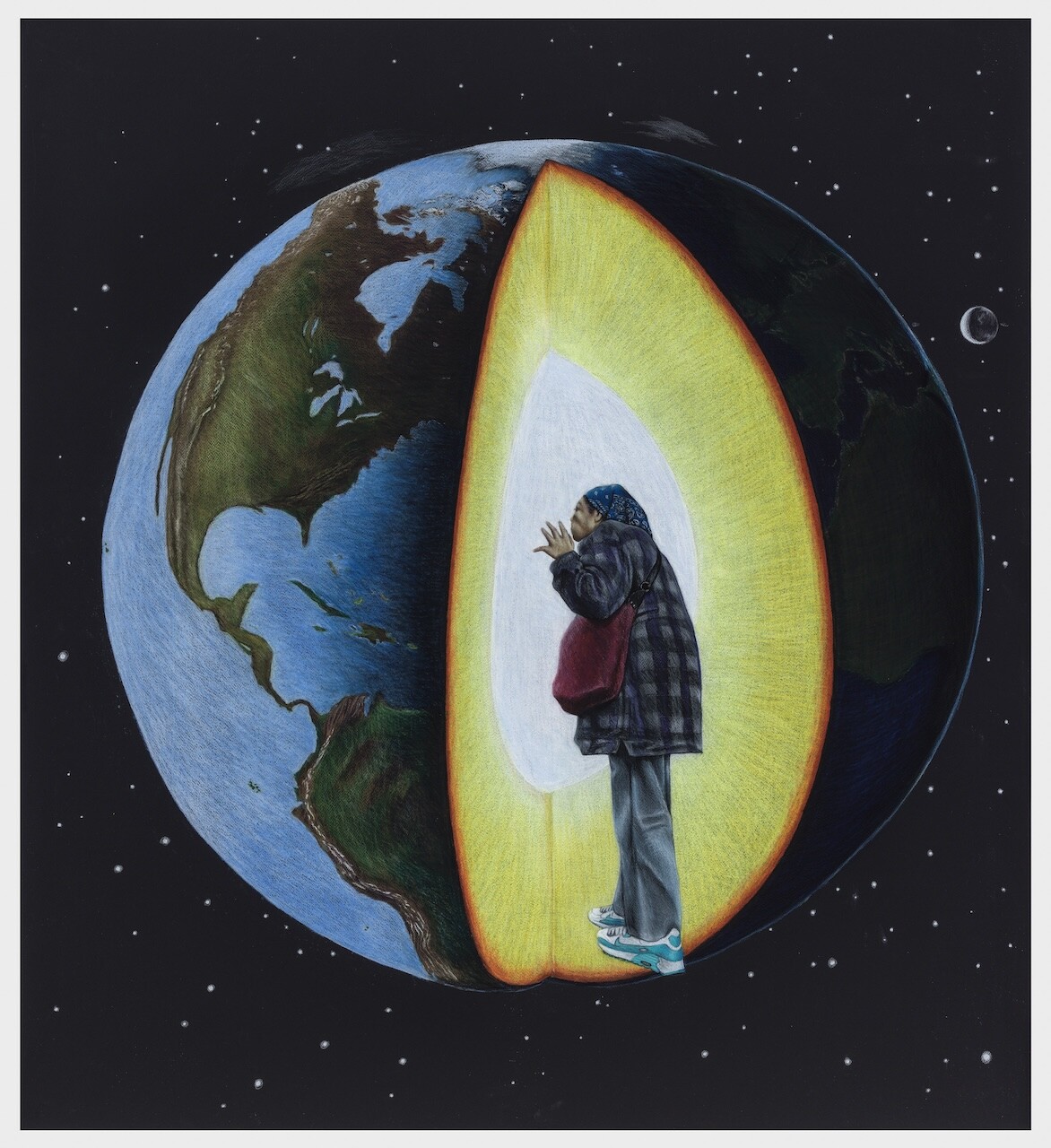

Where the Wind Meets the Water

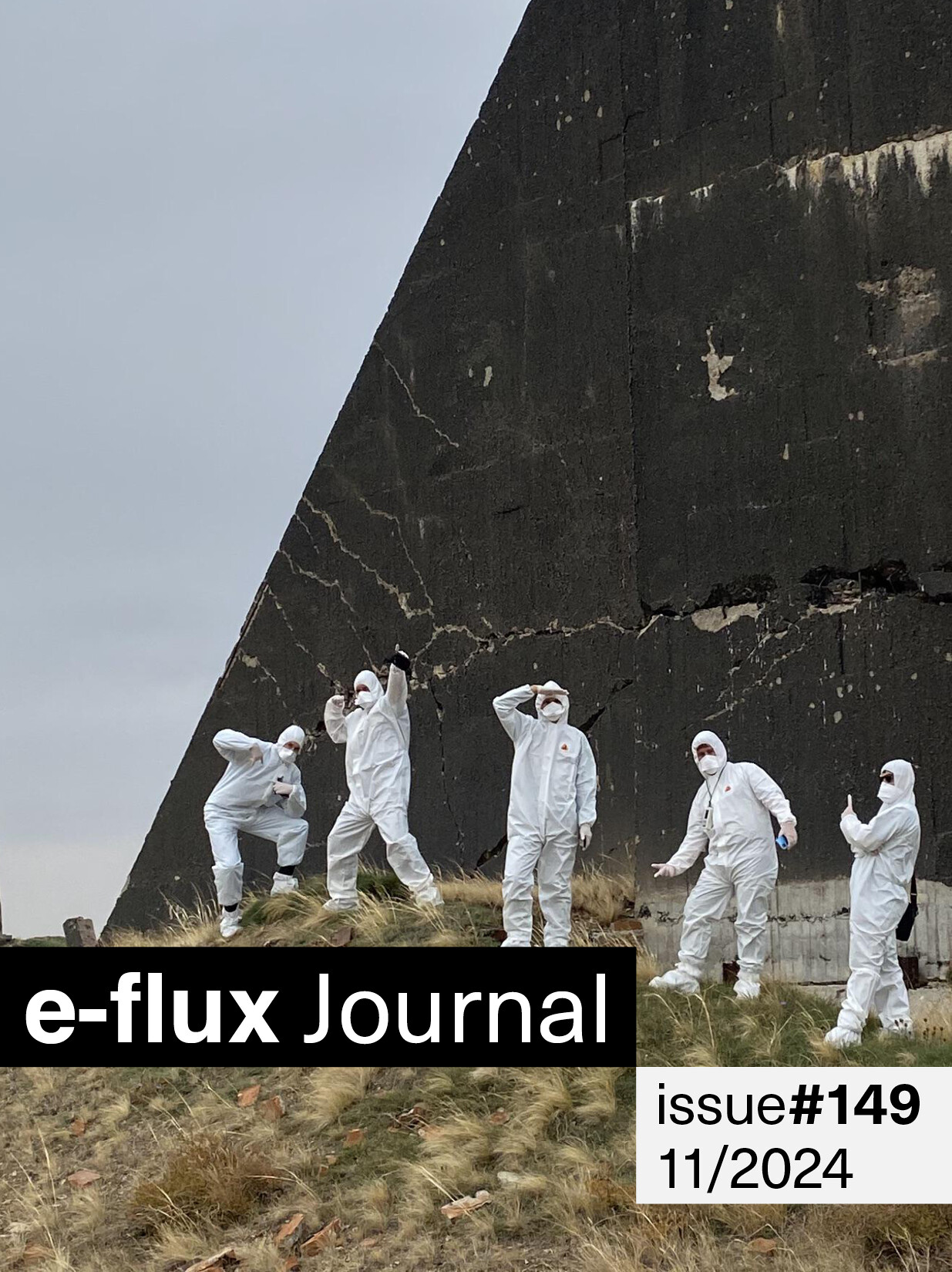

This overview of the past five years of Bassem Saad’s “world-historical” practice engages with different forms of mourning the victims of “the American Century.” The term, coined by Henry Luce in 1941 and which the Marxist scholar David Harvey has argued “disguised the territoriality of empire in the conceptual fog of a ‘century’,” finds its antidote here: Saad’s latest exhibition is grounded in events, people, and sites, merging documentary history with acid aesthetics and revolutionary zeal.

It is relevant to Ligon’s nuanced but pervasive intervention that the museum was founded in 1816 when Viscount Richard Fitzwilliam left his collection of art and cultural artifacts to the University of Cambridge with a bequest to construct a museum of art and antiquities. This leaves it with twinned affiliation: both to an esteemed educational institution and to a landowner whose fortune derived in part from his grandfather’s investment in the transatlantic slave trade.

Barely twenty-four hours after it was declared that Georgia’s parliamentary elections had been won by Georgian Dream, the country’s president, Salome Zourabichvili, denounced a “total falsification” of the vote and called on her fellow citizens to protest. It feels apt, therefore, that artistic directors Tinatin Gurgenidze, Otar Nemsadze, and Gigi Shukakidze should have chosen the theme of “Correct Mistakes” for the fourth Tbilisi Architecture Biennial, with its multiple meanings, from useful errors to their possible rectification.

Unlike the Muybridge images, which assert control, surveillance, and dominance over Modoc territories, Piron portrays the landscape as unattainable, allowing it to tell its own story of resistance. His filmmaking process becomes forensic research: it challenges the historical misinformation in the photographs through geographical evidence. Following the rise of fake news, contemporary cinema has seen a shift towards forensics—see the works of Forensic Architecture, Larissa Sansour, the New Red Order and, even earlier, Walid Raad. These projects interrogate images and historical narratives to visualize human rights abuses and claim justice.

The show is surprisingly simple, with four works across four rooms: alongside The Hearth is The Wheel (a chandelier-like structure surrounded by music stands holding songbooks); The Oratory (where visitors are encouraged to sing into a microphone, triggering an AI model to harmonize in response, in front of another altar-like object); and, reverberating around the edges of the gallery space, a series of ethereal musical compositions called “Linked Diffusion.”

The deep boom of a subwoofer meets you on the stairs to the small gallery. Inside, a two-channel video projected across opposite walls shows barren landscapes with figures moving through them, close-ups of plants and foliage, and more besides, the imagery by turns sped up, slowed down, color-adjusted, and layered. One half is framed to the dimensions of the space; the second is projected at an angle, so the pictures invade the ceiling and floor. It is a hypnotic, unnerving assemblage.

Collective Comfort