A strange symphony of ting-tong sounds echoes through Dong Feng in Jiangsu, roughly 450km north-west of Shanghai, when we arrive. In the background, a snaring sound of power tools cutting and sanding wood. Ting-tong. We are in front of a four-story office building owned by Han Sun, one of Dong Feng’s 4,725 villagers. After a visit to IKEA in Shanghai ten years ago, the thirty-six-year-old Sun set up an online shop in the once-sleepy village, combining IKEA’s flat packing efficiency with more Chinese inspired designs. Sun sells his flat packs through Taobao, Alibaba’s Chinese marriage of Ebay and Amazon. Sun’s immediate success, the first of its kind in Dong Feng, inspired two friends to start their own Taobao shops, also making and selling flat pack furniture. When we arrive in Dong Feng in the spring of 2017, the number of Taobao shops has increased from the initial three to nearly 16,000, with an average density of more than three per capita, the highest in China. Dong Feng used to be home to a few farmers, a modest group of pig breeders, and a local waste recycling industry. Today, it offers more than 35,000 jobs related to Taobao commerce, with a turnover of 493 million RMB (63 million Euro) last Singles’ Day, the largest offline and online shopping day in the world. Dong Feng is a Taobao village. Ting-tong.

The “Bed,” Dong Feng’s Taobao bestseller, with more than 433,000 units sold in one year. Photo: Song Yu, AMO/CAFA.

Sun

The elevator brings us to the third floor and opens to a 200m² open-floor with the messy appeal of a Silicon Valley startup. The ting-tong sounds further intensify with a crowd of young workers processing orders, texting with clients, and refilling inkjet printers that are spread over several desks churning out IKEA-like instruction manuals. We are greeted by Sun himself. According to Song Yu, our Chinese collaborator, the handsome Sun is clearly prepared and media trained. We ask him how he is doing. “The situation is delicate, very, very delicate. The competition is very strong and the emphasis on cost reduction is making it difficult for everyone to make profit.”

Taobao.com was launched in 2003 as an easy-to-use platform for local producers to create e-shops and sell their goods directly to customers across China. Taobao offers a wide range of products from electronics to furniture and local produce. After initial success in cities, Taobao sales have more recently accelerated in the countryside. In recognition of this growth, rural areas with a certain concentration of online shops and a collective ten million RMB turnover qualify as a Taobao village, which provides the village with additional support for training, marketing and expanding the infrastructure connected to the platform. Dong Feng, now known throughout the country for its furniture production, is one of the first Taobao villages in China. The success of Taobao is fueled by the Aliwangwang messenger app, which allows consumers and producers to talk directly and customize their orders, shaping them to their exact needs. And with every message that goes back and forth it goes ting-tong.

Sun’s design unit on the ground floor with eight designers adapting templated designs for clients and refreshing the e-shop. Photo: AMO/CAFA.

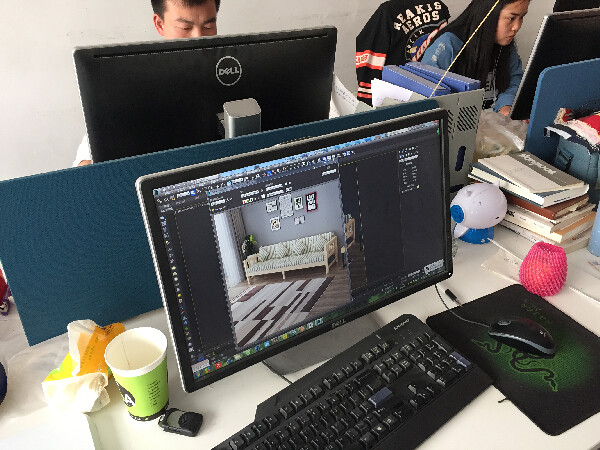

We visit Sun’s photo studio on the second floor where he shows us his latest furniture line. He has mixed feelings about it. He proudly presents his new Scandinavian vintage look collection, made from more precious North American wood and thus carries a relatively high retail price. The dressoir trades for 1,590 RMB (around 200 Euro), which is roughly equivalent to Ikea’s generic BESTÅ series TV furniture in China, but no match for cheap Taobao alternatives that go for less than 500 RMB. Sun invested heavily in the new line, but sales are weak, and he seems to be losing money. Asked about his future, Sun shies away, saying that he is too preoccupied with everyday concerns. After quickly walking through the ground floor workshops where most of the production takes place by middle-aged men and women, cutting, sanding, and plastering, our last stop is the design department. Housed in a small booth, separate from the production area and packed with computers, design is practiced in an eclectic fin-de-siècle way with around ten people actively mixing existing templates and molding collages together in 3dsMax, reshaping the online shop almost in real-time and for individual customers. Sun’s shop seems to be doing what 3D printers were supposed to be doing by now: customized design for the masses.

Village

Sun drives us down Taobao Road to the Party Secretary building in his new, but dusty BMW 7 Series for a meeting with the deputy secretary of the village. We hope to resolve the lack of accurate sources for documenting the development of the village for our CAFA research studio focused on the future of the Chinese countryside. Dong Feng’s furniture production industry began as a home-based enterprise, with early factories emerging from within the traditional courtyard houses. Rapid economic growth led to the construction of multistoried factories attached to the houses. Most of the factories, like Sun’s, sprung up along Taobao Road, which today resembles a deconstructed version of IKEA, with small and medium sized factories continuously consuming large heaps of wood and releasing cardboard flat packs waiting to be picked up.

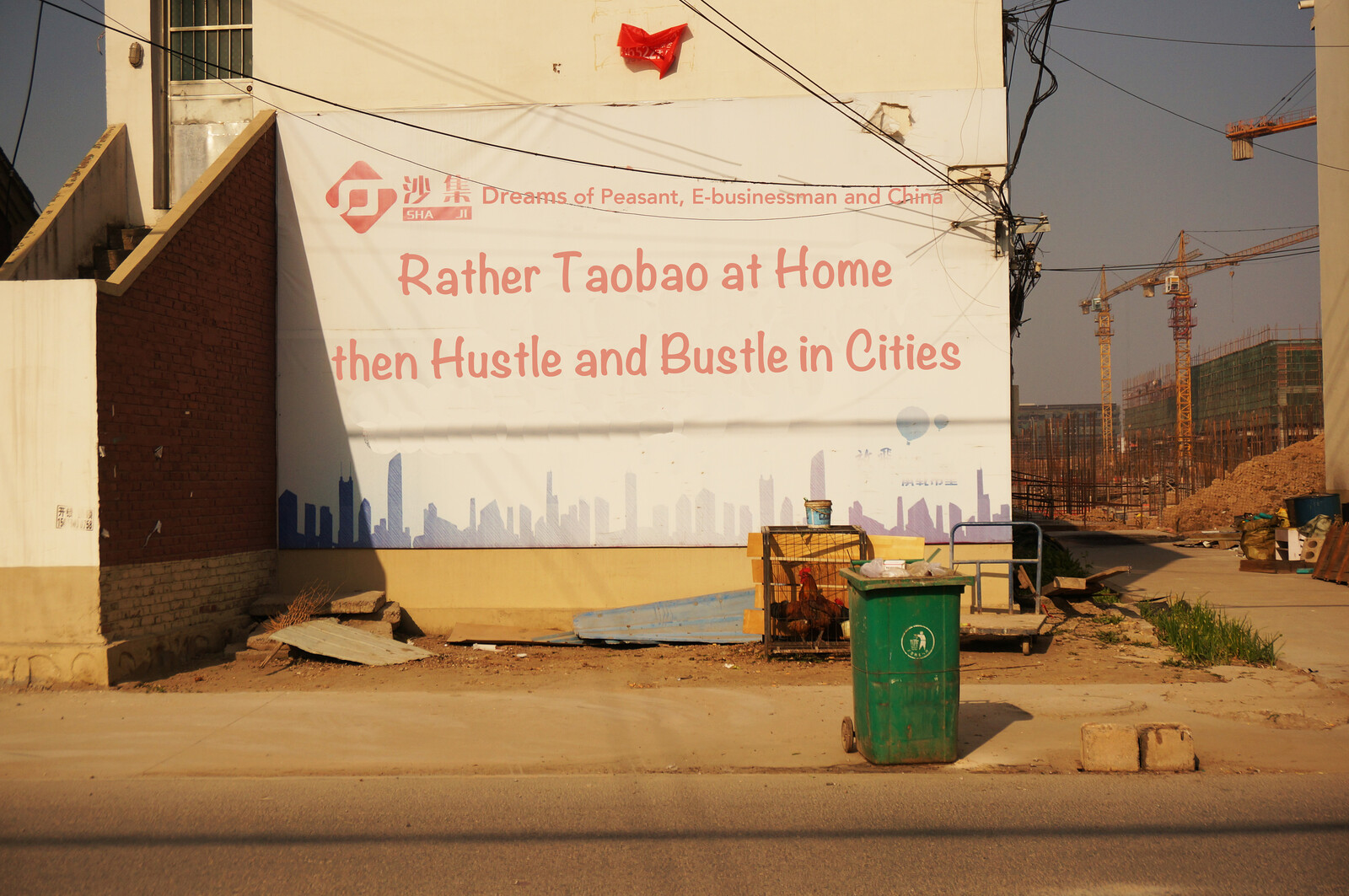

Becoming a Taobao village increased local government support and led to the construction of larger factories resembling maker spaces on speed. We pass young people smoking cigarettes and spray painting table parts. The average age seems to deviate from the cliché of dying villages. Dong Feng is rather young, with a considerable amount of people having come from nearby villages. The village is plastered with slogans like “A Pleasant Wealth Miracle, easy like a Trifling Matter,” “To be Rich, E-commerce leads the way,” and “Put down the hoe, pick up the mouse.” Many slogans promote equal rights and are gender sensitive, like “Women are powerful, busy with Business.” Compared with Facebook’s “Move fast and break things” or Amazon’s “Invent and simplify,” Taobao’s propaganda seems more socially considerate, “inclusive,” and optimistic.

HQ

At the secretary office, the deputy secretary enthusiastically greets us. We are apparently the first foreigners to visit the village since a Norwegian merchant visited five years ago. When we arrive, a large meeting is taking place. We can’t attend, but we are told it is about discipline. Song Yu interviews the deputy leader on the development of the village. We discuss how to make a new and up-to-date map of the town and the secretary starts to hand sketch the latest developments. Dong Feng is like a mini-Dubai during its most intense phase of construction: growing too fast to record.

Afterwards, Sun takes us to the rural e-commerce HQ, a large multistory building built as a joint effort between different local administrations to showcase Dong Feng’s progress and success. A young lady guides us through the 2000m² showroom filed with Dong Feng’s products, infographics, and photos of visiting dignitaries. The central item in the exhibition is the village’s best seller: a bunk bed, also known as “The Bed,” of which last year alone, Dong Feng sold 433,000 copies.

Charts on the walls show graphs with logarithmic growth, with a propagandistic quality similar to tech companies at home. They echo Alibaba’s image of a glorious future for Taobao villages: “It was another magnificent year. Internet is getting into the rural areas in China at an unprecedented speed. Given the background characteristic of the times, Taobao villages throughout the country enjoyed three favorable conditions—platform encouragement, government support and industry demand, and entered the ‘golden age’ featuring faster growth.”1

In the back of the exhibition room there is a huge model of Dong Feng’s newly planned expansion, which both private and public parties are feverishly building. It is a strict modern plan where all different aspects of the new Taobao economy are separated into distinct clusters for logistics, production, research and investment, and living. The plan also introduces large infrastructure upgrades, including a high-speed rail connection. The goal is to showcase what is dubbed the “Dong Feng Model,” and the masterplan should largely be ready for a Taobao Symposium in 2018.2 Organized in distinct programmatic clusters, the new town looks sterilized and archaic, avoiding all of the ad-hoc qualities of the existing fabric that led to Dong Feng’s success in the first place. None of the frivolous interactions, ting-tong chimes, or courtyard houses, which propelled the initial growth, are to be found. Where Taobao initially broke with Fordist production, the new Dong Feng is still weirdly Fordist in plan.

Taobao Future

With signs saying “do not photograph” posted everywhere, the village feels like a classified military zone. Secrecy thrives. Sun hinted to this, that the success of some has made neighbors envious and fueled a fierce competition to cut costs, degrading not only the quality of production but also the environment. Like other internet customer-to-customer (c2c) platforms like Uber, Dong Feng is suffering from a race to the bottom. Social cohesion in the village is under pressure. Successful products are immediately copied by others, which leads to the same product being offered in different versions by dozens, if not hundreds of different Dong Feng shops. Affluent Chinese are increasingly avoiding buying products on Taobao because of their high chance of being “fake” or simply of poor quality. Instead of selling what is unique, Taobao shops sell what is popular, and by saving on costs, they undermine themselves. As the platform is run into the ground, the slogans motivating people around town change light.

Taobao villages harken back to many of the virtues the internet promised in the early 1990s: decentralized spatial hierarchies and flat networks where only infrastructure, organization, and connectivity count. Last February, several high-ranking Chinese government officials presented their vision for the countryside to our studio in Beijing. They acknowledged that a considerable part of Chinese cities suffer from poorly copied Western concepts, and claimed that the “true” China can only be found in the countryside. This was echoed in President Xi Jinping latest address to the National Assembly in November this year, when he announced the countryside to be the number one state priority, developing national plans for quality of life improvements and expanding sustainable economic production.3 In all of these plans, the internet will be crucial—and Alibaba the government’s main partner.

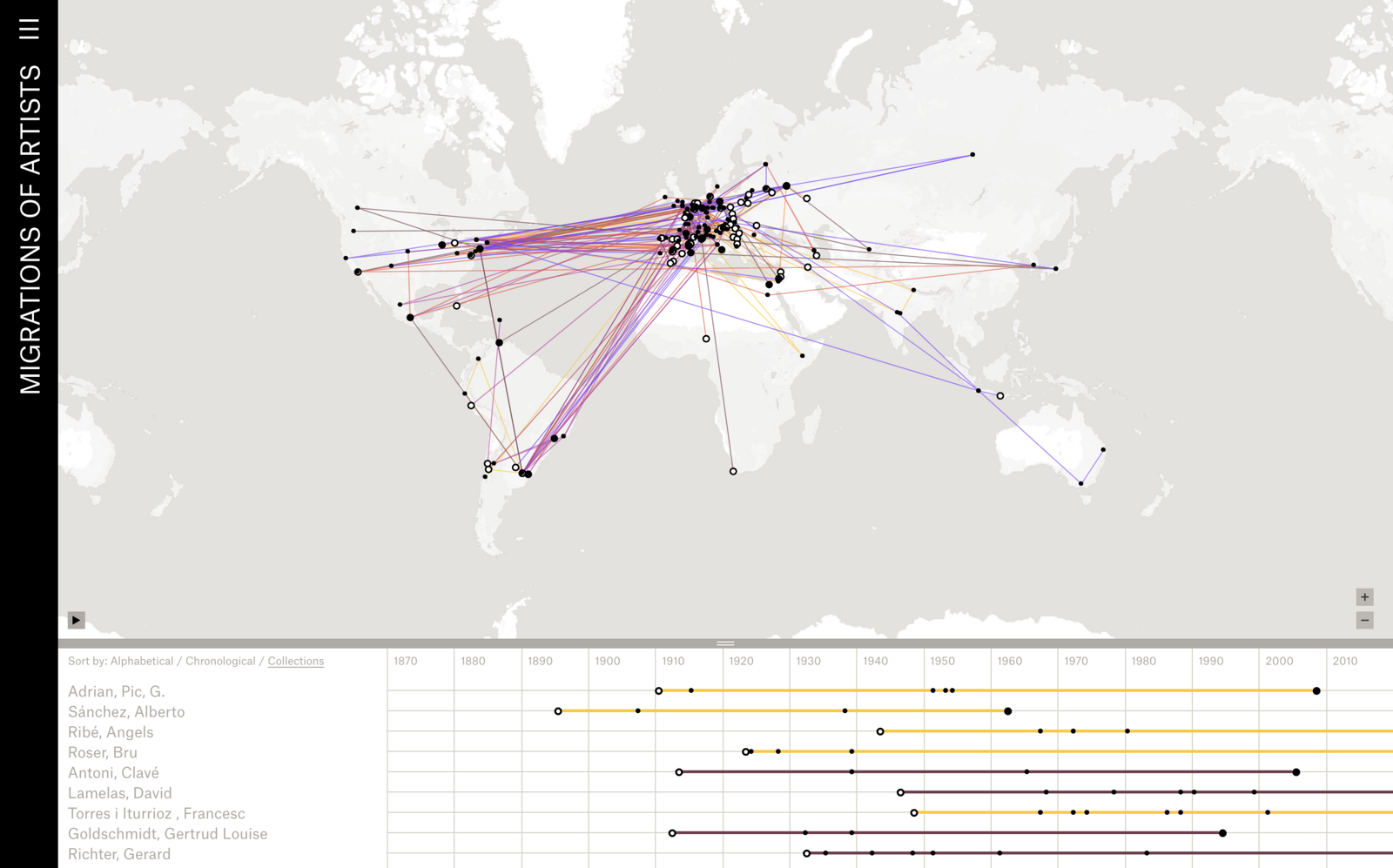

Alibaba’s Strategy for Rural Areas. Source: AliResearch.

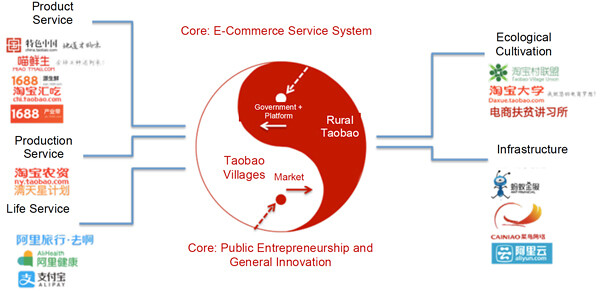

The Chinese government has largely retained the power to shape its internet the way it wants. While many aspects of The Great Firewall can be criticized, it also introduces some opportunities to serve its people that are unavailable to many Western countries who are at the mercy of a few big platforms. While the development of the Taobao villages was largely dependent on grassroots initiative, Alibaba has been developing a secondary branch of its operations called rural Taobao, with thousands of small countryside outposts called service stations. In a report from 2015, Taobao defines this strategy as “Dual-Core +N.” The rural Taobao branch collects data from these stations which feeds into government programs for planning and infrastructure development, primarily in poorer areas. State-funded infrastructure leads to further growth of the platform, and boosts the overall economy. This pairing of state and private initiatives encourages Taobao to create new markets in places that are less economically viable in the short run, or even undertake non-profit driven development.

It is clear that there are also opportunities for Taobao to balance the winner-takes-all logic driving big platforms in the West, as well as other parts of Alibaba itself in China. In many ways, Taobao presents an alternative to the tax-break economy.4 Within the Chinese economy, Taobao can be an instrument to challenge relentless cost reduction and optimization and instead turn it into a more citizen-oriented alternative that serves the needs of the entire state. It can move beyond algorithmic manipulation for short-term shareholder profit to serve government agenda’s—in essence, an actual sharing economy, or what might have once been referred to as communism.

The combination of the state and the internet in China leads to a paradoxical conclusion that in order to fulfill the potential of the internet and create new forms of autonomy, we need authority. The development of Dong Feng presents a first step towards a new and experimental mode of urbanism; a place where one could break with twentieth century of planning. Seeing as how organization, production, storage, and distribution are all done from the countryside, the traditional position of the city as a hub can be drastically reconsidered. Whereas everything currently revolves around cheapness, it can also revolve around the community, enjoying life outside of, as well as in the city. Ting-tong.

“Research Report on China’s Taobao Villages,” Ali Research (2015), ➝.

The creation of “models” is one China’s most effective, and desired, ways for describing prototypes to be replicated.

“Xi wants big data to make lives better,” People’s Daily English (December 11, 2017), ➝.

One clear and recent example of the tax-break economy is the recent Amazon HQ2 competition, with regions begging for investment into their rural areas and surrendering their public interest in exchange for creating a few cheap jobs.

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”

Subject

This article was written as part of the AMO/CAFA Spring 2017 Semester Countryside Studio by Stephan Petermann, Prof. Lu Jiping, Shao Jun, Shi Yang, Dongmei Yao, and Rem Koolhaas. The underlying research was done by Song Yu with further development with Yina Moore and Jiayu (Joe) Qiu (both Harvard GSD).

Urban Village is collaboration between e-flux Architecture and the 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB) within the context of its theme, “Cities, Grow in Difference.”