The exhibition’s chief draw is Murni, whose works, executed in her signature style of flat, simple forms in bold outlines and bright colors, operate in the register of the squalid-sacred: dicks, vaginas, breasts, high heels and sharp nails in all manner of hybridizations, permutations, and penetrations. Sexuality can be pain or pleasure, weakness or empowerment, sordid or spiritual.

If there was one exhibition that tapped into the Tunisian zeitgeist during Jaou, the contemporary art biennial organised in Tunis by the Kamel Lazaar Foundation, it was “Hopeless.” Curated by Chiraz Mosbah on the grounds of Club Aviron Tunisois, with storehouses for kayaking and rowing perched on the edge of the water, the show references a desire among many young Tunisians to leave the county, given its struggling economy and increasing authoritarianism, and its position as a crucial crossing point for clandestine migrants.

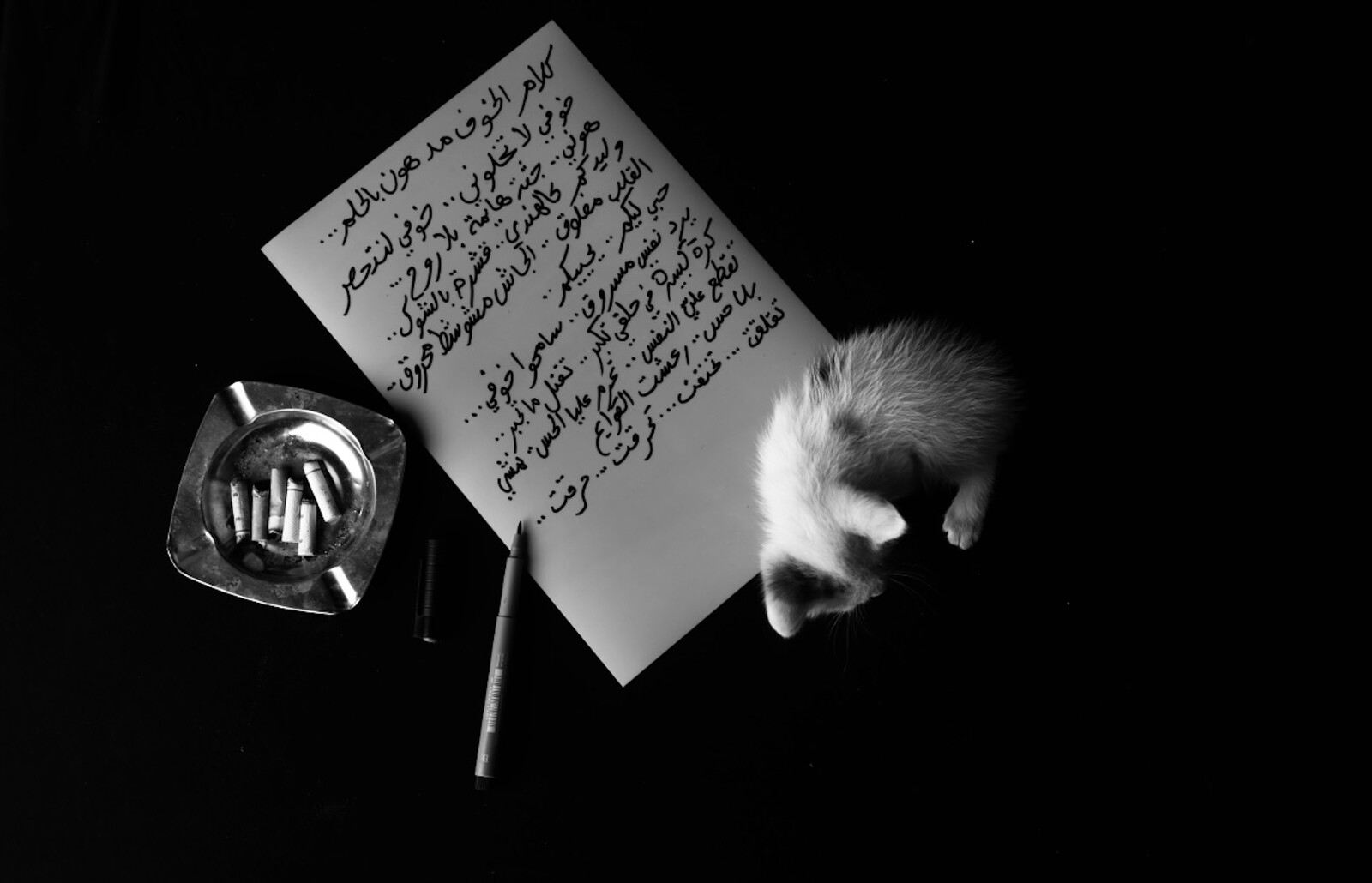

Photography has allowed Abdouni to excavate, reinvent, and remember queer histories in Arab cultures. Here he shifts view to his home region of Beqaa, Lebanon. In pulling apart family photo albums, subjecting them to the scrutiny of his loving but unsentimental gaze, the artist returns to his childhood navigations within the complex cultural norms of a heterosexual masculinity and male camaraderie that embody Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s theory of “male homosocial desire” grounded in anti-queerness.

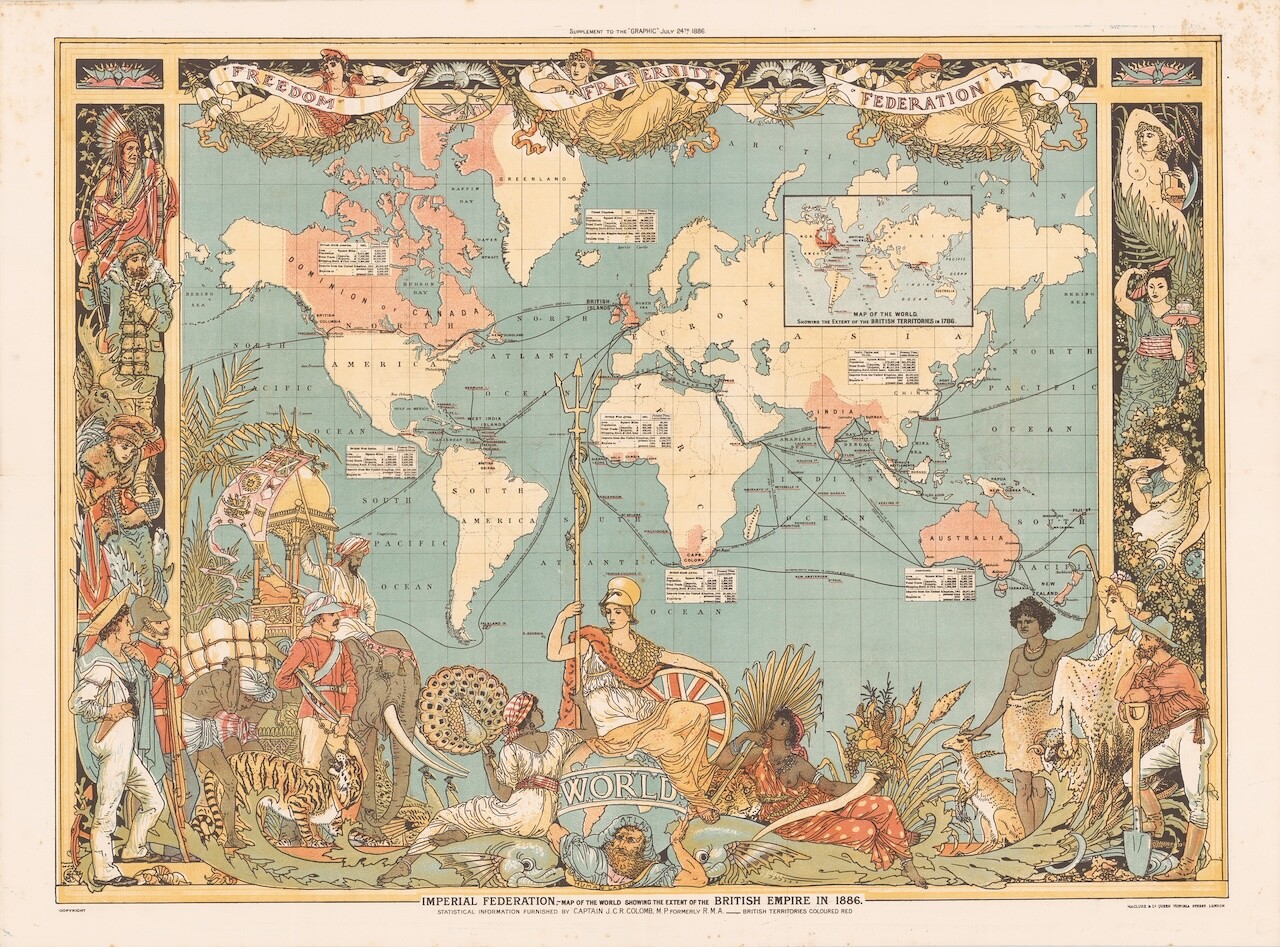

Alÿs built his project around the Strait of Gibraltar, which is one of the most visible hinges between the Global North and Global South. In ongoing, so-called “postcolonial” forms of resource extraction, multinational corporations and debt service payments, alongside internal state corruption and dysfunction, funnel wealth out of African countries, thereby helping to propel the tide pushing workers and families toward Europe and the United States.

Like many recent exhibitions of a similar size, “Mil Graus” presents a mix of recurring themes that can feel unmanageable. It’s as if the inclusion of concepts ranging from ecology and the post-Anthropocene world to colonization, queerness, identity, ritualism, or the sometimes-disconcerting mix of the esoteric and the political, all melted into the same pot, were a mandatory bureaucratic requirement.

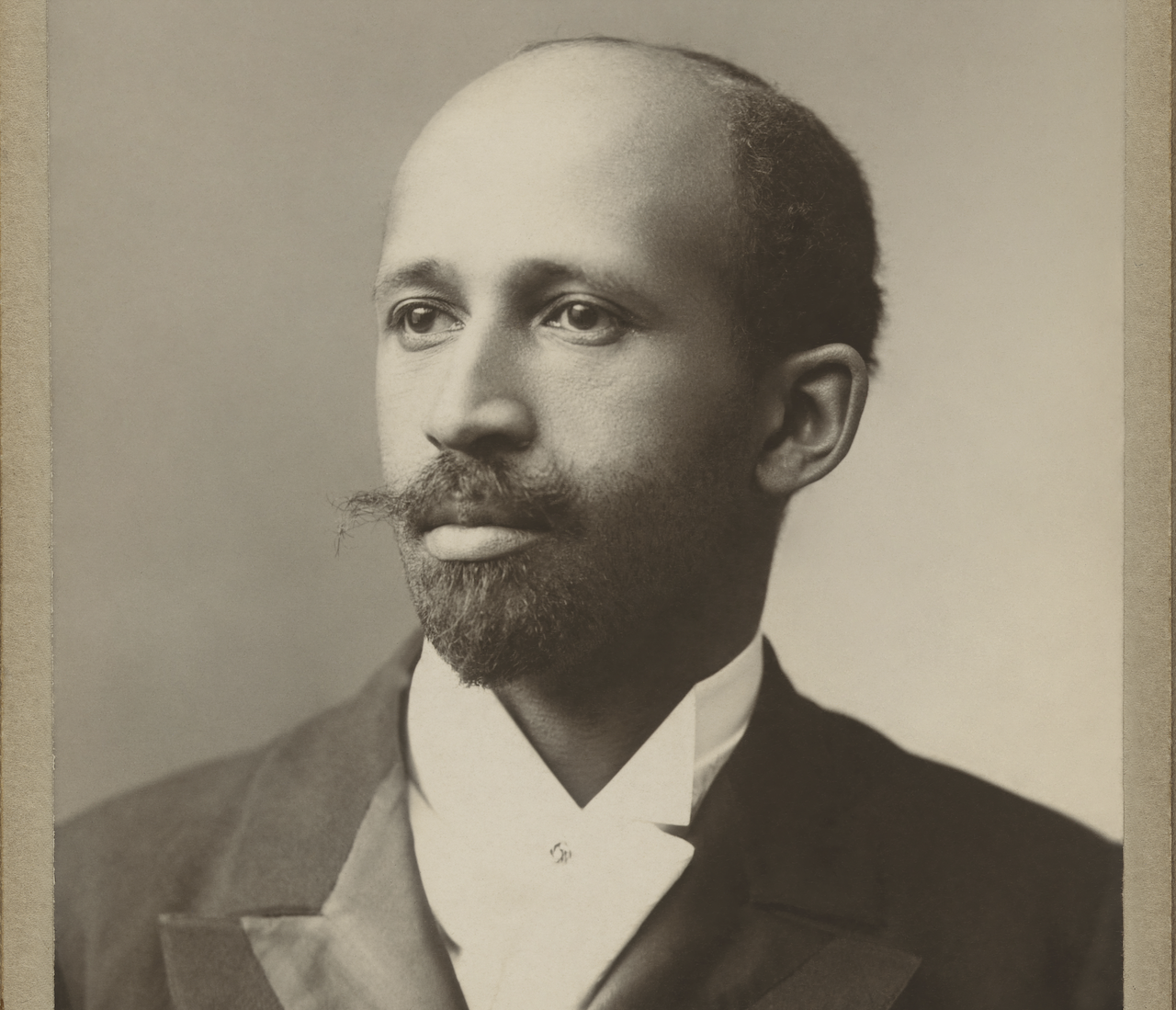

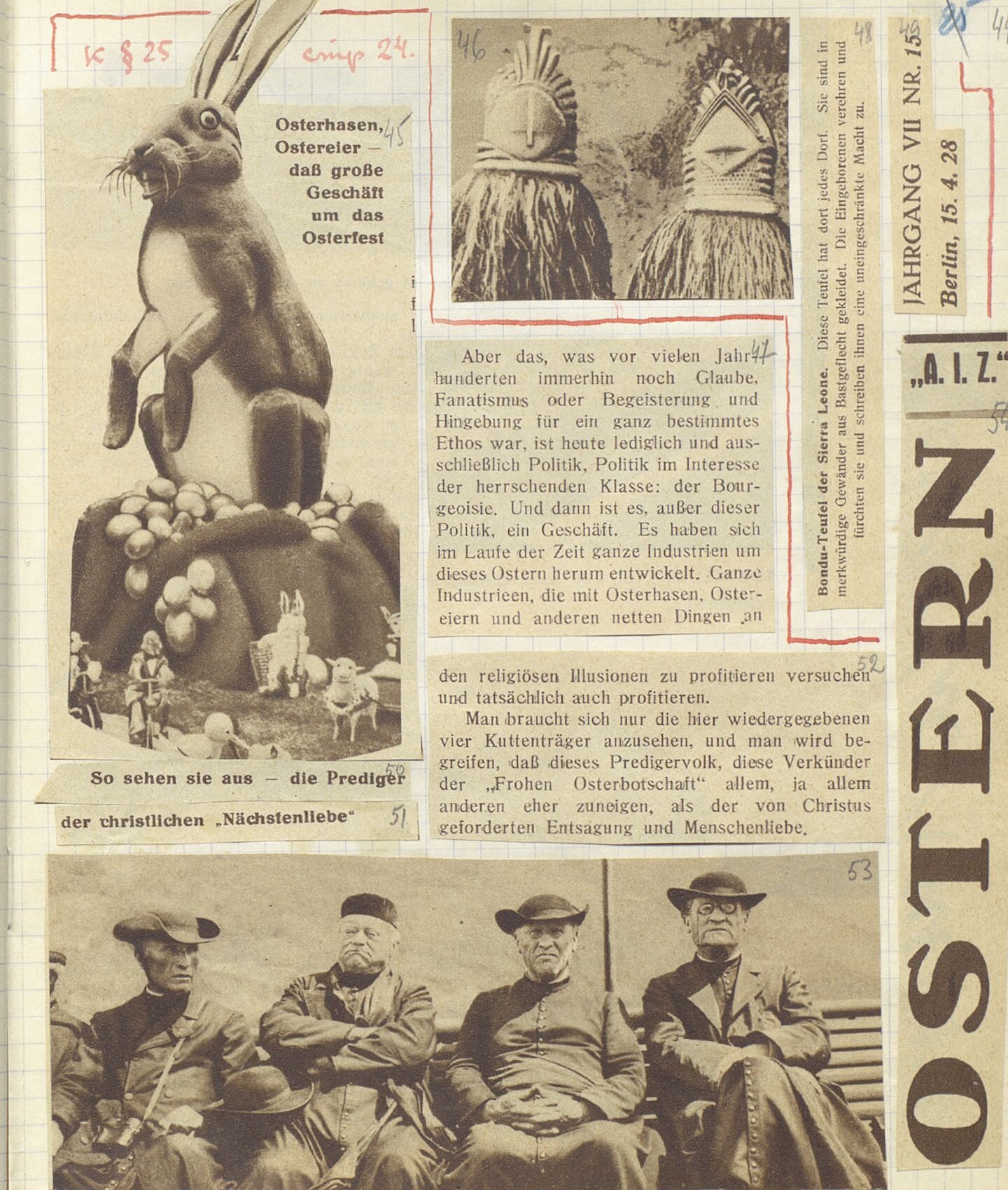

Jalal critiques the ways in which perceptions of value are propagated through print and visual culture. Here, the artist positions the fleeting acquisition of social status as a Pyrrhic victory whose cost is violence and destruction. In a small untitled collage made on a Cadillac owner’s manual, we see sheets of silver leaf pressed around the embossed logo of the luxury vehicle, a signifier of upward mobility, particularly in Black communities (Cadillac was among the first car companies to sell to African Americans in the 1930s).

The City May Now Scatter