic censorship of black people ever since. The naked torso, the mouth stuffed not with cotton, but a snowball, suggests something, however, a little different—the sexual practice known as snowballing, which includes a man having his semen spat back into his mouth after a blowjob, gay or straight.

In his current exhibition at Country Club Projects—a boxy Rudolf Schindler house in Mid-Wilshire built in 1934—Newkirk continues to use himself as the nexus of the body politic and desire. In what might have been the living room of the house-cum-gallery, the artist layered about one hundred white t-shirts into four overlapping tiers on the black floor into a full circle with an empty center like an oculus (Mayday, 2010). Formerly worn by the artist until they began to gray and stain, the t-shirts had a second life (en route to their third in the gallery) as a way for Newkirk to clean the grimy floors of his downtown studio. Striped and stained with the deep black muck of the studio floor, the t-shirts are crisscrossed with tiger stripes. Arranged just so, the associations with labor and the interplay (charged as it is) between black and white are less obvious those of the muscle-bulging male models in t-shirt ads dotting this great land.

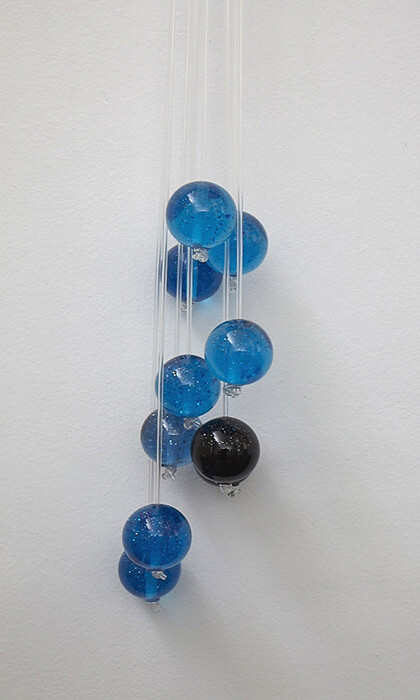

Another more formal work in the show, Boiler (2010), has the same yen for physicality: a clear plastic hose is woven around rows of shower bars arranged like a zipper, with a handful of blue balls and one black one dangling suggestively. Indeed, the nouns in that description can’t help but be suggestive: showers, bars, zippers, hose, balls, though their trappings give it the institutional flavor of a prison or hospital.

Blackness for black artists will be an issue so long as we live in a place where being black is still an issue. And I wouldn’t want to pigeonhole Newkirk as a “gay” anymore than he’s a “black” artist: both smack of a tiredly didactic identity politics. Refracted through the lessons of Conceptual art and coming at the ass end of identity politics (as one of the first young artists to be dubbed “post-black,” a phrase that has dogged the artist for years), Newkirk’s practice is smart, sexy, and black, without being overly defined by any one of those elements. In Mayday and Boiler, Newkirk infuses these objects with a physical longing, objects which might only achieve solace in the process of his making them.