The April 1968 issue of the American magazine Progressive Architecture and the May 1968 issue of the UK Architectural Design journal both featured a thematic focus on matters regarding education and architecture. “The School Scene: Change and More Change” was Progressive Architecture’s cover claim, whereas AD asked: “What about Learning?” The cover illustrations of both magazines suggested a technological overhaul of the traditional classroom, with images of computers cut and pasted into a print of a Victorian classroom at Progressive Architecture and a small television set worn like a wristwatch at AD.

Instructional and communication technologies ranked prominently in both magazines’ reports and case studies from the intersecting fields of building and learning, of educational and urban planning, of spatial programs for a rapidly shifting landscape of knowledge production and acquisition. However, the notion of technology that appeared to be most sought after was technology in the sense of environment, consumerism, and mobility.

Cedric Price guest-edited the AD issue on education (and contributed the cover montage). In his editorial essay, Price made clear how he wanted the change in the school scene to be understood. He attacked “education,” once an institution of emancipatory potential, as having degraded into “little more than a method of distorting the individual’s mental and behavioral life span to enable him to benefit from existing social and economic patterning.”1

In the final paragraphs of his rant, Price admonishes architects to respond appropriately to a situation that requires a radical break with the established forms and structures of learning and education. Acknowledging the fact that learning can no longer be contained in four-wall units and limited to a particular period in an individual’s life, Price claimed education needs to be “re-thought.” This resonsideration was supposed to attend to the conditions of a social and economic reality informed by technological change and marked by the spatial and temporal ubiquity of learning. For Price, what’s key is the reformulation of the architects’ and planners’ roles, since their ideas of spatial flexibility, for example, don’t adequately respond to the particular time management and privacy needs of a contemporary teenage student. Thus, the architect’s task would be to provide an “individually operable space.”

Regarding the transformation of the educational realm, the editors of Progressive Architecture put a similar emphasis on the expansion and the urge to change the attitudes of planners and architects. Introducing their thematic focus, they first offer economic and demographic data about the annual $52 billion paid for education by the US government, the almost-seventy million students between the age of 5–24, and the approximately two million teachers needed to educate them.

The coupling of econometric and demographic data was meant to be indicative of a new role to be played by the educational sector in terms of the political economy at large. The systems of elementary and secondary education, the editors venture, are “taking on the attributes and responsibilities of civic leaders, sociological catalysts, and seminal agents for urban rejuvenation, as well as their traditional responsibilities for formal education.”2

Educationalizing the Social?

Like Price, Progressive Architecture asked for a “new thinking” as well as a redefinition of participation and interdisciplinary cooperation. Rather than programming separate schools in suburban areas, the journal’s editors argued, “the school must be worked into the community fabric, and must become a contributory member of the community, both to help and ameliorate its ills and to enrich it through involvement with its life and culture.” Repeatedly stressing the need for “involvement” was a way of saying that there was an alarming dearth of integration to be addressed by educational planning, or, using a more poignant terminology, that the social and political fact of segregation was education’s main object. “There is a feeling,” the editorial further tries to explain, “that education is being asked to purify all our national problems of racial injustice, violence, poverty, and hatred; to act as a sort of filter through which these impurities might be removed in the process of educating our children and involving their elders the process.”

In 1968, education was invested with the hope that it could take on a central role in social and economic change, to become the therapeutic medium to cure the nation’s disease. In the US, the protests and organizing of the civil rights movement and militant black activism made inevitable the acknowledgment of the imminent social and political crisis of the city caused by racialized urban politics, suburbanization, white flight, and so-called ghettoization. Thus, before, during, and after the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, the issues of race, class, and urban renewal were granted high priority on the agendas of public authorities and academic research in education, sociology, urban studies, and the like.

Looking for a response to the crisis of the city, education was considered the key remedying force, and with it the places and spaces of learning. If the analysis of neoliberal governmentality often refers to a depoliticizing “educationalization” of social problems, the governmental turn to education in the 1960s certainly preceded this contemporary tendency.3 The physical, but also the technological and social environment of education became the object of far reaching conceptual and planning activity informed by a reformist social and urban politics aimed at pacifying inner city unrest. At times, it even sought to heal the wounds of anti-black violence inflicted by municipal governments, their housing politics, and misguided educational policies.

AD and Price seemed primarily concerned with the reconfiguration of the spatiality of learning in the interest of individualized and, ultimately, “uncommitted” spaces of calm and potential self-education. Progressive Architecture was more openly looking for models of civic participation and the socially and economically generative role of education. However, the approaches certainly shared an interest in “nonpedagogical, nonadministrative educational programming,” as well as in the future roles of architects and planners in it.4

Abandoning the Schoolhouse

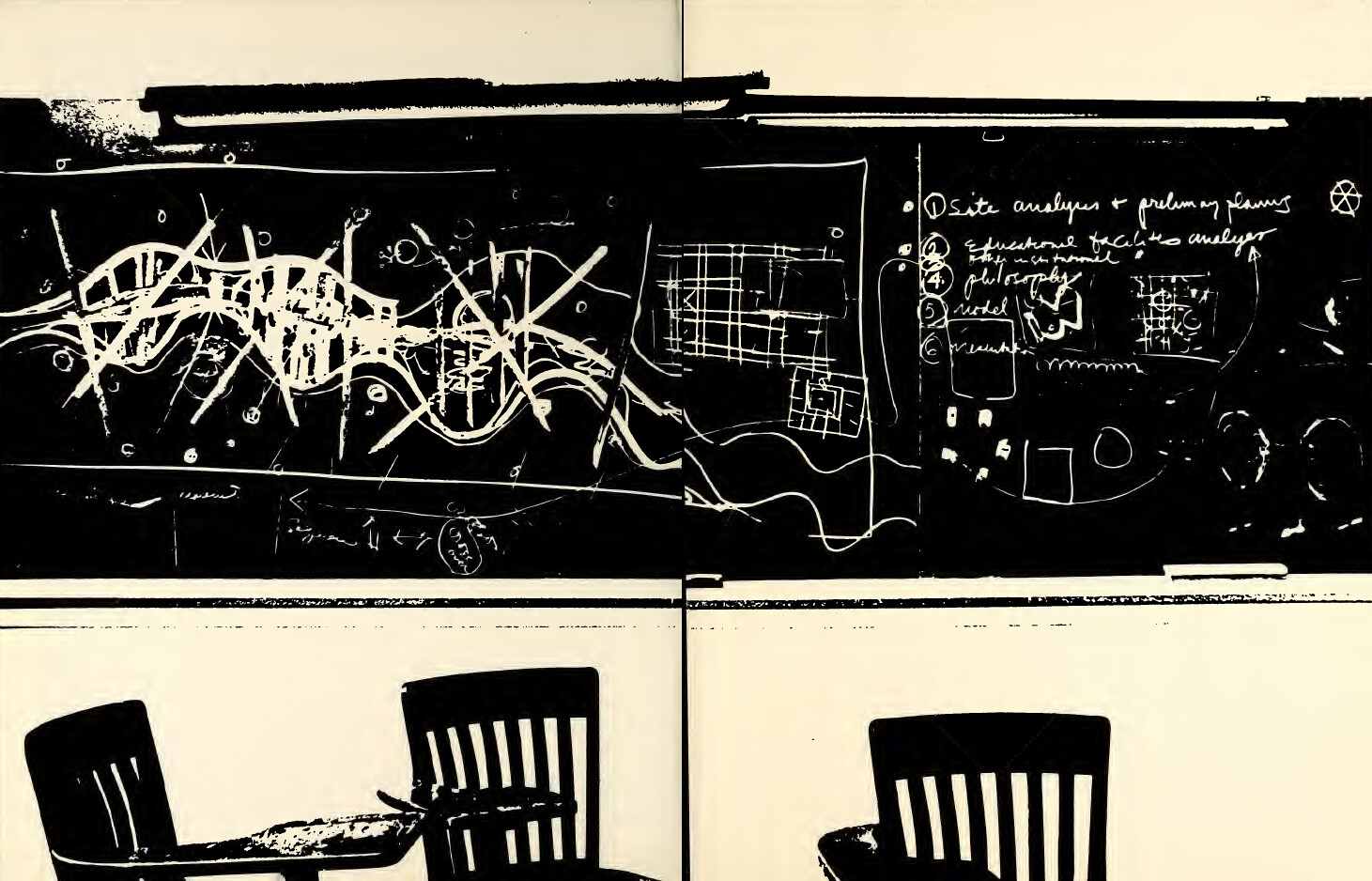

In line with such gestures of radical breaks with notions and structures of education, both magazines featured articles on the 1967 Rice Design Fete, a twelve-day-long workshop or “charrette” organized at the School of Architecture at Rice University in Houston, Texas.5 The first three previous iterations of the Design Fete had been devoted to community colleges, fall-out shelters and mental health centers. The fourth, 1967 edition it focused on “New Schools for New Towns.” The outcomes of this particular event are exemplary of a somewhat split consciousness: of self-proclaimed progressive design and educational endeavors that address the demands of social change, while at the same time disavow the political and social conflicts dominating the discussion in that period.

The event was co-sponsored by the Educational Facilities Laboratories, a New York-based consultancy agency on school building and educational economies funded by the Ford Foundation and long-time proponent of modular-prefab open plan architecture and the SCSD (School Construction Systems Development) system of flexible construction.6 The School of Architecture at Rice, headed by William Cannady, invited Charles Colbert, Niklaus Morgenthaler, Cedric Price, Robert Venturi, and Thomas Vreeland, as well as Paul Kennon, a professor at Rice, to team up with students from various universities joining the charrette to develop a project on the basis of different programs drawn up for the workshop by professional educators for new towns and their education systems.

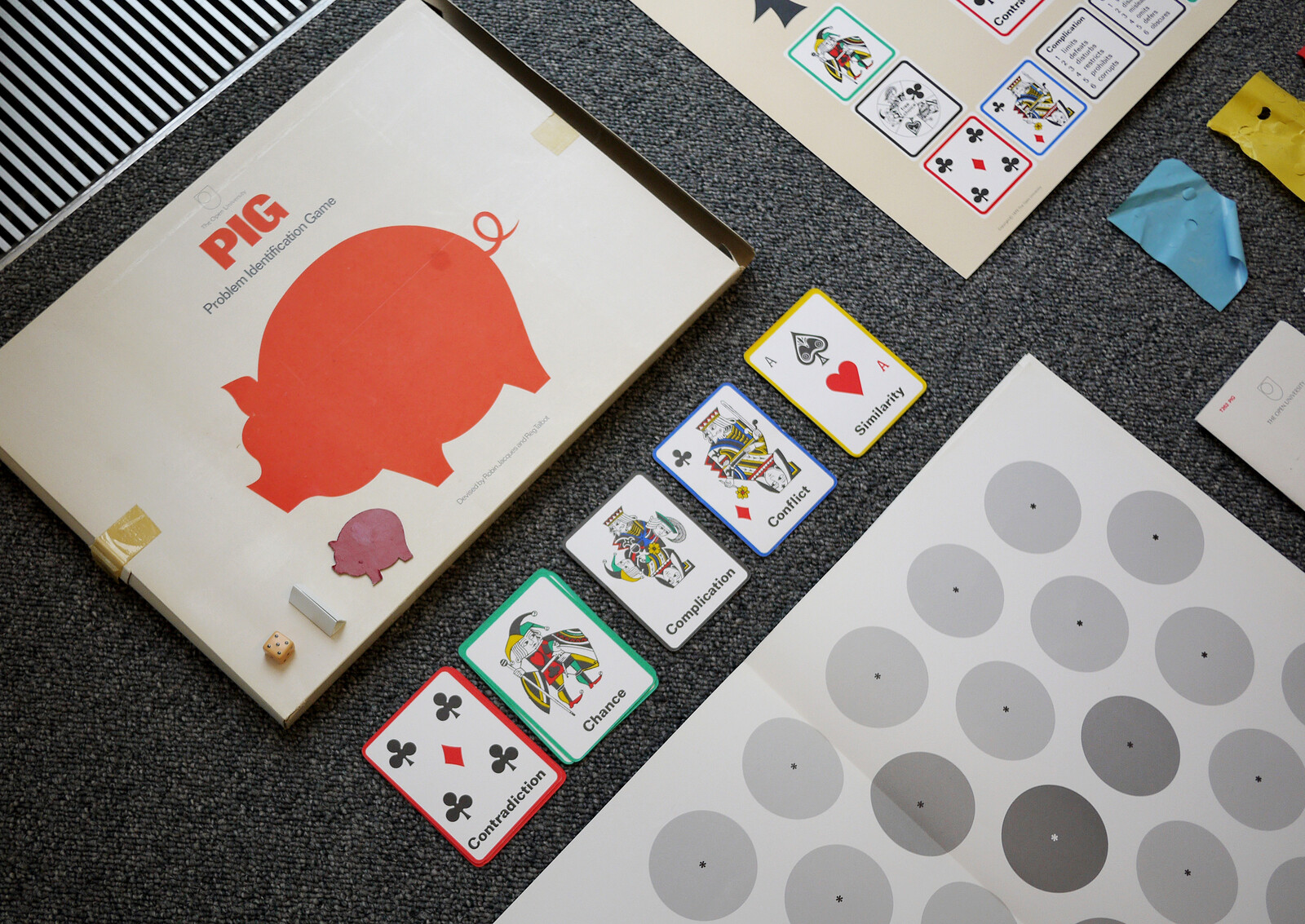

The programmatic brief of the Design Fete as a whole was drafted by Albert Canfield and John Tirrell, two educational consultants who had recently been employed by the Oakland Community College near Detroit.7 Canfield and Tirrell were extensively cited in Progressive Architecture and published their article “Goodbye to the Classroom” in the May 1968 Architectural Design issue. They advocated the technologically enhanced programming of small learning steps, the constancy of learning “as a continuing element in life.” They also argued for the “maximum utilization of all community facilities” as well as of “home study through portable packages,” thus “spreading communication among the community, so that it becomes an integral part of community living and the personal growth of the citizen.”8

In their AD article, Canfield and Tirrell were convinced that due to an increasing “effectiveness of self-instructional materials,” the need for teachers and tutors will decrease.9 Moreover, they proposed a “node for cultural/recreational activities in each of the neighborhoods” as well as “in industrial, business and commercial establishments.” For them, education was on the way from the school building and moving into the domestic sphere, the workplace, and new leisure architectures: “cultural/recreation centers will enhance and combine many of the cultural/educational/recreation activities formerly associated with separate institutions, such as the sports ground, art gallery, library, museum, elementary and secondary schools, university and factory.”10

These attempts to think differently about education sought to overcome its institutional paralysis, the dependence on spatial conditions such as the schoolhouse, and become more geographically dispersed and temporally extended. However, Canfield and Tirrell’s proposals remained within a planner’s mindset. And while they were ingrained by a technological optimism that may have been critical of the established forms and designs of schooling, they happily went along with larger economic and urban trends.

As for the selecting the educational requirements of “new towns” as its theme, the booklet published about the Rice Design Fete claims : “A new town presents an unmatched opportunity to explore new educational approaches and new ways of housing education without the constraints of continuity.”11 The blank slate approach of unfettered planning and design in brand new urban environments was intended to engender transfers into existing cities. The program had no strings attached, and thus aimed to bolster the creative energy of the participants.

Among the leading assumptions of the Design Fete was the increasing influence of technology on the learning experience, or the issue of instructional media and electronic teaching assistance. Other concerns were the necessity to “involve” (or “intermix”) the educational realm and the community, and last but not least, the importance of mobility in contemporary urban reality, or in other words, the need to find ways of making the time spent in trains and automobiles educational.

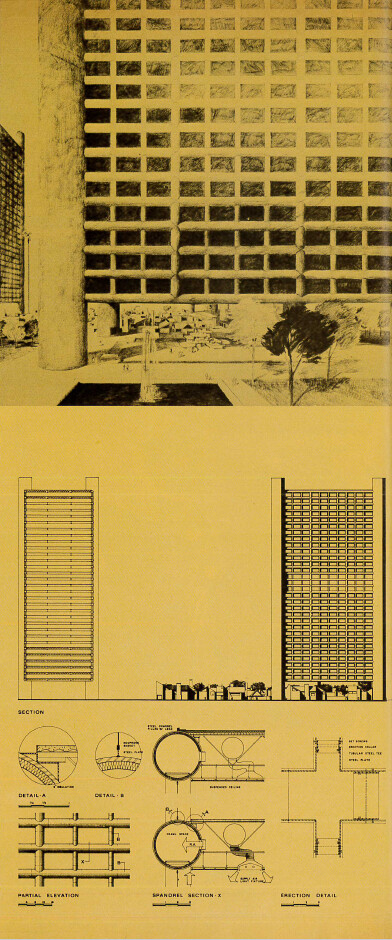

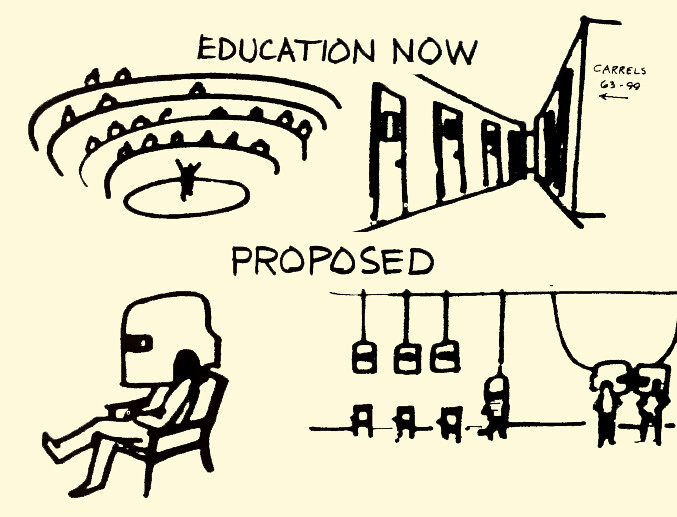

Visualization of the proposal by the group led by Charles Colbert. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

Elevations and sections of the proposal by the group led by Charles Colbert. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

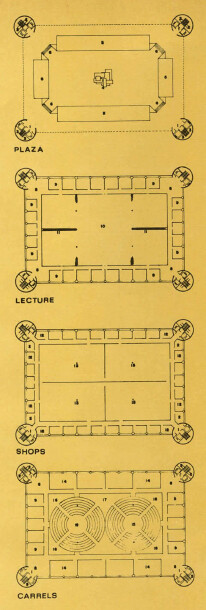

Typical plans of the proposal by the group led by Charles Colbert. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

Individualized education diagram, from the proposal by the group led by Charles Colbert. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967)

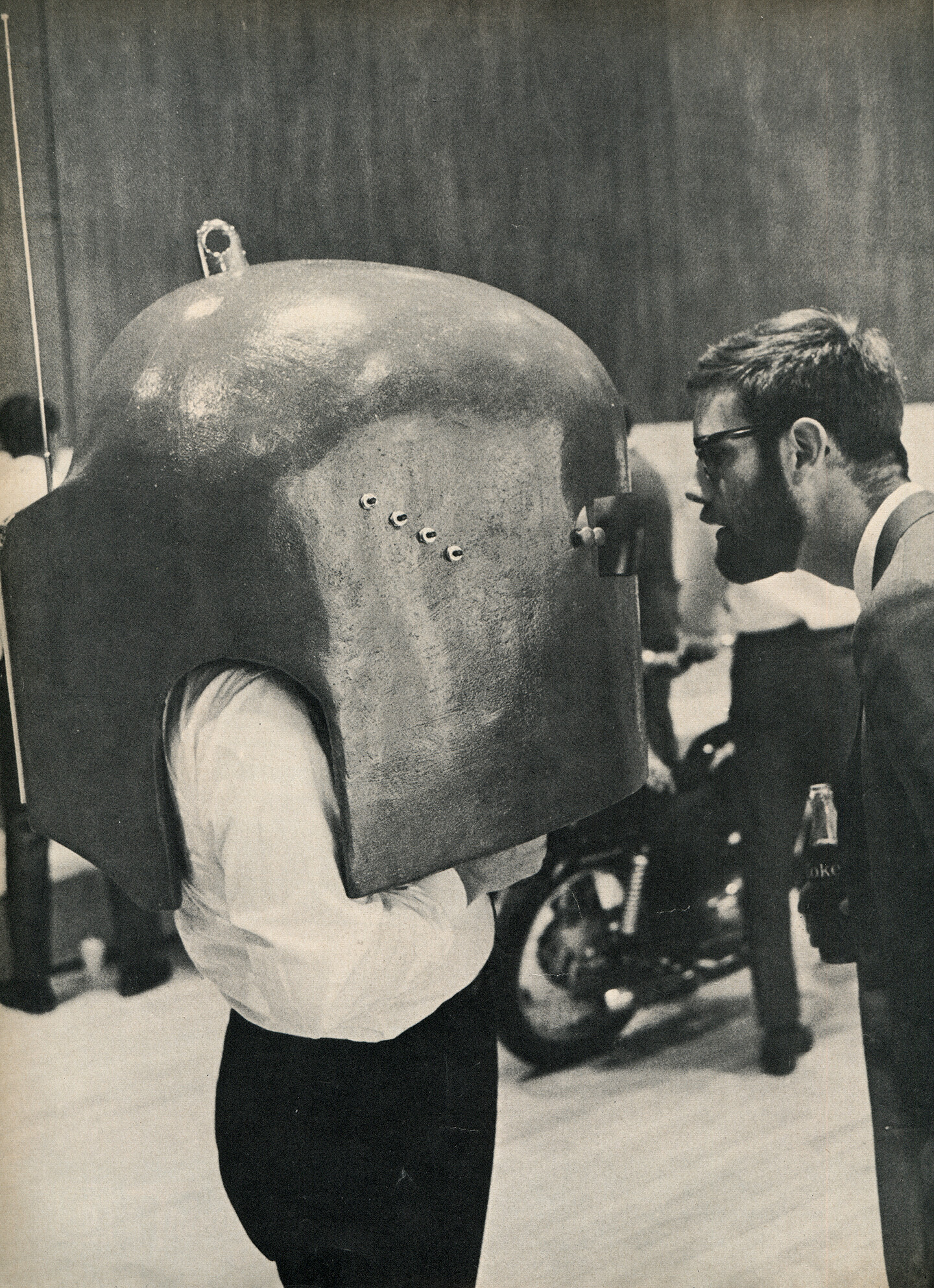

Shoulder carrel prototype, from the proposal by the group led by Charles Colbert. Source: Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

Visualization of the proposal by the group led by Charles Colbert. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

High-Rise Schools

Unsurprisingly, the results of each of the working groups happened to be quite different. Charles Colbert, an architect from New Orleans, and his group proposed educational towers constructed of steel pipe, for the envisioned new town would be developed by a steel company in relation to a new steel mill about thirty miles from Houston and was thought to evolve into a self-contained 150,000-resident satellite city. The “Towers’ school facilities would be available 24 hrs a day, serving students at high-school level and above, including adult education.”12

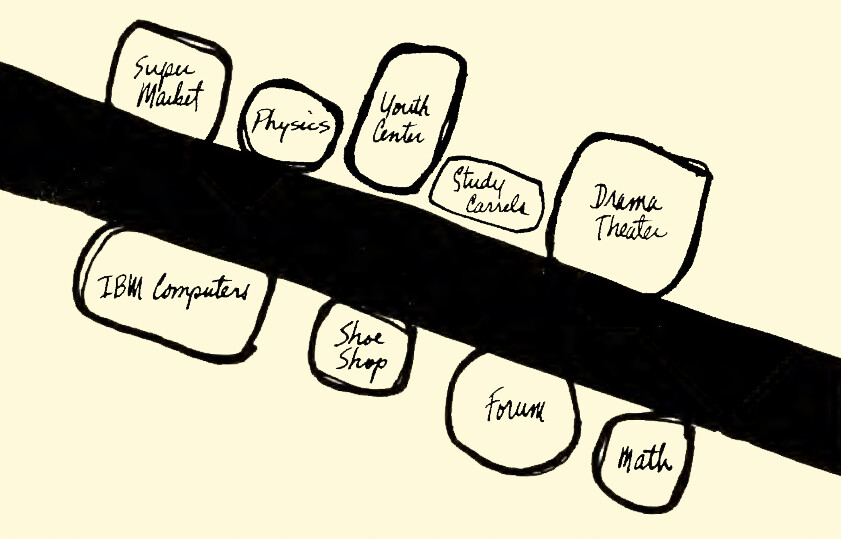

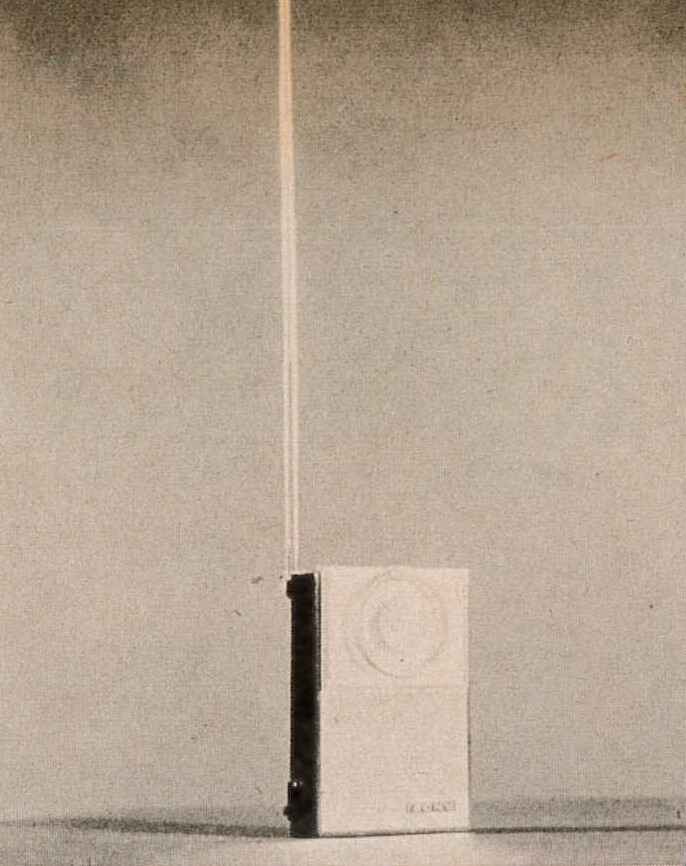

“Plans show the proposed school facilities; the floors above these would house corporate offices.” Although Canfield and Tirrell, the two educational consultants in charge of the program, were advocating the collapse of boundaries between institutions such as museums, libraries, parks, and the educational activity of the community, Colbert’s educational towers were considered to be bring corporate offices and schools too closely together. What’s more, even though the concentration of high school-level education in the community center seemed to respond to Canfield and Tirrell’s notion of the “community node,” it also wildly contradicted the ideas of decentralized, dispersed education. The Colbert group addressed this in almost satirical fashion, with its prototype of a “shoulder carrel”: a super-individualized learning device incorporating instructional media of all kinds, from television and tapes to computer connection, two-way radio, telephone, slide projector, and screen.

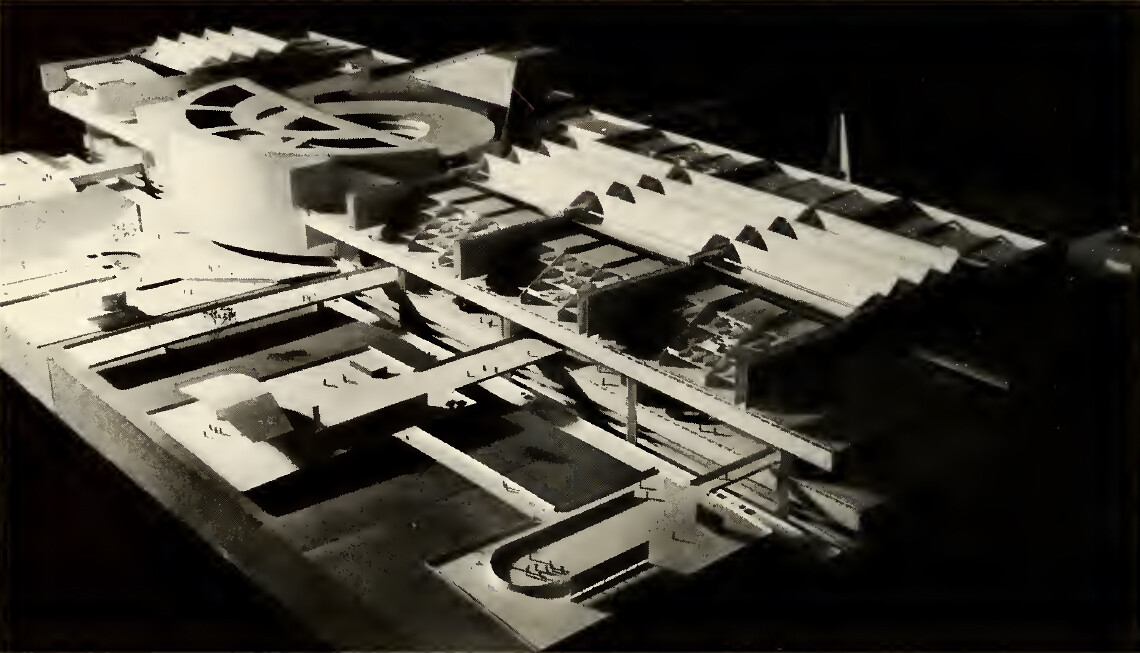

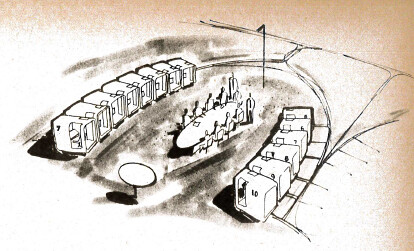

Model of the proposal by the group led by Paul Colbert. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

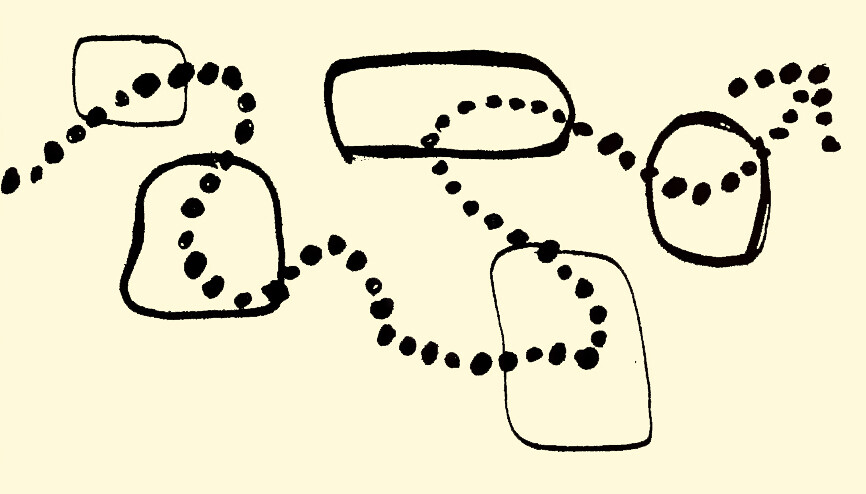

Diagram of “movement through activities instead of past them,” from the proposal by the group led by Paul Colbert. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Diagram of the “Grand Intermix,” from the proposal by the group led by Paul Colbert. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

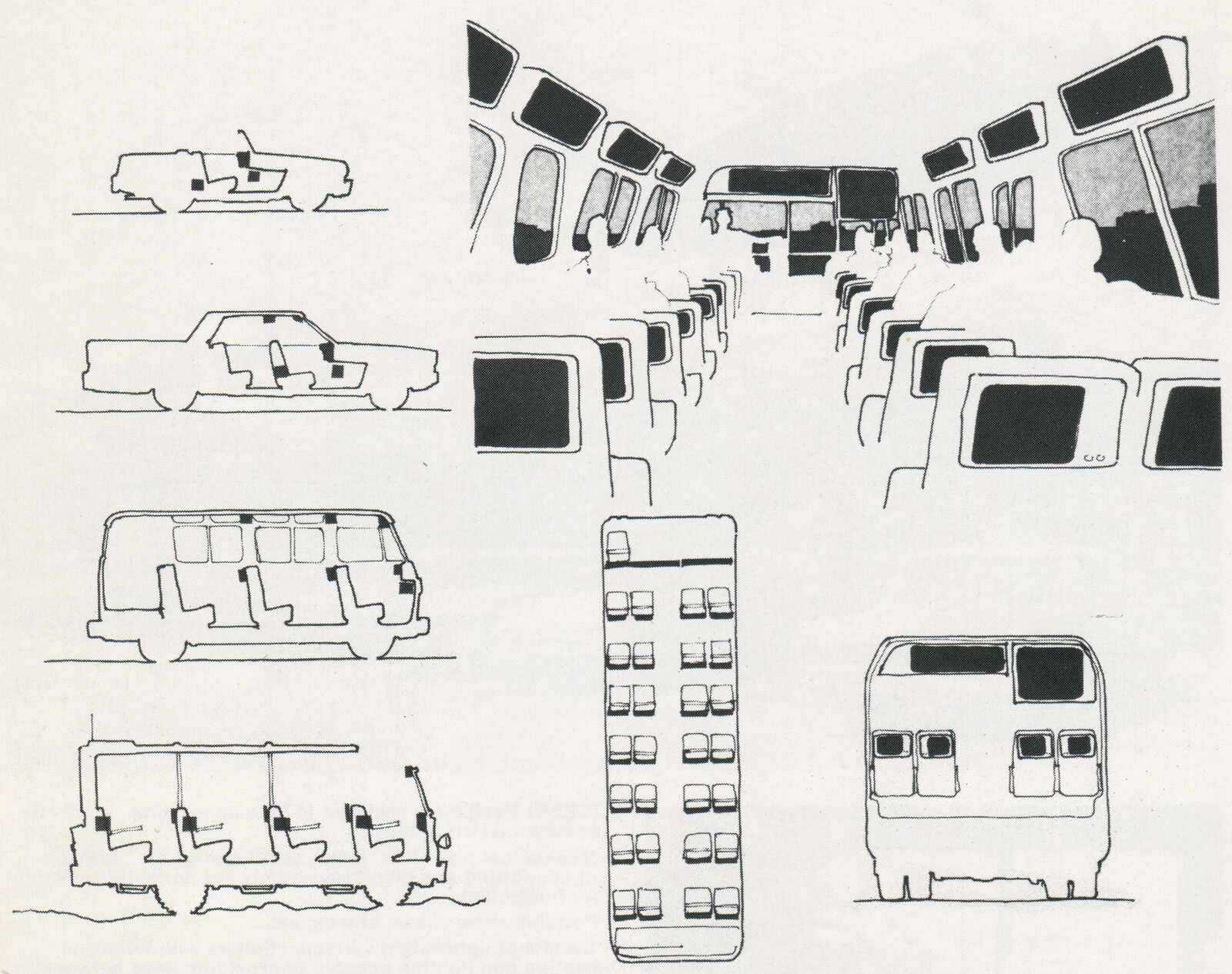

Sketch of the computerized carrel cars, from the proposal by the group led by Paul Colbert. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

Model of the proposal by the group led by Paul Colbert. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

The individualized space of study has always been a particular task for designers of library and workplace furniture. Around 1967, it was already possible to conceive of a mobile learner interface with limitless access to audiovisual and textual archives, a sturdy precursor of what by has become everyone’s handheld wireless device. Yet freeing the individual from any larger architectural structure and entitling them to become this architecture resembles the nightmarish opposite of any community-centered notion of involvement via education.

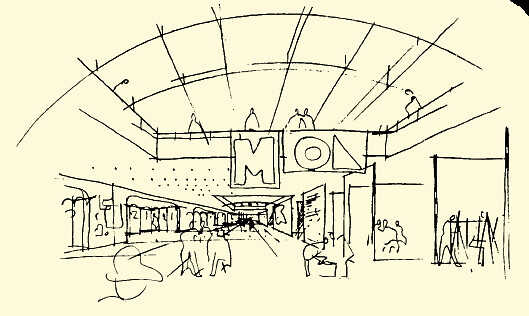

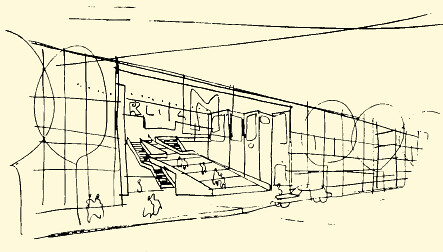

Houston-based architect Paul Kennon came up with an educational plan structurally similar to Colbert’s proposal, yet different in its architectural references. Rather than designing towers, Kennon was drawing on the horizontal model of the suburban shopping mall. Responding to a brief by Dorothy M. Knoell, a programmer at the State University of New York and author of the 1966 book Toward Educational Opportunity for All, for a new town thirty miles east of Los Angeles, Kennon’s Educational Concourse was a university campus based on a notion of the university as a “generator of community services.”13

The multifunctional megastructure of the new town is designed as an urban strip with the educational hub as a kind of central machinery. “Computerized Carrel Cars” allow for speedy commuting for constant learners. “The carrel car is in reality a flexible space,” the commentary in Progressive Architecture elaborates, “[a space] that can be attached to homes as study rooms, serve as a mobile study, docked at the school or drawn up in a protective semicircle like covered wagons to ward off the arrows of ignorance.”14 In diagrams, the Kennon group visualized the “intermix” and the type of “movement” that would be an ongoing and total engagement with this educational-consumerist environment.

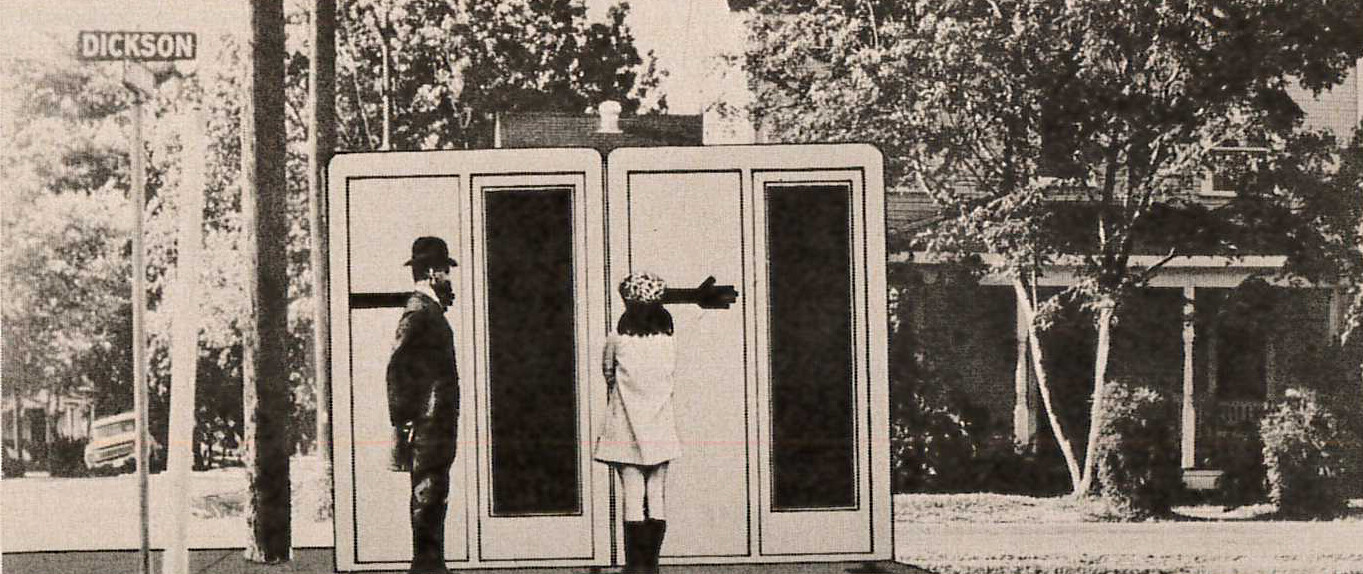

Mobile teaching unit, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Individual hand-carried unit, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

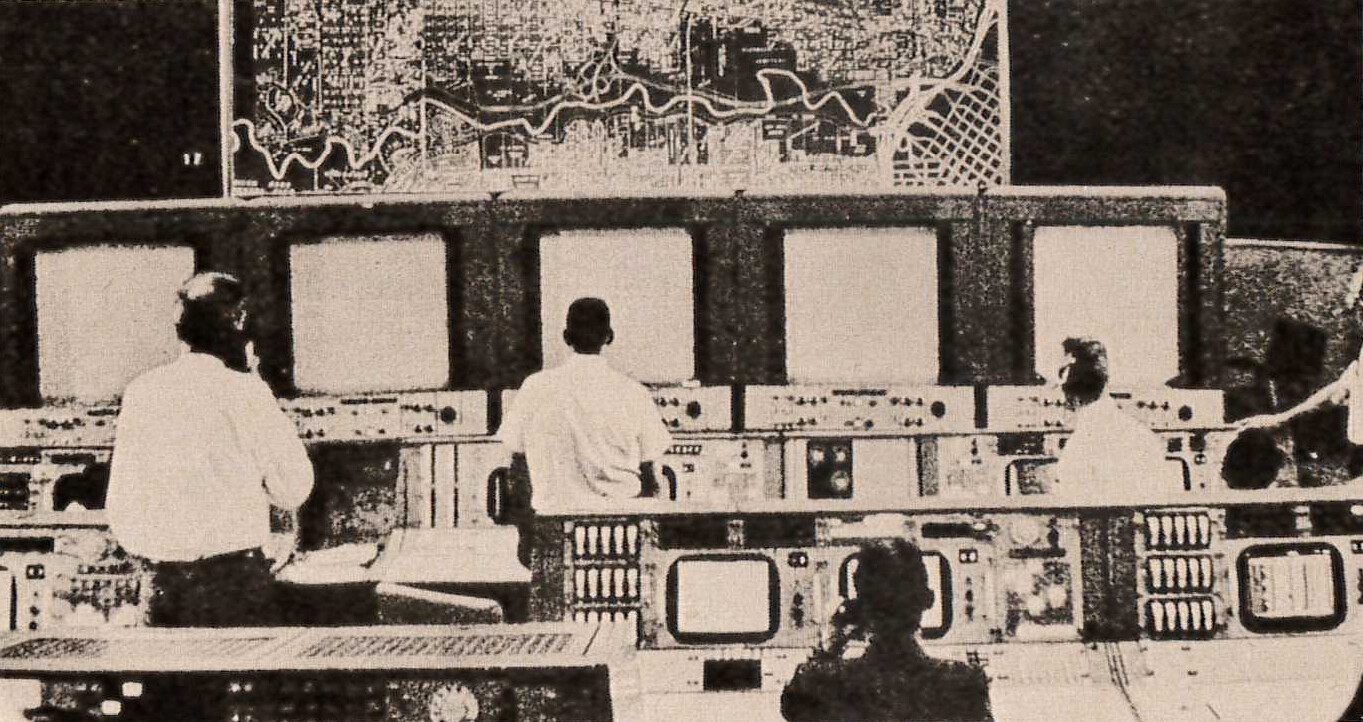

Central control, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Child care center, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Individual study unit, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Drive-in study unit, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Mobile teaching unit, from the proposal by the group led by Thomas Vreeland. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

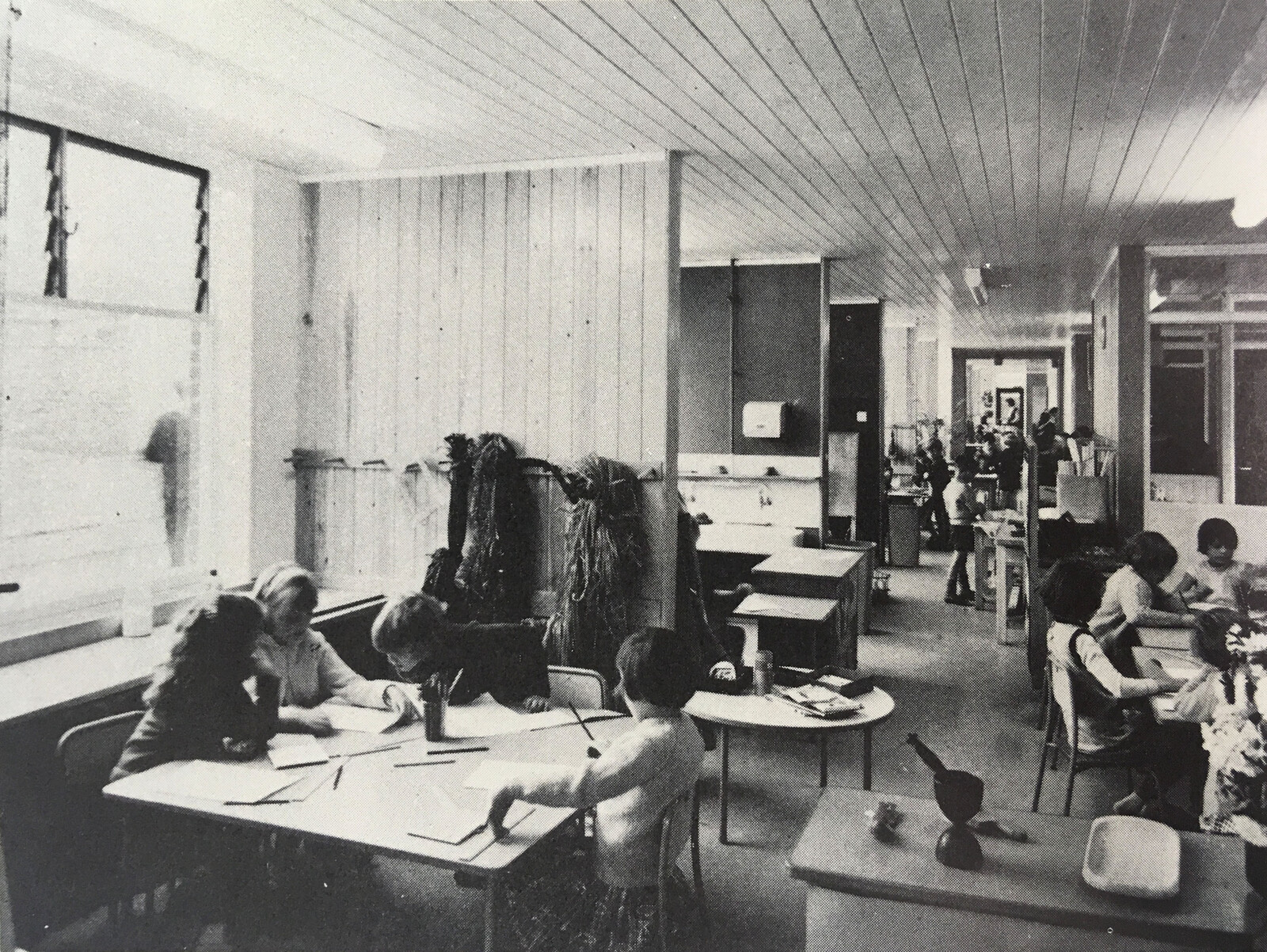

Dispersed Education

The group of Thomas Vreeland, who founded the CASE group in 1964 together with Peter Eisenman, Colin Rowe and others, was advised by educators Cyril Sargent and Judith Ruchkin to come up with a proposal for the subtle, minimally invasive makeover of an existing, multi-ethnic, but deteriorating community adjacent to downtown Houston. The program called for an “experimental approach” to manipulate urban space but refrain from razing the neighborhood’s buildings or other ways of creating a blank slate from which to build anew. Starting from the assumption that all participants are “learners, with no age barriers” who tend to be “dispersed,” the rehabilitation of the community in decay was designed to be facilitated by the “restructuring of learners’ time,” attention to “varied learning rhythms,” and the potential displacement of learning facilities, even “overnight,” if necessary.15 The project was strongly informed by the educators’ ideas about a “linear community school” that would be equipped with cybernetic devices to retrieve and feedback on data from an electronic database. The purpose of such a “linear” school would be “to foster development of personal qualities of independence, creativity, imagination as well as sympathy, reliability, and responsibility. In the community school the learner … becomes free to search, to investigate.”

Vreeland and his group abstained from the kind of architectural design and urban planning approach that Kennon and Colbert had opted for, although they share a certain technological optimism. Vreeland rather went for micro-interventions into the existing environment of the neighborhood and for an inversion of the spatiality of the traditional school model. A Volkswagen bus carries educational content and instructional technology to the “learners” in the city, rather than transporting the students to far away schools.

Through the image of the Volkswagen bus as mobile educational unit, Vreeland also inserted an, if implicit, commentary on the heated debates around the pros and cons of school busing in relation to segregation. Among the measures proposed at the time to desegregate the system were large, centralized, and integrated school campus structures, so called “education parks.” Such school centers were to be linked with more distant communities mostly by busing. Reminiscent of key events in the civil rights movement of the 1950s, the controversy around busing garnered considerable attention in the 1960s and 1970s. In the process, the image of the bus and of students being transported from inner cities to new suburban education hubs to benefit from integrated schools developed into an icon of educational politics across racial and political divides.16

For Vreeland, the “portability” of educational hardware was a key methodology to disseminate the school into the community and facilitate educational activity from the point of view of the “learners,” their interests and needs. But it wasn’t only about turning around common ideas of the student and of schooling, of doing away with compulsory learning, grading, and other forms of educational control. Vreeland’s project aimed for urban regeneration rather than renewal. Their network approach was meant to be “capable of functioning as a major regenerative force in the life of the community, a force capable of effectuating gradual social, economic, and cultural changes.” At the same time, their project was expected to be productive in scientific terms. Designed as “all-pervasive,” the network was “to touch the community unobtrusively at as many points as possible… It works by feeding information about the community for scientific analysis. It forms a sensitive communications network.”17

A typology or taxonomy of educational facilities became a tool to visualize and systematize the project’s logic and economy, from the individual hand-carried unit (a battery-powered, transistorized radio receiver) to portable conference rooms, mobile teaching units such as the Volkswagen bus, prefab learning centers of different size and functionality, and the “central computer bank, monitoring and programming center.” The miniaturizing and modularizing of education by way of technological devices, prefab building systems, portability and mobility of spatial units, and centralized databases was a telling attempt at imagining the new town as an essentially nomadic, DIY trailer park environment, deliberately neglecting the symbolism of institutional representation. Immersed in self-organized, autonomous, interest-driven educational activity, this envisioned community is a piece of systems aesthetics, if not a fantasy of alternative cyberneticism. Although (or because) Vreeland’s project was the only one in the Fete about a multi-ethnic part of the city, it still transcended all troubling divides of race, class, and gender, generalizing the identity of the “learner” about everything else.

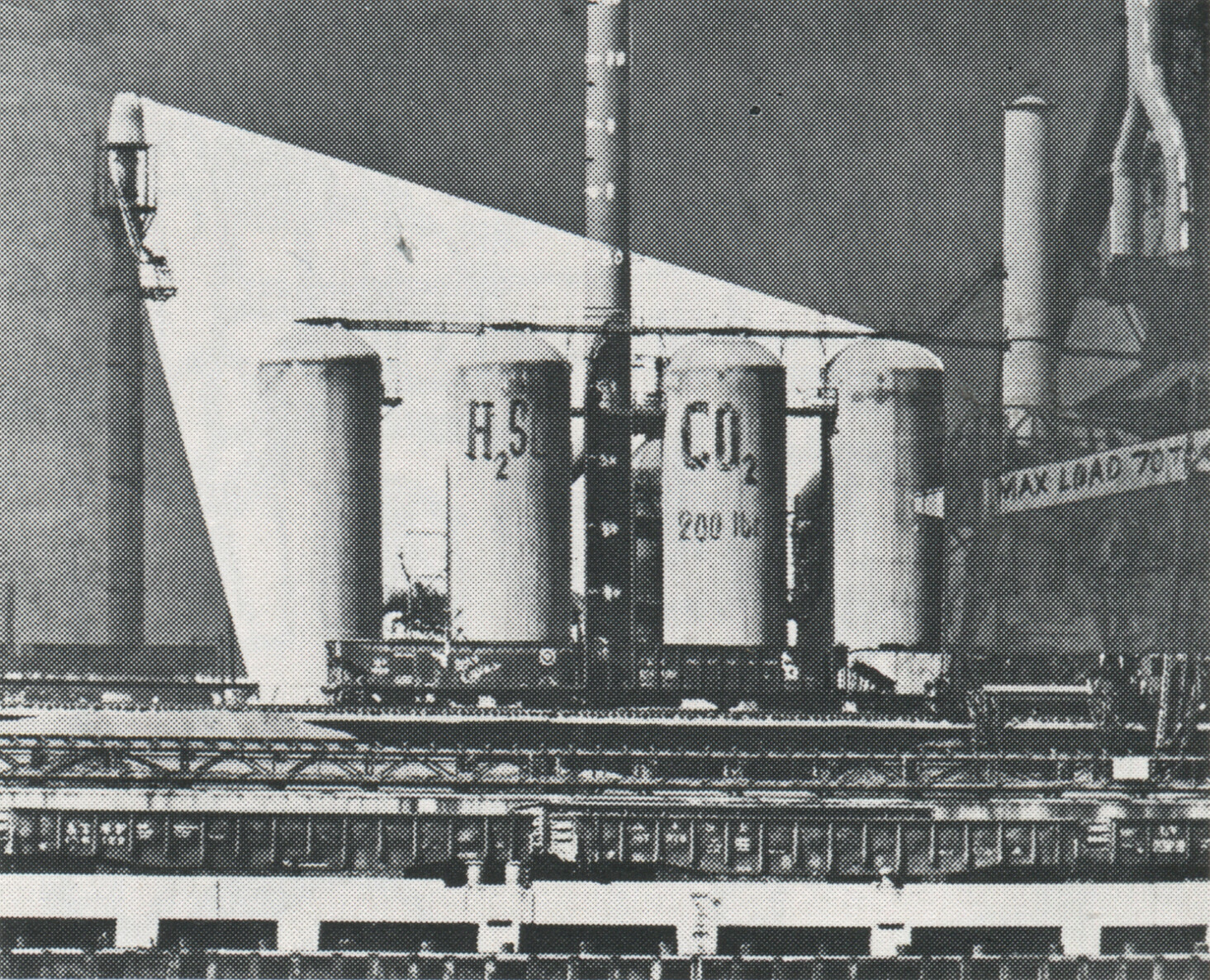

Kit of parts, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

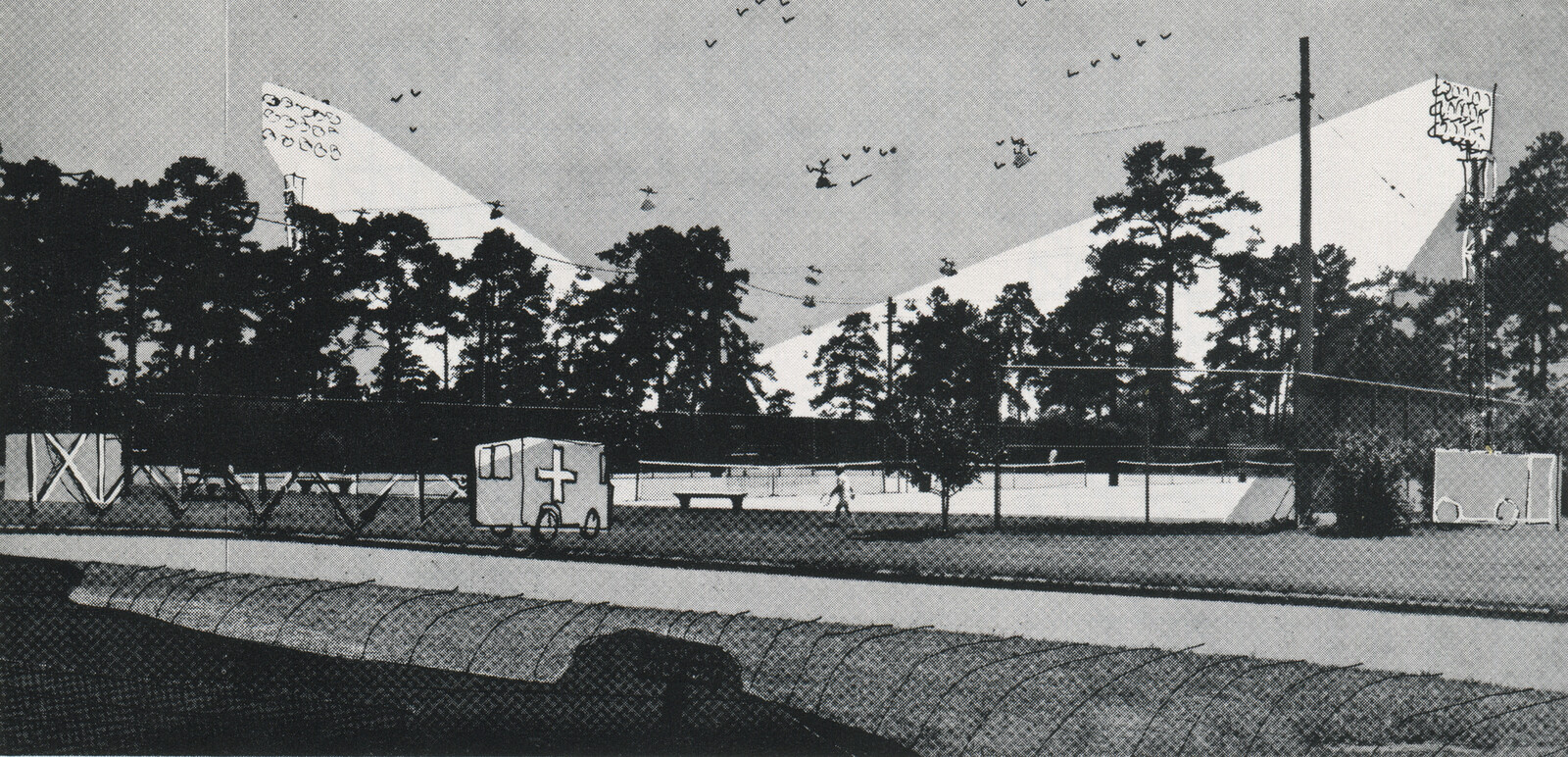

(OAS) Open-Air Servicing, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

(OAS) Open-Air Servicing, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

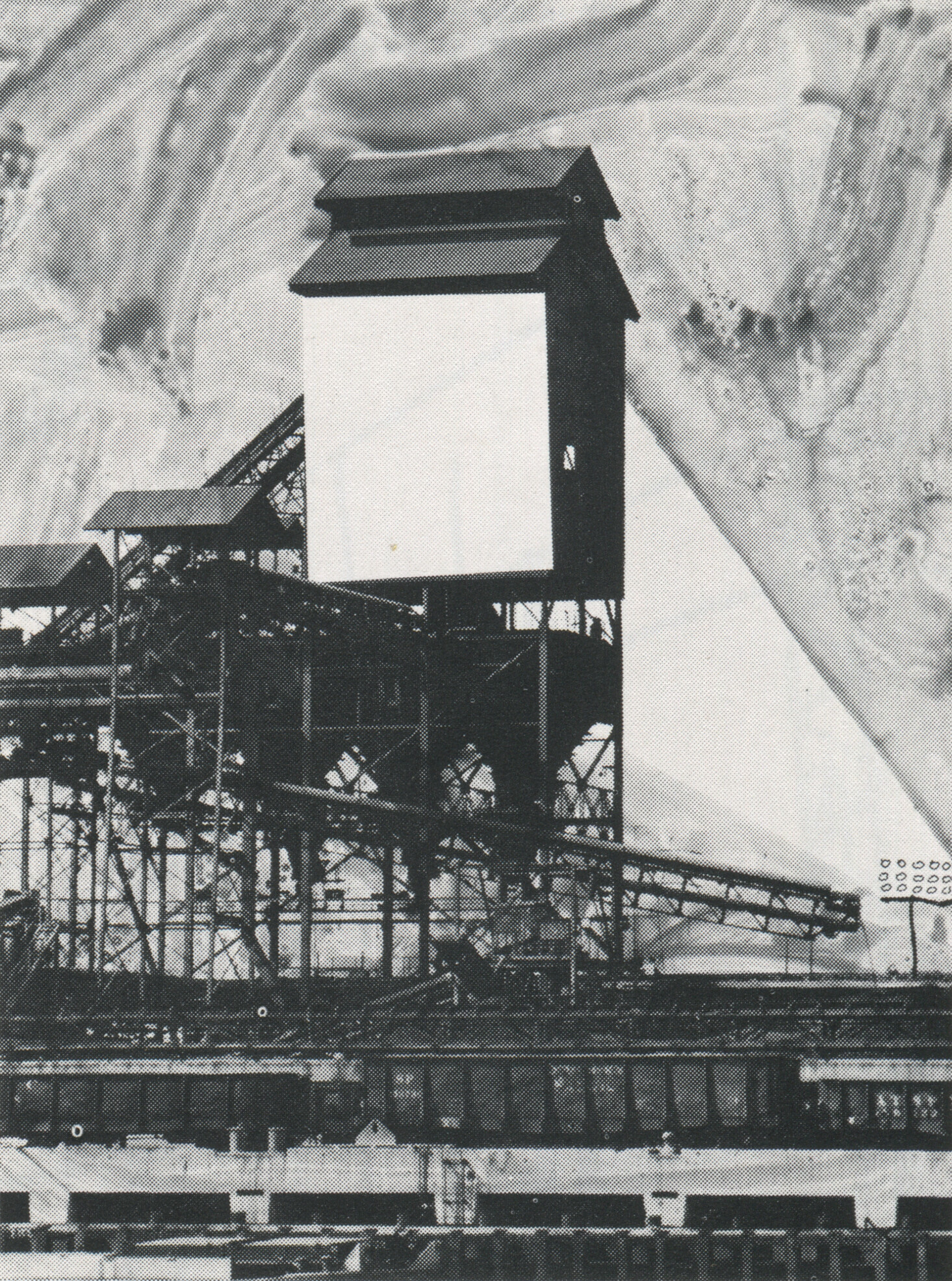

(IESC) Industrial/Educational Showcase, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

(IESC) Industrial/Educational Showcase, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

(RTS) Rapid Transit Servicing, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

(CESC) Commercial/Educational Showcase, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

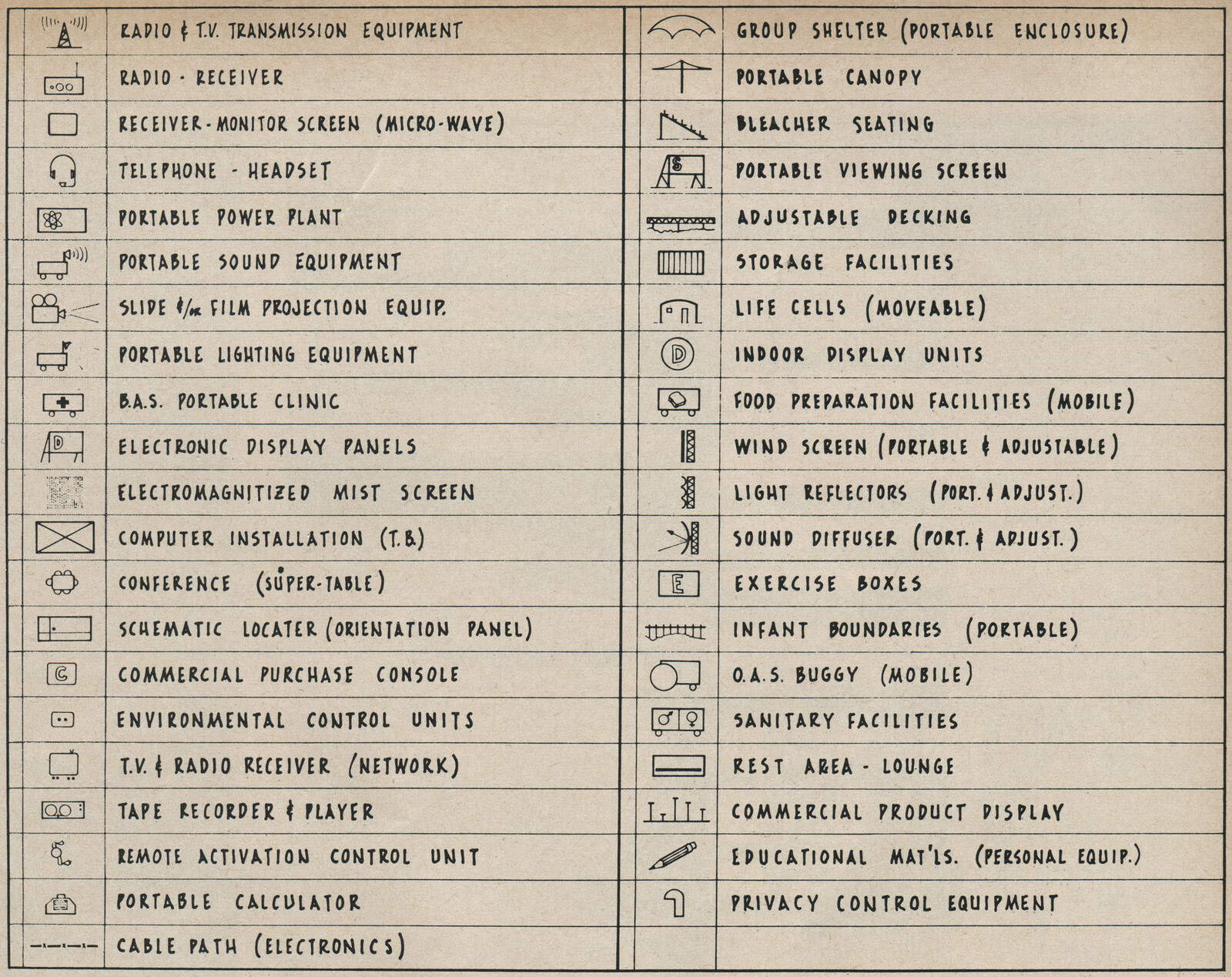

Kit of parts, from the proposal by the group led by Cedric Price. Source: “New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968).

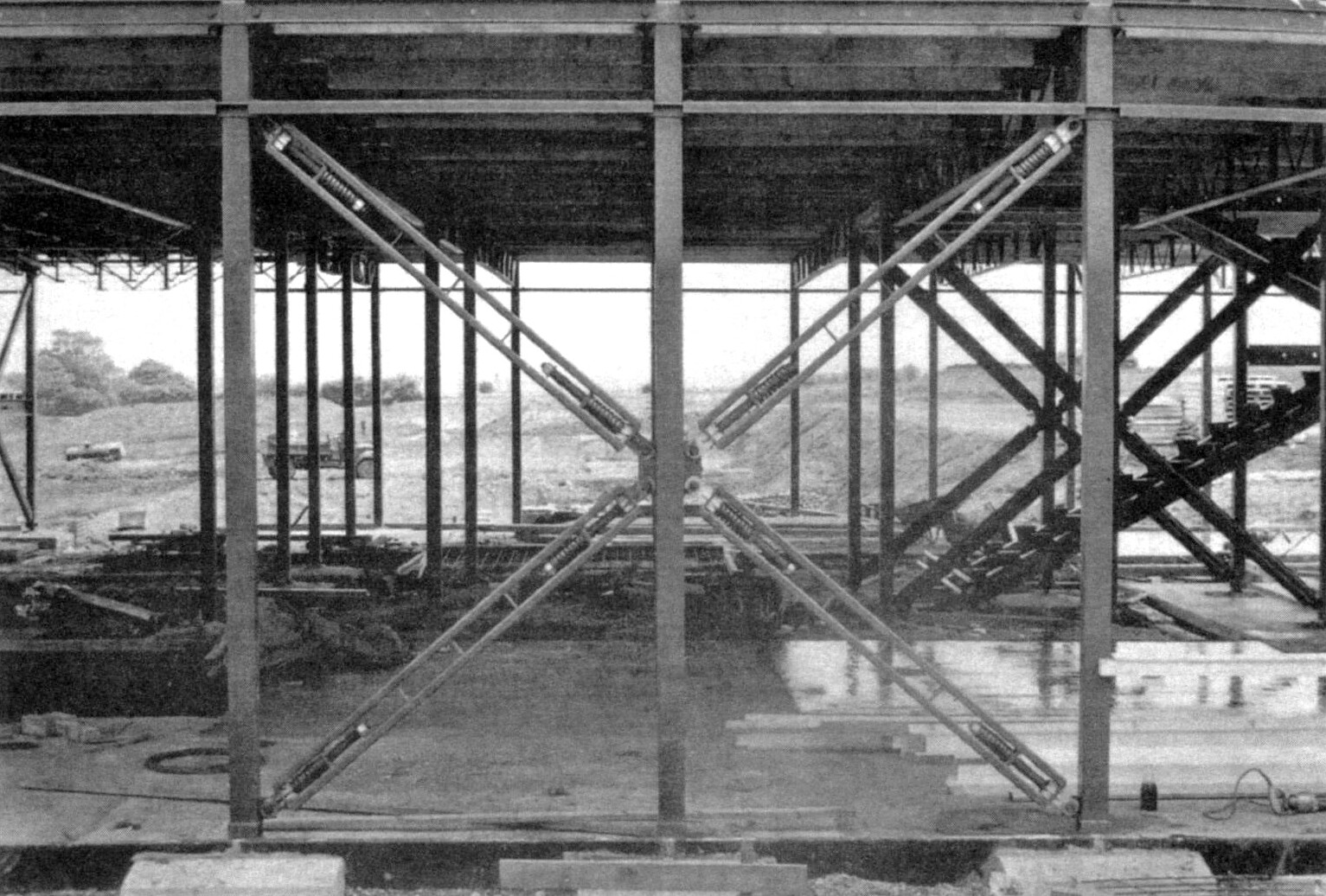

Total Learning Environment

Cedric Price had been invited to Houston with the knowledge of his outstanding portfolio of peculiar projects of designs for new types of educational environments. Potteries Thinkbelt, for instance, was a large scale project to convert an existing industrial site and its infrastructure in North Staffordshire into a vast educational network for 20,000 students, who he imagined to be hired as wage earners rather than paying tuition fees or receiving grants. Price brought some elements from Potteries Thinkbelt to the Rice Design Fete, where he developed them further. What Vreeland has called the “components” of the educational experience, Price named “parts.” For the project that he proposed on the grounds of John Tirrell and Albert Canfield’s program, Price also came up with a list or taxonomy, a “kit of parts.”

Using acronyms and little symbols, the “kit of parts” contained all sorts of technological devices from “telephone headsets,” slide and film projectors, and assorted items of outdoor and indoor furniture and architecture, including “electronic display panels,” a “portable canopy,” and “bleacher seating.” In his urban-scale taxonomy, Price listed “(TB) The Town Brain: Central production and servicing for Educational Facilities (EF),” “(IESC) Industrial/Educational Showcase: Displays to explain industry to the public,” “(AL) Auto Link: Education facilities … made available to private cars with radio, two-way telephones, and charts,” “(RTS) Rapid Transit Servicing: Education facilities in buses, trains, etc., including informational panels,” and more.

His project for a “Total Learning Environment with a Kit of Parts” reveled in the potential of manipulating and modifying the urban environment to generate educational situations and place knowledge hubs (or “nodes”) at the most unexpected sites. A “part” of the educational landscape could thus be a wrecked car suspended upside down below an elevated expressway, or a boat mounted on the roof of a strip mall. Public parks were to be turned into educational arenas, stressing the equivalence of sport event and schooling; industrial or infrastructural buildings repurposed as screens on which industry would educate the public about what it does while hidden from view; car interiors or bus seats transformed into multi-media learning carrels.

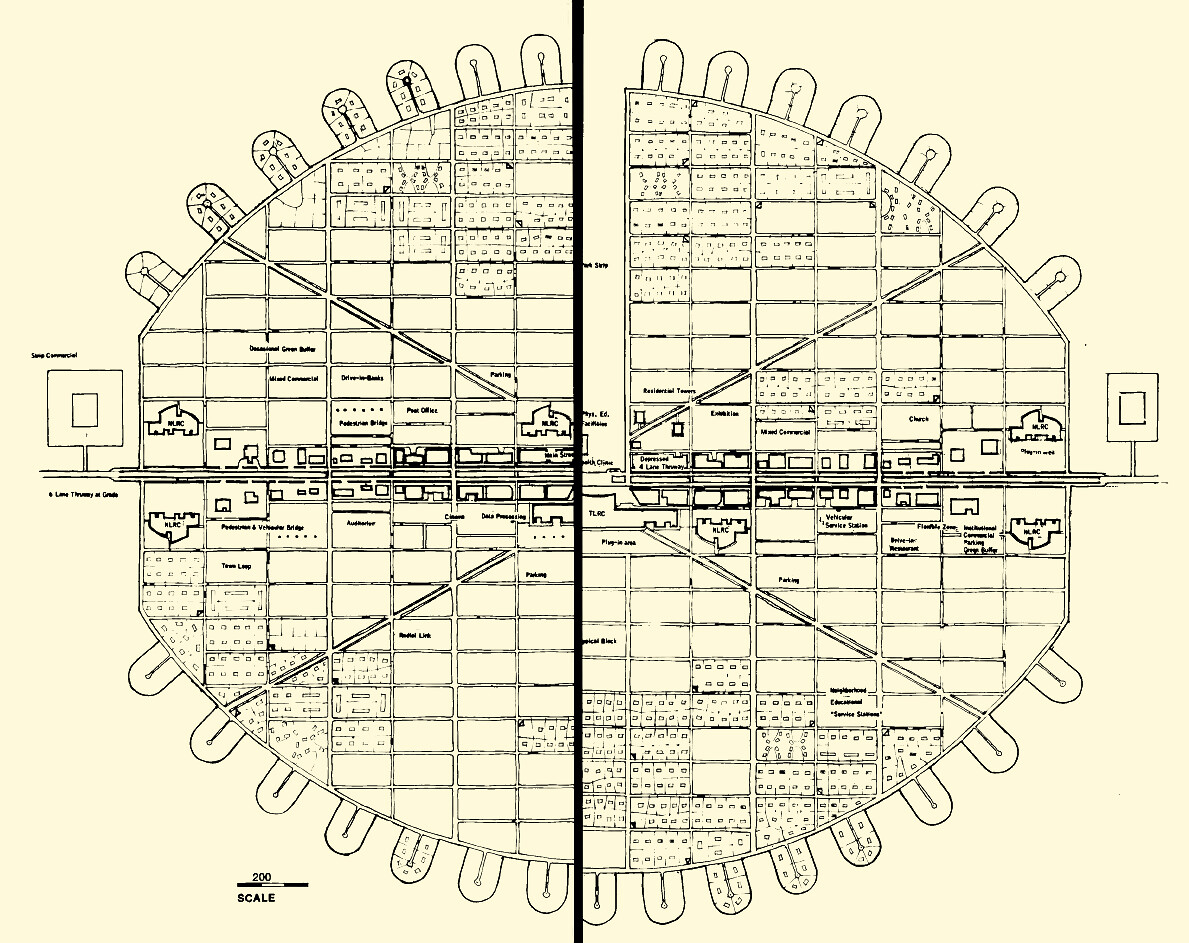

The new town selected for this project was a residential satellite city of medium density thirty miles southwest of Chicago, “located on a major radial freeway with a highly educated population of 200,000”—a population “predominantly professional, semiprofessional, and skilled.”18 In the article Price published in the May 1968 issue of Architectural Design, the Rice project and its brief had been replaced, while elements of it remained. Renaming it “Atom,” he abandoned the idea of the plannable “finite town,” and declared the concept of settlement built for long-term usage obsolete. Instead, he was convinced of the inevitable fragmentation of infrastructural “servicing” and “increased individual mobility and personal independence,” and sought to explore its effects on how urban societies are organized.

Price didn’t entirely refrain from designing new architectural spaces, as is demonstrated by the LC or “Life Conditioner”: a simple, box-like structure to contain maximally flexible learning units and placed alongside the freeway. Price explains the typological background as: “Two forms, box and tent.” “Box contains intensive teaching learning facilities and controlled medium-sized volumes food drink and CESC [Commercial/Educational Show-case]. Tent—workshops, laboratories, experimental buildings, etc. Boxes likely to be less frequent in Phase III because of growth of HSS [Home Study Station], while tents likely to increase.”19

These presumably cheap, makeshift, highly flexible, and ephemeral structures were meant to constantly be assembled and disassembled and discarded once they no longer fit into an evolved educational way of thinking. For Price, the “built environment” was rapidly becoming less and less “socially relevant,” as it is based on ideas of economic growth unaware of the entropic nature of contemporary societies of communication. “Fortunately,” Price maintained, “it is unlikely that education, now entering a period of mammoth expansion in scope and content, will wait around for such stultifying recognition.”

The “Educational Facilities” (EF) diagrammed in a 1967 drawing, however, show how much organization and geometric order seemed necessary to form the fragmented and de-differentiated urbanscape of learning. It also provided the kind of intelligibility or readability aspired by the community of planners and educators.

For Price, teaming up with progressive educators such as Canfield and Tirrell had been following Price’s prior work from a distance and were about to adapt his notion of “thinkbelt” for their own planning of community colleges in the Detroit area. Their collaboration in the Fete proved inspiring. “[The] value of this programme [referring to Canfield and Tirrell’s conceptual launchpad] at such a time,” Price wrote,

is that it has enabled me to show that the built environment together with its integral artifactual kit of parts can help to increase the rate of fruitful fragmentation of educational servicing… However the acceptance of educational servicing as continuous, essential feed to the total lifespan, does demand an acceptance of the fact that education together with other essential services must be made available in means and methods comparable with other forms of invisible servicing.20

This rhetoric of educational spaces and technologies becoming invisible or indistinguishable ran against any notion of architecture as built and a potentially monumental statement. Rather, Price’s somewhat passive-aggressive de-centering and devaluating of more traditional ideas of shelter and brick and mortar containers privileges a decidedly environmental approach. His approach suggested a wholesale activation of everything towards a new educational functionality that already constitutes the urban infrastructure, from the micro to the macro level.

Like most of his colleagues, Price didn’t speak much about what exactly he thinks could be taught and learned in this fragmented, entropic, splintered environment saturated with educational offers and incentives. The curriculum, it could be argued, yields in the training of a different attitude, an attitude directed towards an arguably post-institutional reality of learning. But this reality remained as patterned, albeit non-differentiated of a life-world as the techno-spatial environment it presupposed.

Diagram of the proposal by the group led by Robert Venturi. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Proposal to use billboards for education by the group led by Robert Venturi. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Town plan of the proposal by the group led by Robert Venturi. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

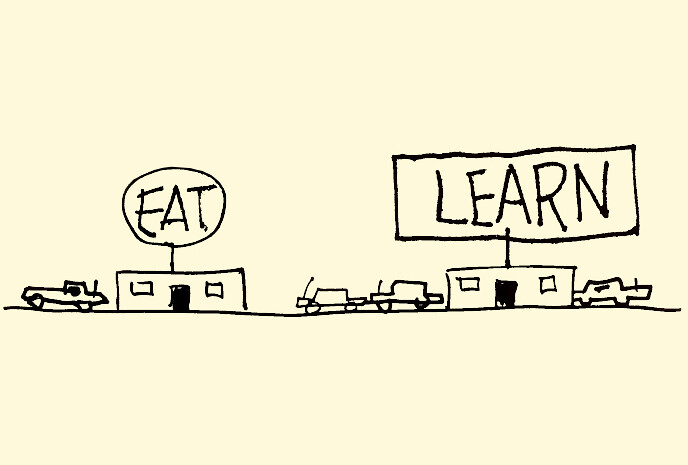

Sketch of learning centers within the Educational-Commercial Strip, from the proposal by the group led by Robert Venturi. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Sketch of learning centers within the Educational-Commercial Strip, from the proposal by the group led by Robert Venturi. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Diagram of the proposal by the group led by Robert Venturi. Source: New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston, TX: self-published, 1967).

Learning Strip

In many respects, interpreting the new town as a space of learning, understanding urban education as educationalizing the urban, and making the presence of the school in the expanded field of the city unavoidable anticipated the proverbial notion of “learning from.” A year before Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown, Steven Izenour, and their Yale students started research into the cityscape of Las Vegas in the fall of 1968, Venturi developed a project at the Design Fete that displayed a similar interest in the semiotics and semantics of the commercial street and the futility of “good design.”

Carol Lubin and Ronald W. Haase envisioned a self-contained 150,000-resident new town halfway between Washington DC and Baltimore for the Venturi group, and called for a “library-centered educational system.” Responding to the brief, the Venturi group equipped neighborhoods of 500 families with twenty-four-hour Learning Resource Centers, one for small children, one for young mothers, and another for retired persons. These center facilities “could be enlarged by the use of both mobile visiting units and closed-circuit television. Special plug-in areas for bookmobiles, artmobiles, scientific exhibitions, and healthmobiles to visit and service the neighborhood would be provided.”21 Besides the basic Learning Resource Centers, larger centers such as Town Learning Centers, Senior Learning Centers, and major City Learning Centers were to be distributed throughout the new town grid.

The Venturi group also proposed even smaller learning units in the form of “Service Stations.” The architecture of these and the Town Learning Centers were to be simple, skeletal, and placed on the “educational strip” so as to be reachable by car and bus. Fully in compliance with the main street model of the common American settlement and the suburban town modeled after it, Venturi conceived an “intermix” of educational, commercial, and mobility systems, with the educational strip as the generator of the new town. “A commercial educational strip arrangement for a new town provides a constantly diverting route for the pedestrian and the motorist. Rather than denying the existence of and the necessity for the freeway and the attendant jumble of buildings and automobiles, [the project] mingles education facilities directly with those for commerce—along a town-bisecting freeway—and creates a varied smorgasbord of attractions to compete for the attention of the pedestrian and motorist learner.”22

Educationalizing the Crisis

Further archival research is necessary to ascertain how the proposals from the “New Schools for New Towns” Rice Design Fete were received in the respective circles of planners, educators, and architects. However, already in 1967, blending education into the consumerist environment of the capitalist city, embracing the suspiciously commercial as well as the neo-vernacular of the pop age, and suspending any culturally inherited divisions between high and low, learning and working, education and consumerism in favor of a model of the citizen as constant, life-long learner could be seen as an enervating, even obnoxious stance by critics of the culture of capitalist order.

On the other hand, the scandalizing of traditional, and particularly Marxist modes of critique and criticality as performed by Venturi and others could be read as an early expression of post-modernist avant-gardism. It could also be read as a sign of the refusal to be aligned with more openly political movements and organizations, or only an academic, political, administrative and managerial class that was increasingly concerned with issues of racism, segregation, and integration.

In 1967 Alvin Toffler, a journalist about to assume celebrity status for the 1970 futurologist bestseller Future Shock (written together with his partner Heidi Toffler), edited a collection of talks that had been delivered in a 1966 conference titled “Schoolhouse in the City.” It focused on the perceived urban “crisis” which was caused by the continuing racializing of space, real estate speculation and the mega-business of renewal that has led to the deterioration and ghettoization of downtown and urban residential areas, and the production of the suburban sprawl for a white population deserting the city. In many respects, the programs and the results of the Rice Design Fete in 1967 were a reaction to the kind of discussion documented in this volume.

Throughout, the texts in Toffler’s anthology were driven by the alarming facts and statistics evidencing urban decay and ongoing segregation. The book tried hard to provide analysis as well as educational and design proposals to solve the crisis. The prominent black leader as Bayard Rustin, for instance, addressed the “’boxed-in’ feeling,” “the sense of no place to go, the lack of outlet” in the African-American “ghetto” communities, as well as the reasons “why schools have become a primary target of the ghetto activist.”23 “Unless there is a master plan to cover housing, jobs, and health,” Rustin argued, “every plan for the schools will fall on its face. No piecemeal strategy can work.”24

Accordingly, educator Robert J. Havighurst emphasized how “this crisis requires the active participation of schools and making and implementing policy for social urban renewal. This big-city crisis is reflected in feelings of uncertainty and anxiety on the part of parents and citizens.”25 Community schools, Havighurst reported, have made attempts to respond to the crisis by involving the various constituencies in decisions about school policy and practice to foster the links to the community.

Education is embodied in built environments and in the various groups and clients it hosts, employs, and trains, from students and parents to teachers, administration, municipal governments, urban developers, architects, and educators. Drawing on education as a palliative, order- and equality-inspiring institution had become a default mode of crisis management on a national and local scale by the 1960s. The programming of space and behavior through architecture, design, and technology was meant to remedy the obvious lack of political tools to organize public debate and negotiation—that is, of democratic governance.

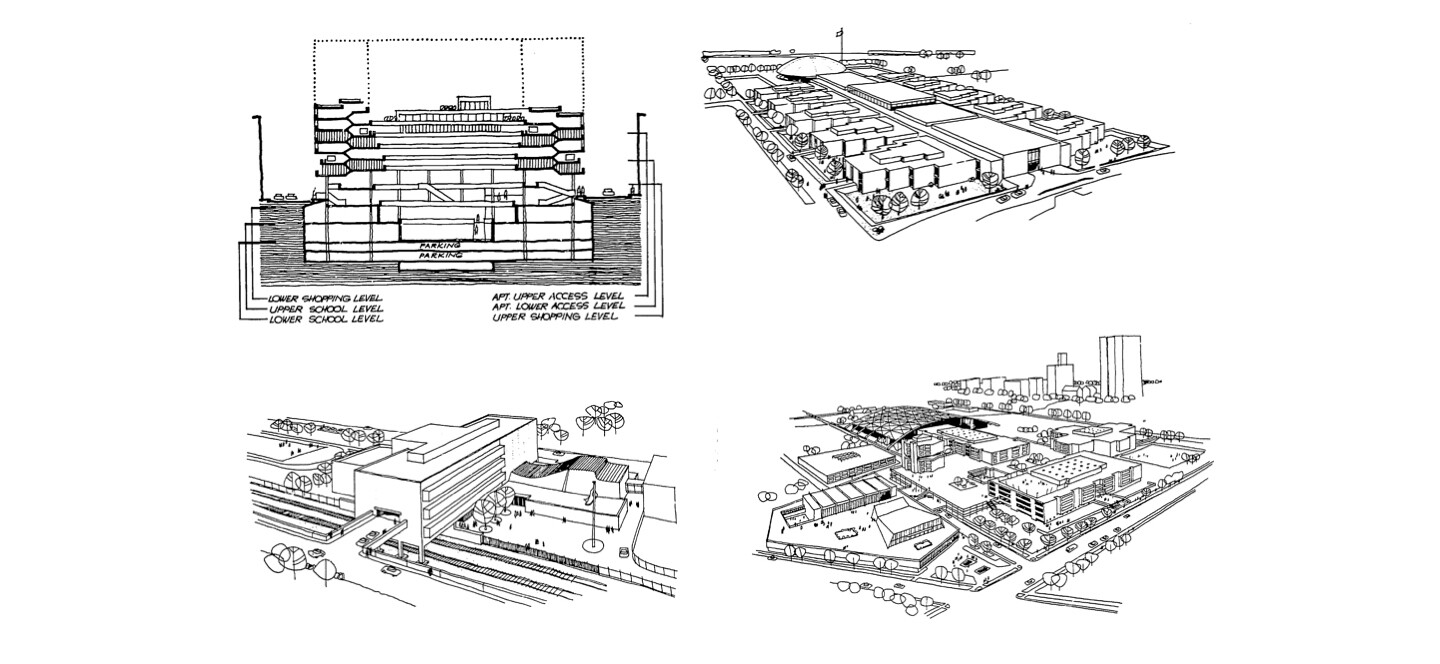

Proposals for large-scale community schools and education parks by Quinlivan Pierik & Krause/Architects; Emil A. Schmidlin, Architects; and Kiff, Voss & Franklin, Architects, commissioned and published by the Educational Facilities Laboratories prior to 1967.

Prior to the publication of the Toffler anthology, the Educational Facilities Laboratories published a small report on the school-city problem, showing a selection of architectural designs for large-scale community schools and education parks.26 These and many more designs produced in this age of rapid educational expansion formed the backdrop of the 1967 Rice Design Fete explorations. It was from there that the architects and their associated teams of educators and designers tried to make sense of the agreed-upon task of educationalizing the city through reprogramming urban space. To “involve” themselves with the social crisis produced by anti-black urban and educational politics would have been too much of a distraction from their core professional agenda of working the brains of administrations and planning committees. However, it is remarkable how their lack of interest in (or insight into) the stratified and segregated social realities of US cities constituted a common attitude across all projects at the 1967 Rice Design Fete (with the slight exception of the Vreeland group’s proposal). As “progressive” as their designs may have appeared in the eyes of the architectural and educational community and their potential clients, their lack of political traction utterly failed the scale and the urgency of the problems at hand.

The self-critical transgression of traditional architectural languages and its engagement with educational theory and practice at the 1967 Rice Design Fete showed what an assembly of white, male, Western architects was capable of in terms of progressive thinking and doing at the time and in an academic setting. Still, the blind spots of the Design Fete’s results are conspicuous, considering the ubiquity of anti-black violence, epistemic and otherwise, in the public sphere and mass media of 1960s America. Some determination must have been required to turn away from these realities, particularly when asked to conceive design solutions for “new towns,” themselves epitomes of white flight and racial divide.

One may wonder if the task of designing educational facilities muted such concerns. Presumably benevolent to the core, the very envisioning of future learning environments might have lured the participants of the Rice charrette into a fallacious post-urban-crisis, if not post-race state of mind. Why didn’t anyone feel the need to refer to the traumatizing experiences and memories of school and academia? Maybe recalling one’s own individual suffering in the institutional spaces of education could have instilled some empathy, if not solidarity with those being schooled beyond the color line.

This said, so many of the results from the Design Fete appear utterly contemporary and adventurous compared to the majority of contemporary educational buildings that still have yet to transcend rather traditional conceptions of the spatial conditions of learning. As “digital” as today’s classroom might become, the compulsory presence, often for the entire day, in a built environment known as school, is testament to a key threshold still to be surpassed. The 1967 projects therefore might still prove inspirational, regardless of their blind spots.

Cedric Price, “Learning,” Architectural Design (May 1968): 207.

“The School Scene: Change and More Change,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 130.

See Educational Research: the Educationalization of Social Problems, ed. Paul Smeyers and Marc Depaepe (Dordrecht: Springer, 2008).

“The School Scene: Change and More Change,” 130.

A kind of marathon or “all-nighter” drawing session common in architectural schools, but also, at the time, a popular form of organizing community participation in the planning process. On the charrette format, see Daniel Willis, “Are Charrettes Old School?,” Harvard Design Magazine 33 (2010), ➝.

On the EFL, see Judy Marks, “A History of Educational Facilities Laboratories (EFL),” National Clearinghouse for Educational Facilities, Washington, DC, 2009, ➝ and Amy F. Ogata, “Educational Facilities Laboratories: Debating and Designing the Postwar American Schoolhouse,” in Designing Schools. Space, Place, and Pedagogy, ed. Kate Darian-Smith and Julie Willis (London and New York: Routledge, 2017), 55–67. On SCSD, see Joshua D. Lee, Flexibility and Design. Learning from the School Construction Systems Development (SCSD) Project (New York and London: Routledge, 2018).

See Kathy Velikov, “Tuning Up the City. Cedric Price’s Detroit Think Grid,” Journal of Architectural Education 69, no. 1 (2015): 40–52, here 41–42 (I am indebted to Velikov’s research, especially for her reconstruction of the context of Price’s contribution to the Rice Design Fete and the role that Canfield and Tirrell played in it).

Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 201.

John E. Tirrell, Albert A. Canfield, “Goodbye to the Classroom,” Architectural Design (May 1968): 225

Ibid.

Educational Facilities Laboratories, “Foreword,” in New Schools for New Towns, ed. William Cannady, School of Architecture, Rice University, Houston, and Educational Facilities Laboratories (Houston: self-published, 1967), 5.

“New Schools in New Towns. The Future,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 201.

“University Sire Town,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 205.

Ibid., 205.

“New Town in an Old Site,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 211-212.

See Miriam Wasserman, “Busing as a ‘Cover Issue’—a Radical View,” Urban Review 6, no. 1 (September-October 1972): 6–11; George W. Gaston Jr., “Busing: Excuse or Challenge?,” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 46, no. 7 (1972): 434–439; Busing U.S.A., ed. Nicolaus Mills (New York and London: Teachers College, Columbia University, 1979.

“New Town in an Old Site,” 212.

“Total Learning Environment with a Kit of Parts,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 208. As Kathy Velikov has pointed out, the Rice Design Fete provided Price with the right kind of brainstorm environment allowing him to further develop ideas from the Potteries Thinkbelt project, emphasizing automotive movement and processes of urban decay as facts to be acknowledged in designing a pervasive and expansive notion of urban education or, rather, educational urbanism (Velikov, “Tuning Up the City,” 41–43).

Cedric Price, “ATOM. Design for New Learning in a New Town,” Architectural Design (May 1968): 233.

Price, “ATOM. Design for New Learning in a New Town,” 232.

“Pop Education,” Progressive Architecture (April 1968): 207.

New Schools for New Towns, 54.

Bayard Rustin, “The Mind of the Black Militant,” in The Schoolhouse in the City, ed. Alvin Toffler (New York et al.: Praeger, 1968), 29, 31.

Ibid., 34.

Ibid., 54. Robert J. Havighurst, “Differing Needs for Social Renewal.”

For an instructive study on the education parks of the 1960s see Patrick R. Potyondy, “Reimagining Urban Education Civil Rights, Educational Parks, and the Limits of Reform,” Counterpoints 461 (2014): 27–54.

Architectures of Education is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, Kingston University, and e-flux Architecture, and a cross-publication with The Contemporary Journal.

Category

Subject

This contribution derives from a presentation given at Nottingham Contemporary on November 8, 2019. A video recording of the presentation is available here.

Architectures of Education is a collaboration between Nottingham Contemporary, Kingston University, and e-flux Architecture, and a cross-publication with The Contemporary Journal.