Are You a Living Thing That Is Dying or a Dying Thing That Is Living?

Art institutions have thus become refuges for activities outside the traditional remits of the arts and humanities. That museums are now expected to serve an educational function—that their public funding is often made dependent upon this—might be understood as a function of the managed (which is to say politicized) decline in funding for state education (so that creative workers are now expected to pick up the slack). Likewise, talk of transforming museums into spaces of “healing” and “care” begs the question of why our governments are not purpose-building new institutions dedicated to those values.

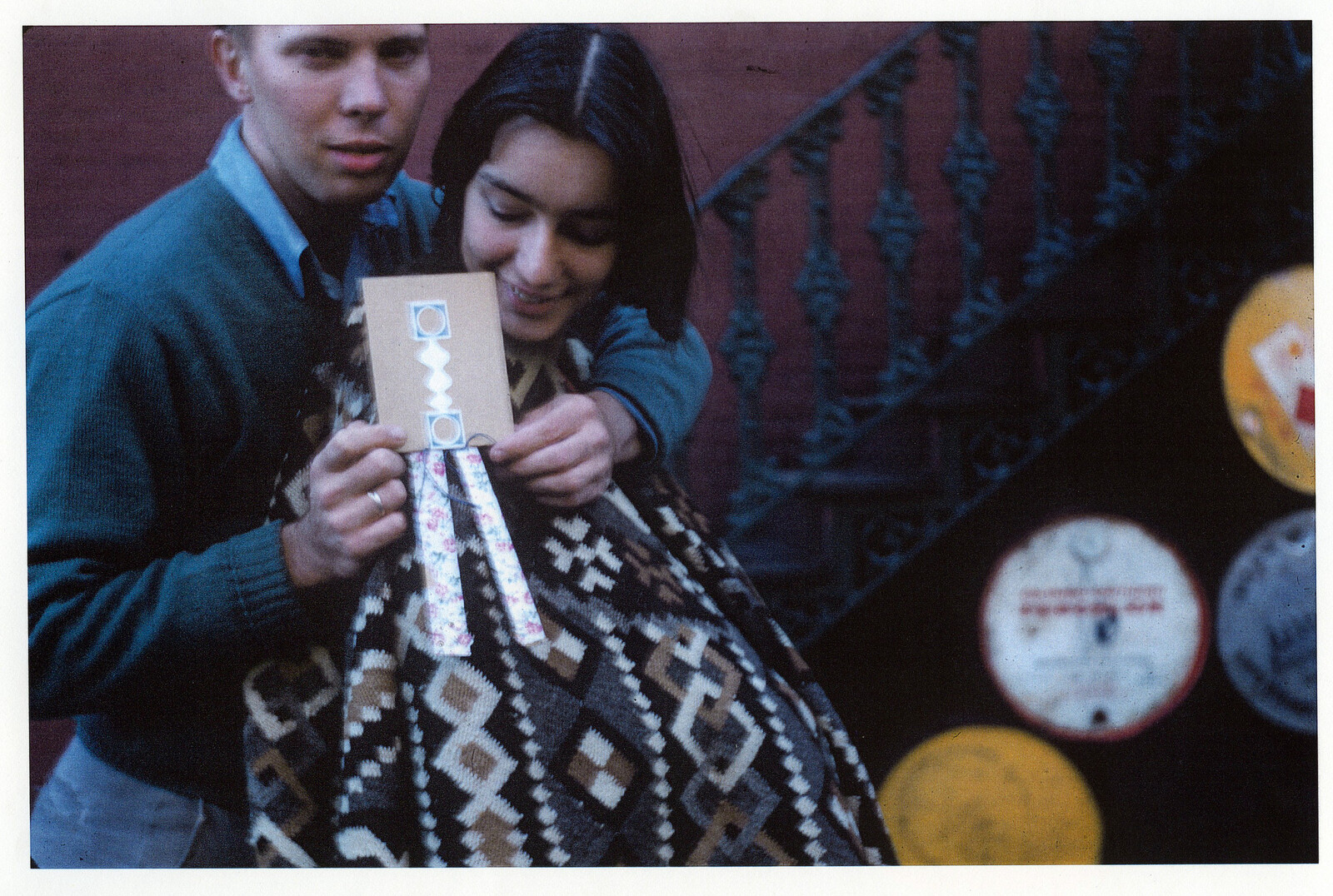

Johnson reveled in chance, in jokes, in surprise, in disappearance. He evaded personal questions, and preferred his work to be discovered by serendipity than by design: perhaps by bumping into him on the street with a box of collages under one arm, or receiving a grubby envelope through the post, name Sharpied under the line “Please send to.” Ellen Levy’s A Book about Ray—in her words, less a “life story” than an “art story”— takes its cue from Johnson’s intuitive way of working, unfolding through association instead of strict chronology. The approach is ideally fitted to her subject.

Sagarika Sundaram and I both had modest period-marking ceremonies, in India and Sri Lanka respectively, when we first started menstruating. Such rite-of-passage ceremonies are passed on from generation to generation in South Asian communities across the globe. Their regional differences—demonstrated in her Chennai-based ceremony and mine in Colombo—dominated my first conversation with Sundaram, whose art practice draws on such re-evaluations of her South Indian background, among other subjects.

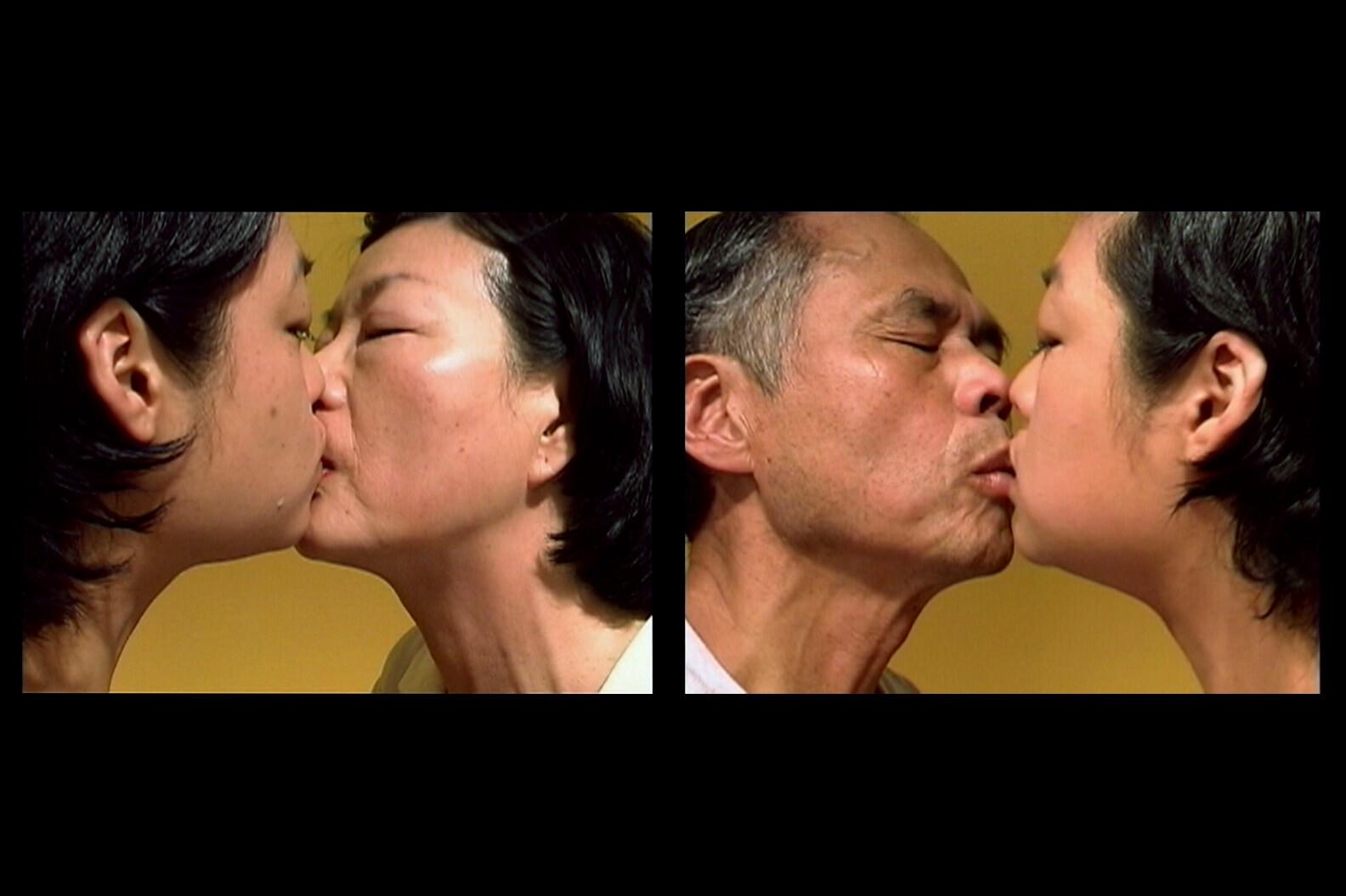

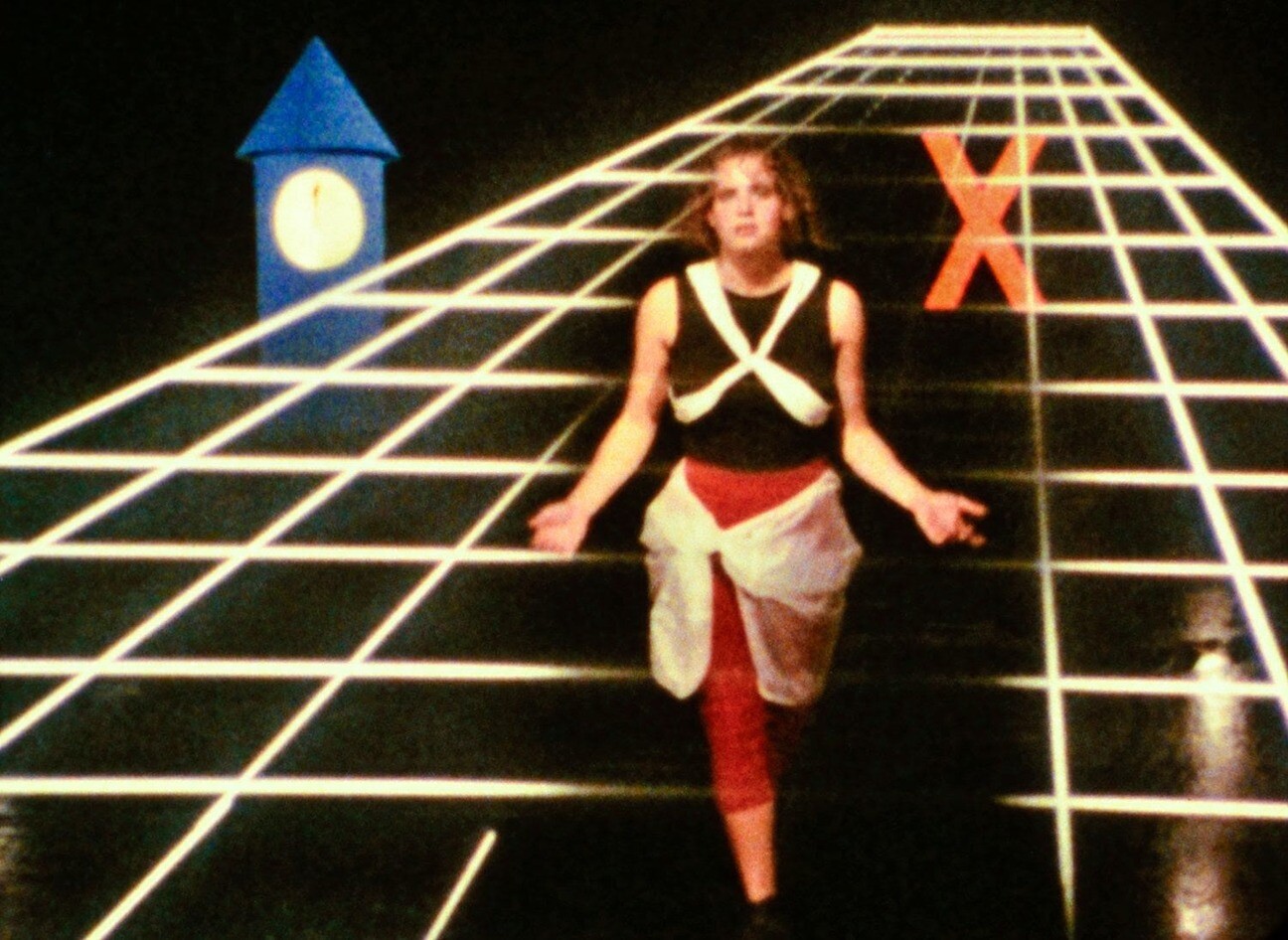

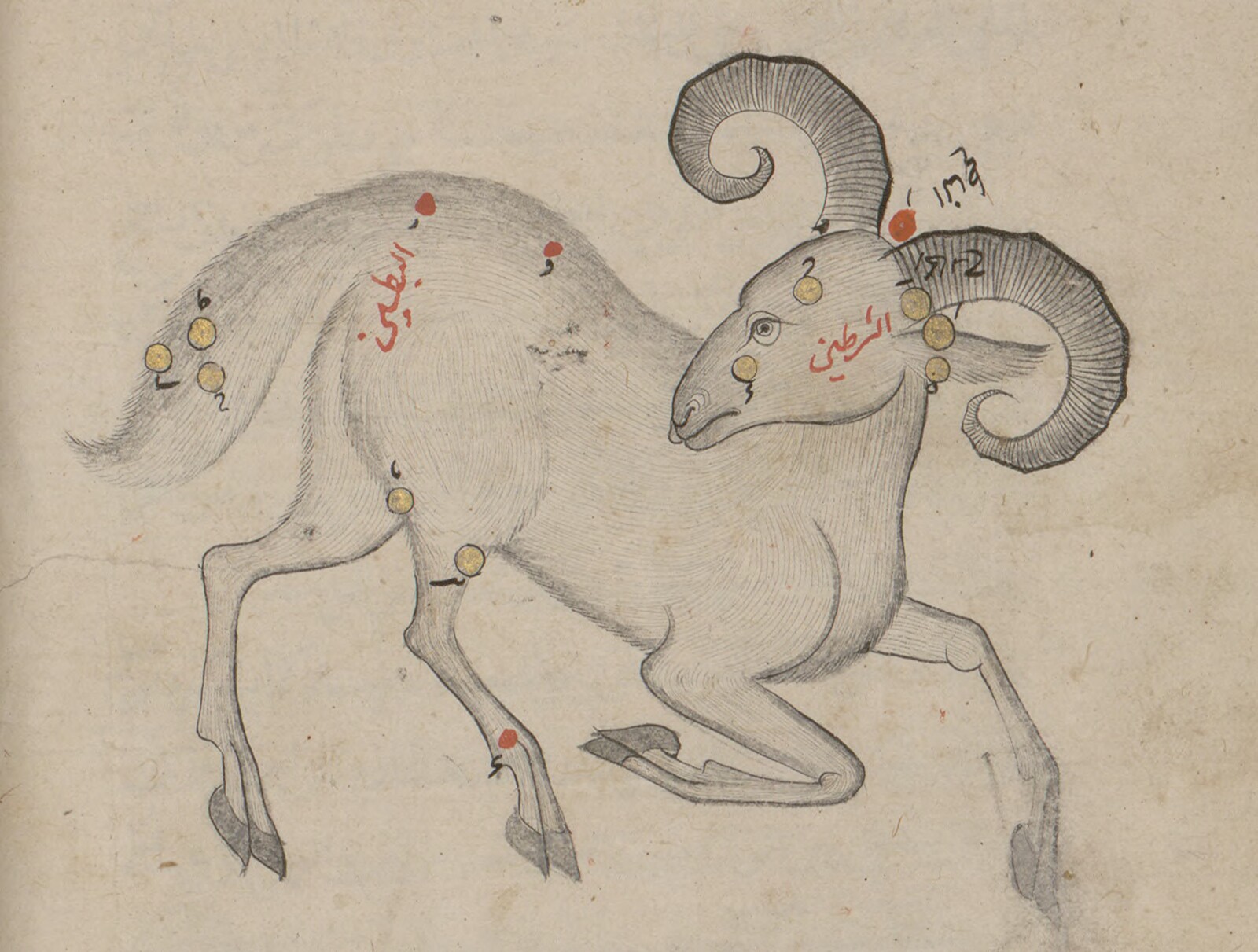

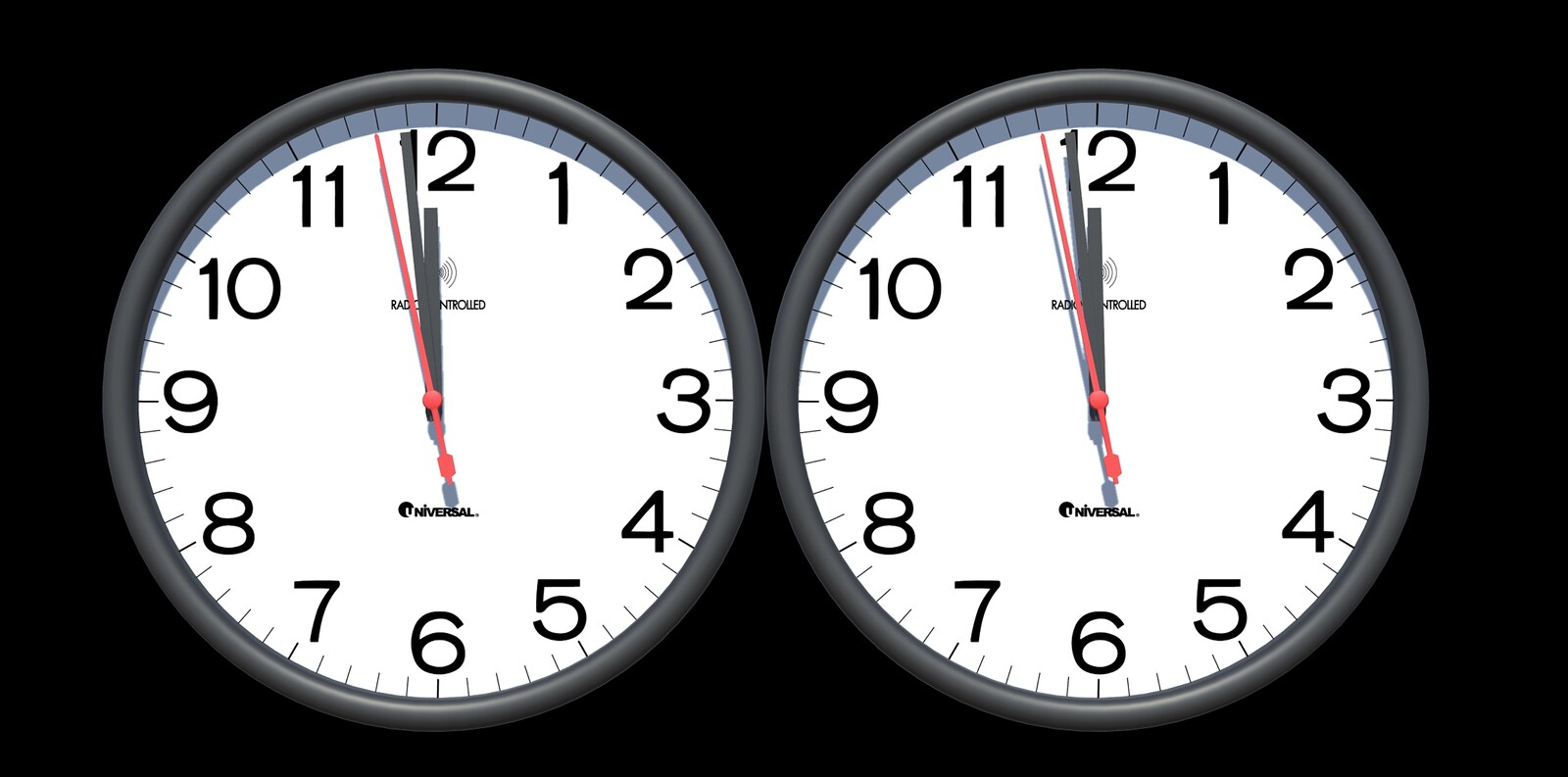

Ho Tzu Nyen has long been preoccupied with the way history repeats in disguise: empire folds into empire, technologies of governance advance, and yet the conditions of control remain eerily familiar. In the Luxembourg iteration of the Singaporean artist and filmmaker’s mid-career retrospective, time is an instrument of power that measures mechanical precision against mythological recurrence: Ho’s work asks what it means to resist its rhythm.

A storm is raging in Singapore. Waves break against park benches and dash against trees. Public housing estates are half-submerged; bobbing on the water surface are abandoned lifeboats and jackets. With Disaster-free (2024), featuring footage generated with the help of AI, artist Ong Kian Peng has created a Singaporean disaster movie, in which rising sea levels have transformed the developed island-state into a gray, glimmering water world that we scan through the eyes of a single survivor paddling around in a kayak.

It’s fair to say that artists aren’t going to save the world. But this exhibition at C3A proceeds from the limited if hopeful assumption that they might be able to make a difference. “Ecologies of Peace” emerged from a series of partnerships between TBA21 and underfunded regional institutions, and at first glance, its title shares a sunny vagueness familiar from biennials in other parts of the world. Curated by Daniela Zyman, it claims to focus on “practices of mourning and forgiveness,” though, for the most part, it illustrates the scale of the devastation that calls for them.

As the shortlisted artists and curators for the Australian Pavillion at the 2026 Venice Biennale, we are writing in support of the winning team; Khaled Sabsabi (artist) and Michael Dagostino (curator), selected by industry led experts through a rigorous and professionally independent open-call process.